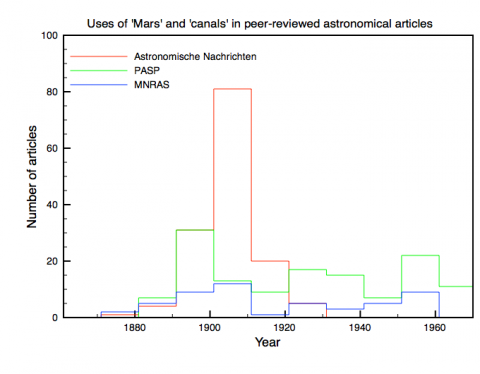

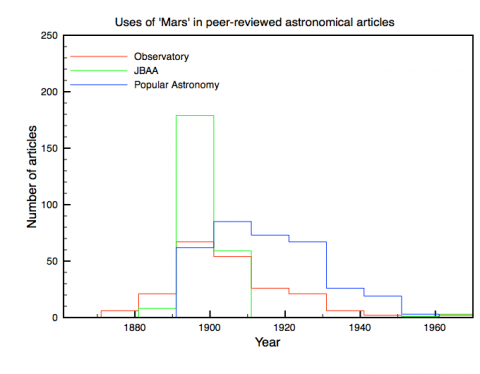

So, to wrap up this accidental series. To check whether professional astronomical journals displayed the same patterns in discussing 'Mars' and 'canals' as the more popular/amateur ones I again looked at the peak decade 1891-1900, this time selecting only the more serious, respected journals. However, because of the French problem I had to exclude L'Astronomie and Ciel et Terre (the former was apparently more popular anyway). So for my top three I ended up with Astronomische Nachrichten, Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific (PASP) and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). Astronomische Nachrichten ('astronomical notes') was the leading astronomical journal of the 19th century, founded 1821. It published articles in a number of languages including English. Fulltext Service seems to be multilingual, as it picks up the German (at least) equivalents of Mars/Martian and canal/canals. That doesn't help with the French problem, but that will only affect a small minority of Astronomische Nachrichten's articles. The Astronomical Society of the Pacific was founded in California as a joint amateur-professional organisation. Its PASP is now a very highly regarded journal, although I must admit I don't know if this was always the case. MNRAS is the journal of the Royal Astronomical Society in Britain. It also happens to be where my solitary peer-reviewed astronomy article was published (and when I say 'my', I think approximately 1 sentence relates to research I actually undertook), but even so it really is a highly-respected journal.

Astronomische Nachrichten published by far the most articles mentioning 'Mars' and 'canals'. Interestingly, this was in the 1900s, not the 1890s. The numbers decline rapidly thereafter: there were still a fair few in the 1910s, but hardly any in the 1920s and none at all after then. PASP's peak was in the 1890s, when it published exactly as many articles as Astronomische Nachrichten. There was a big fall in the 1900s, but unusually its level of interest in Martian canals, at least as measured by the number of articles mentioning 'Mars' and 'canals', stayed reasonably constant throughout the 20th century, at a bit over one a year. It must be said, however, that one article a year is not exactly indicative of an obsession. We are getting into some small numbers here. MNRAS's numbers are even smaller, though like Astronomische Nachrichten they peaked in the 1890s and then exceeded that level in the 1900s.

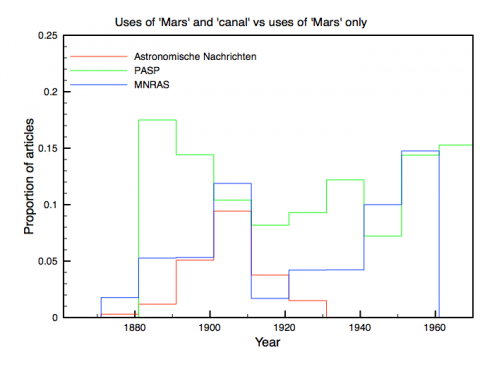

Just for completeness, here's the ratio of articles mentioning of 'Mars' and 'canals' to those mentioning 'Mars' alone. Because of the small numbers not much weight can be placed on this, but it does suggest that PASP's interest in the canals in the 20th century tracked its interest in Mars fairly closely. Also noteworthy is that Astronomische Nachrichten has peaks in both graphs in the 1900s, which is also when it published the most mentioning 'Mars' (859 in total). That is, even as the number of articles on Martian canals (yada yada) increased in absolute terms, they also increased as a proportion of the number on Mars altogether, to nearly 10%. So this is consistent with the picture of the 1900s as the peak decade for the canals controversy, not the 1890s as I had originally assumed.

