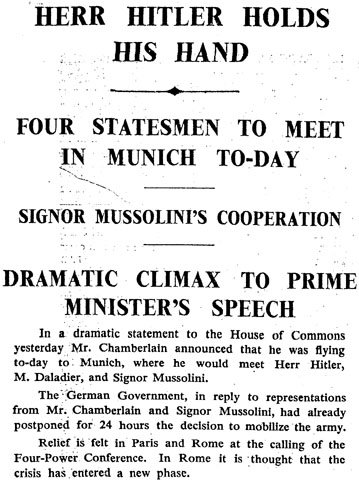

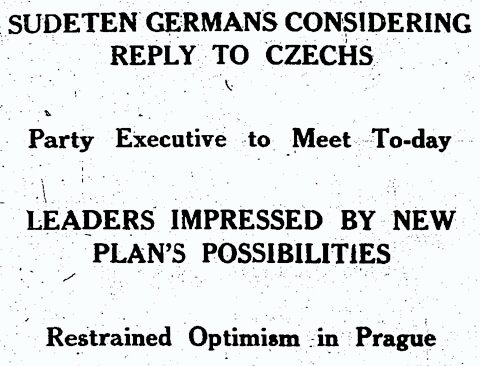

Chamberlain is meeting Hitler at Godesberg today (the headlines are from the Manchester Guardian, p. 11). The good news (for Chamberlain, anyway) is that the Czechoslovakian government has finally, and very reluctantly, accepted the Anglo-French plan for the transfer of German-majority areas to Germany. (Which, it seems, still hasn't been officially published.) That would mean that Hitler would get what he wants without war, which is what Chamberlain is trying to avoid. The bad news is that it's now clear that Poland and Hungary are lining up for their own pieces of Czechoslovakia: the German press is referring to a 'united front' of Germans, Poles and Hungarians. And the Anglo-French plan doesn't provide for this at all. As The Times notes (p. 10):

Czechoslovakia is faced with the loss in the near future of Western Bohemia, Northern Bohemia, German Silesia, Polish Silesia, and the Hungarian Parts in the south.

Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet Foreign Minister, has announced at the League of Nations Assembly that the Soviet Union will give Czechoslovakia 'immediate and effective assistance' under the terms of the Soviet-Czech pact, providing France (Czechoslovkia's other ally) does the same. But he criticised the Anglo-French plan as 'a capitulation which was bound sooner or later to have quite catastrophic and disastrous consequences' (The Times, p. 10).

To add insult to injury, there's a growing chorus of disapproval of the plan, at home and abroad. According to a leader in the Manchester Guardian (p. 10), `A week ago Mr. Chamberlain has the admiration and trust of the world.' But:

If Mr. Chamberlain reads his papers to-day as he flies once again to Germany he will see no trace of admiration for his part as the head of a great democracy, no trust that he can save any shred of principle from the wreck, no belief even that he can recover his country's honour.

Prominent political figures are lining up to criticise Chamberlain, including some from his own side (though, as yet, the ministerial ranks are holding firm), as several articles in The Times show (p. 15). Sir Archibald Sinclair, leader of the Liberals said in a speech at the National Liberal Club that Britain's 'submission' to Hitler's demands is simply due to 'threat of war'. Anthony Eden, who was Chamberlain's Foreign Secretary until he resigned in February over relations with Italy, spoke at the Stratford-on-Avon branch of the English-speaking Union (and on the wireless in America too). He did not attack appeasement as such:

But if appeasement is to mean what it says, it must not be at the expense of either our vital interests, or of our national reputation, or of our sense of fair dealing.

Don't be deluded that appeasement is preserving peace: 'each recurrent crisis brings us closer to war; we slither ever closer to the abyss'. And Winston Churchill, a prominent backbench MP, in a statement (press release?) to the Press Association, warned of 'the disaster into which we are being led'.

The neutralization of Czechoslovakia alone means the liberation of 25 German divisions to threaten the Western Front. The path to the Black Sea will be laid wide open to triumphant Nazism.

This menaces 'the cause of freedom and democracy in every country'. And because German 'war power' will grow faster than British or French 'preparations for defence', he implies that the time for war is now.

It's hard to define precisely, but my impression is that the tone of the press coverage of the crisis has become more desperate in the last few days. Panic is definitely too strong a word, but the anxiety level is certainly rising rapidly. Fully 10 of the 20 pages in today's Manchester Guardian are wholly or partly given over to the crisis, or to the air raid precautions (ARP) which are now assuming such urgency because of it. (Though the following picture of a sign at the Blackpool illuminations, from the Manchester Guardian, p. 9, would have been planned well before the current unpleasantness. That's the local war memorial beside it, by the way.)

On the one hand, there are those who favour some form of compulsion in order to force people to undertake ARP. Sir Edward Grigg, a Conservative MP, spoke at the luncheon of the Altrincham Show (!) on the need to organise the civilian population for air attack, in part through a form of national service (The Times, p. 15). Surgeon-Commander G. Ernest MacLeod (RN, retd.) writes to the Daily Mail (p. 10) to ask

If people refuse to take precautions after the reasons for doing so have been explained should not the Home Office step in and make it a penal offence not to do so?

Others try scaremongering: James Wilson, the Chief Constable of Cardiff, complains about a shortfall of nearly 3000 ARP wardens, out of 4200 needed (Manchester Guardian, p. 4):

I ask the public to visualise the indescribable chaos and panic which would exist in this city in the event of a raid simply through their failure to play unselfishly to play unselfishly their part in the scheme in good time.

He's got plainclothesman out door-knocking, looking for volunteers. Professor J. B. S. Haldane, a biologist and a socialist, has also been talking to the people, in the form of the thousand employees of Messrs. L. Gardner and Sons' oil engine works in Salford (Manchester Guardian, p. 13). He explained his system of deep shelters to them, which would cost about £500 million. 'That is a lot of money, but I would sooner know that my skin was safe than know that foreigners were being bombed in their countries for my defence.' (Of course, deep shelters couldn't be built in time to be of use should the current crisis turn into a war, and Haldane didn't suggest that they could.) Lastly, there's a touching letter in The Times (p. 6), signed 'THREE YOUNG FATHERS'. They complain about a 'Handbook of A.R.P. Instructions for Householders' which the Home Office drew up over a year ago and then never distributed (except to ARP volunteers). And despite the crisis, it still hasn't been distributed. And yet people who ask their local ARP authorities for advice are being referred to this handbook.

In time of emergency it is quite fantastic to assume that air raid wardens will have the time to interview personally each inhabitant of their zones. But without such visits or the publication of the handbook the ordinary householder is left ignorant and worried. It is surely realized in official quarters that young parents are unable to help as A.R.P. volunteers. The men are needed elsewhere and the women have their children to look after. What, then, are young husbands and wives to do about A.R.P.?

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback:

Airminded · Friday, 23 September 1938

Pingback:

Airminded · Post-blogging the Sudeten crisis: thoughts and conclusions

Anonymous

I am most displeased with the lack of dated events in this article. I demand to know the date of the Soviet-Czech Pact under the Freedom of Information Act.

Anonymous

Grrrrr