The upshot of this is not a lot. I think these plots do match the patterns I found in the previous posts, but only weakly. What's really worrying is the small numbers. If these are the three professional journals which published the most articles on the Martian canals (and there may be other gaps in the ADS database), then apart from Astronomische Nachrichten in the 1890s and 1900s (and maybe in the 1910s) and PASP in the 1890s (and maybe the 1920s and 1930s) they didn't really publish very much; and, of necessity, the other professional journals published even less. So can it really be said that professional astronomers -- as opposed to amateur astronomers and for that matter the public -- as a whole were particularly interested in (let alone persuaded by) the Martian canals hypothesis? I'm not sure. Indeed, I'm not sure whether this exercise has shown anything at all, other than the need to look very carefully at your data, even when the story it is telling seems to make sense. The only way to find the answers, really, is to dig much deeper into the data, and start reading the articles themselves and put them in context: quantitative history alone isn't good enough. Which is quite reassuring, actually.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Daniel Fischer

If you run "Martian canals" through http://books.google.com/ngrams you get the same basic plot (within one second): nothing at all before the 1880s, a sharp peak around 1908 and "lingering interest" til the present, with a secondary peak around 1960. And again, there is no telling whether the respective book sections are pro or contra the existence of the canals or mere historical reviews.

Erik Lund

Sigh. I kind of liked your crazypants correspondent, Brett. At least he'd mapped out a theory where the canals could actually exist. Although there is the bit about sending the Air Force to blow up all the Martians, and killing JFK because he knew too much, which isn't quite as attractive as imagining that the Towers of Truth still stand along Mars's Grand Canal.

Just so that everyone is aware of it, I will also mention Maria K. de Lane's [i]Geographies of Mars[/i], a good start on what could easily be a much larger field of studies into the way that the imagined geographies of Mars were deployed on Earth in a cosmic history of human civilisation. There's just so much stuff there about the way that images of the "dying," canal-watered Mars served the needs of everyone from eugenicists like Lowell's brother to grand historical theorists like Wittfogel.

Brett Holman

Post authorDaniel:

Thanks. I didn't use Google's Ngram Viewer for this because I was interested in the astronomical response to the Martian canals. You can't get that from Google because there's no way to search scientific literature alone, let alone astronomical ones. That's why I was pleased to find the ADS Fulltext Service. Still, that it does turn out much the same is interesting. And perhaps expected, given that I've more or less concluded here that even in the refereed subset of ADS Fulltext Service, the signal here is dominated by popular-ish journals, whereas it's not clear at all that the more professional ones were interested.

Erik:

Well, you might have helped him out a bit then!

Thanks for that reference, I think I've seen it around but will have to pick it up now. Also, apparently Joshua Nall at Cambridge did his PhD on the public reception of the Martian canals. A long time ago (i.e. before the PhD, in fact before I started studying history formally) I did think of going into the history of the perceptions and uses of Mars myself, and these few posts are the remnants of that interest. I haven't kept up with the literature though, I'm glad to see that there's some interesting work being done on the topic.

Jon

A very good series of articles. With respect to your question:

"So can it really be said that professional astronomers — as opposed to amateur astronomers and for that matter the public — as a whole were particularly interested in (let alone persuaded by) the Martian canals hypothesis? "

The answer is clearly "no". For the most part, judging from what I have read by Patrrick Moore and Carl Sagan, most planetary astronomy between 1900 and 1960 (inlcuding lunar work) was done by amateurs. Most professional astronomers were much more interested in stellar and galactic astronomy.

Brett Holman

Post authorGlad you enjoyed them! Something a bit different for me, topic-wise.

From the way I phrased that question, yes, that's quite right. But what I actually had in mind was that part of the professional astronomical community which took an interest in (and might therefore publish on, which is the metric I'm using here) such questions, i.e. professional planetary astronomers. After all, an astronomer who has devoted their professional life to studying supernovae remnants is unlikely to publish many articles on Mars, let alone Martian canals, and quite probably would not be current in the literature.

That said, I think there was more crossover than might be thought. Astronomy was much smaller back then, and the advance of specialisation uneven. Many notable professional astronomers who are better known for their contributions to stellar and galactic astronomy did in fact do at least some planetary work. Vesto Slipher comes to mind: famous for being the first to measure the radial velocity of a galaxy, in fact he was a planetary specialist like his brother Earl (who was involved in compiling the 1962 USAF Mars map). E. E. Barnard, the great stellar astronomer after whom Barnard's Star is named, spent a great deal of time observing the planets: he made the first discovery of a Jovian moon since Galileo, for example. In the mid-20th century, the French astronomer Gérard de Vaucouleurs published his own research on Mars and organised a worldwide Mars patrol for the 1956 opposition. In fact, as I recall learning of de Vaucouleurs' interest in Mars was one of the sparks for my own interest in the present topic, because I knew him better as one of the outstanding galactic astronomers of the late 20th century, coauthor of the standard Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies, etc.

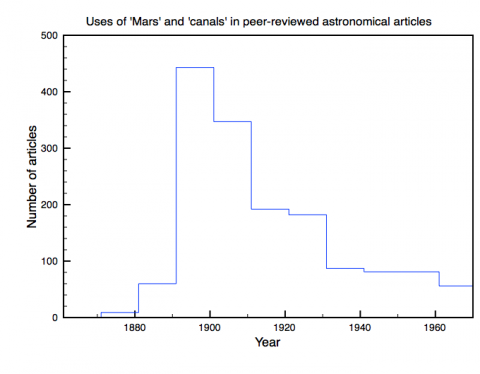

Turning to more empirical evidence, one of the plots in the first post in this series simply showed the frequency of 'Mars' in refereed journals, and there's really not much of a decline until the 1940s, and even then it is above the level of the 1880s. As I've noted, however, there are problems with this data. (One problem relevant to this question is I don't know what the proportion of the astronomers publishing refereed articles mentioning 'Mars' were professionals. At least some will have been amateurs.) Looking at the same three journals I've used in this post, PASP mostly replicated this pattern with fluctuations, though with a big spike in the 1950s (probably due to in part to the aforementioned Mars patrol); MNRAS was much the same but at a lower level and without the spike. Interestingly, Astronomische Nachrichten seems to have stopped publishing articles on Mars altogether around 1940. Maybe planetary astronomy was deemed unvölkisch or bourgeois (it was published in East Germany after 1945) but also at some point Astronomische Nachrichten did stop being a general astronomical journal and began narrowing its focus, so maybe that was why. Anyway, the number of articles mentioning 'Mars' had already more than halved between the 1900s and the 1920s, so it was already declining. But in overall, it seems to me that Mars was being studied at about the same level in the first four decades of the 20th century, though the peak was clearly in the 1900s. Equally there was a lull from the 1940s but this was only relative and of course interest began to revive when space probes started being sent there.

Jon

It might be interesting to plot the publications on the Moon and Jupiter to see there was indeed a general drop in interest in planetary astronomy. Both bodies have surfaces and cloud tops respectively that can be readily seen through even small telescopes. And compare these (and the Mars data) againt total astronomical publications, to see relative interest.

On the French connection, from memory the observatory at Pic du Midi was one of the other major centres for planetary research apart from Flagstaff and generally took a very negative view of canals.

BTW The Flagstaff observatory is well worth a visit and of course Flagstaff now is the centre for the USGS astrogeological branch

Brett Holman

Post authorYes, that would be useful to look at; but somebody else will have to do it! Well, here's a stab at it anyway. You can actually use the ADS Fulltext Service itself to generate some quick and dirty numbers -- it even provides a little thumbnail graph of the numbers (under 'Publication Year' on the left, you may have to click on the triangle to open it out). For 'moon' (it doesn't care about case so this will pick up other references to other moons, but given the idea is to check how popular planetary astronomy was that's no problem) the number of refereed articles nearly tripled from the 1870s to the 1880s, then nearly doubled in the 1890s, and then stayed at a roughly constant level until the 1940s and 1950s when it fell back to the 1890s level. Not until the 1960s did it pick up again. It's much the same for 'Jupiter', though with a much bigger peak in the 1890s (when interest in 'moon' was still growing). You can see the numbers for all articles without specifying a search term, to compare the total volume of astronomical literature as you suggest. Here the numbers are a little different. There are also jumps in the 1870s and 1880s and the 1890s appear as a definite watershed, with the number of articles doubling from the previous decade. But whereas in planetary studies things were relatively stable between 1900 and 1940, overall there was a relatively small but steady increase in that period. In the 1940s there is the same decline (interesting that WWII seems to have a clear impact where WWI does not -- a more total war, I guess), but things pick up quickly in the 1950s, in fact the dip in the 1940s seems to have had no longterm affect at all. Finally there is a huge growth in the 1960s, at more than double the level of the 1950s.

So what that says to me (speculation alert) is that planetary astronomy grew rapidly in the last few decades of the 19th century; but after 1900 did not share in the expansion of astronomy as a whole and was not able recover from the slowdown during WWII until the 1960s. In demographic terms that suggests that a large number of astronomers went into planetary astronomy in the 1890s and 1900s and stayed there for their working lives, say about 30 or 40 years; but that they were not very successful at reproducing (i.e. recruiting graduate students) and so once the 1890s/1900s cohort began retiring they were often not replaced and the field began to decline. WWII perhaps accelerated this trend, but the Space Race reversed it and planetary astronomy clearly became sexy again in the 1960s.

Jakob

I vaguely know Josh, but I'd forgotten about his work when reading these posts- I'll point him in your direction when I next see him.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, Jacob.

Josh Nall

Hi Brett - Jakob followed through on his promise and sent me here. This is all fascinating stuff, and there's so much I could say, I'm not sure where to start. Great job on the data analysis - there's a lot that can be learnt from what you've done.

First off, let me just say that the canals on Mars ARE REAL.

Only joking. At least it's nice to know that there's someone out there still standing up for Lowell.

Anyway, on to Mars and your fascinating data. On the issue of temporality, it would be interesting to know if you could break down the graphs into specific years, given how episodic opportunities to observe Mars are. The planet comes into opposition about once every two years, and only then, for a month or two, are observing conditions favourable. Even then, oppositions themselves move through a cycle of quality, with the best—perihelic oppositions—only occurring once every 15-16 years. This means that there is a definite seriality to (what I would call) 'news from Mars'. Schiaparelli observed the 'canali' during the perihelic opposition of 1877, and the next major spike in interest didn't happen until the next perihelic opposition, in 1892. Lowell then added to the growing sensation by entering the game at the very next (slightly less good) opposition of 1894. Thus, the 'Mars boom' of the 1890s was actually, to the actors themselves, viewed as a 'boom' of 1892, plus some episodic reprisals through the decade. Then things quieten down (and we see this on the Google Ngram), only to re-spike at the opposition of 1905 (when Lowell Observatory first "successfully" photograph the canals), 1907 (when many more, "better" photos are taken) and the perihelic opposition of 1909 (when Antoniadi makes his famous canal-less map at Meudon). Thus, the temporality of published material is most fascinating when considered year-on-year. But your data already supports a couple of important general conclusions that I would agree with:

1. The 1890s was the time of peak interest, but the following decade was not far behind (with both of them having peaks of interest around their perihelic opposition).

2. Interest in the canals faded slowly through the C20th. Alas, this is an area of interest for me that won't make it into my PhD, for want of space. But it's certainly simplistic to say, as Dick and others do, that Antoniadi's map of 1909 kills off the canals for good. Of course, data hits like the ones you map only register comment, not support, but I still see a lot of open discussion about the canals up to mid-century. Unpacking the reasons for this would require a complex analysis of the relationship between "elite" astronomical discourse and its relation to forms of mass media, something my own research tries to do for the years of peak interest but which would require a whole other PhD for the years after 1909. As you say, in the period 1890-1910 the distinction between 'academic' publications and other forms of mass media is not remotely hard-and-fast, with a lot of the astronomers at the centre of the debate (not just Lowell!) using a wide variety of publications and genres to discuss and debate the subject (in my own research I particularly analyse astronomers' use of newspapers and encyclopaedias). But after 1909 I suspect that this generically promiscuous setting for the debate begins to bifurcate, with the newly minted discipline of "planetary astronomy" retreating more into academic journals. Meanwhile, mass media keeps up the interest, as the Ngram shows quite clearly (though we need to remember that Google Books’ database contains a lot of academic journals too).

On the types of publications you look at: 'peer reviewed' might not be quite the right way to describe many of these journals. Publications like the JBAA and PASP tended to be ruled over by one or two editors, who did much / all of the gate keeping. Although I'm not sure about this (and would love to know more), I don't think these kinds of journals sent out papers for peer review. My impression is that the editors just published what they saw fit, and asked colleagues for advice only when they needed to. Having sifted through quite a few astronomers’ archives from the 1890s/1900s, I don’t remember seeing any letters from editors asking astronomers to referee articles.

Take the PASP. Founded in 1895 by the imperious Edward Holden, Director of the Lick Observatory, this journal was effectively the Lick's 'house' journal for at least it's first few decades of existence, and thus much of its content was determined by Holden and his 1898 successor, W.W. Campbell. A lot of the articles were written by various members of the Lick staff. This is really clear in the case of Mars. The Lick was, from the outset, vehemently anti-Lowell, and therefore, especially in its first few years under Holden, the PASP carries a lot of anti-Lowell material. Thus, its content, measured numerically, is, in a sense, not really much of an indicator of the wider discipline’s interest in the Martian canals. It’s a measure of the Lick’s interest. The quite dramatic drop your data shows from the 1890s to the 1900s is, I think, an indication that Holden was much more vocal in his campaign against Lowell that Campbell was.

I think a similar thing could be said about the JBAA. From the outset two anti-canal advocated, E. Walter Maunder and Antoniadi, were actively involved in running the Mars section of the JBAA. Thus, they published a lot of reports from members regarding the canals, but the tenor is mostly negative (Maunder and Antoniadi had all canals expunged from the official JBAA maps of Mars after Maunder’s school boy experiments in 1903 – see Hoyt p.165).

Canal advocates like Lowell, though they did debate the subject in ‘academic’ journals, tended to rely more on newspapers and popular magazines (though the divide is not nearly as strong as most of the secondary literature on the subject makes out).

Anyway, to wind up my rambling – what you’ve shown is in itself fascinating, and unpacking the data a bit more, especially for what happens after 1909, is a research project that awaits its historian. I might get on to this after I finish my PhD (I’m nearly there...) but I might be a little sick of Mars by then. Thanks again for your fascinating posts.

Brett Holman

Post authorJosh, thanks for your comment-and-a-half! I'm relieved that my fairly naive and very broad analysis more or less fits with what you've found from looking at the evidence much more closely. The point you make about the lack of peer review, for example, is certainly something I wasn't aware of (though it makes sense that peer review had to evolve some time!) I suppose it would be better to think in terms of audience, whether popular or scientific (with amateur astronomers straddling both). And clearly, given how the results are dominated by a few journals, editorial biases matter a great deal. I'm also glad to get some backup regarding Dick's placing too much weight on Antoniadi and 1909, particularly since it's such an impressive book in most other respects!

It's possible to break the numbers down by year instead of decade, though I don't have that data. But ADS Fulltext gives you a little thumbnail of the numbers for your search over time, and if you choose a small enough window it gives you the numbers for each year. Just looking by eye there is some evidence for a periodicity of 2 years or so (in the 1890s there's a pronounced step function, it stays the same for 2 years then jumps up, peaking in 1897). But you'd probably need to do some actual statistical analysis to be sure (particularly since Martian oppositions come every 26 months or so, rather than 24, not so easy to eyeball when the data is binned in years).

Good luck with the PhD; it's such a great topic and hopefully you will publish on it -- though I can fully understand the desire to do something different when you're finished! Whatever you do, stay away from Alternative 3...

Josh Nall

Thanks Brett,

Yes, data by year is also a blunt tool - by month would be better! It's interesting to note that the peak is 1897, suggesting something of a lag for journal coverage (versus the immediacy of newspapers, which is something I talk about a lot in my PhD - I'm giving a paper on just this subject at the history of science megaconference in Manchester this summer - I don't suppose you'll be there?).

Yes, Dick's book is generally great - it's worth metioning that no one, as far as I know, really pays much attention to persistent popular interest in the canals after 1909. Anyway, if you want to read more good stuff about the canals, I can recommend two books in particular:

K. Maria D. Lane, 'Geographies of Mars', Chicago UP, 2011 (which I review here: http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=8822766 )

&

Robert Markley, 'Dying Planet', Duke UP, 2005.

Strauss's 2001 biography of Lowell is also pretty good.

I certainly plan to publish the material in my PhD once it's done. Whether as a book or seperate papers is not decided yet. In the meantime, I'm very much looking forward to reading your book - I am something of an aviation nut myself. Maybe I can persuade BJHS that's it's close enough to history of science to warrant a review...

Brett Holman

Post authorI'd love to be in Manchester (your paper sounds interesting -- I've encountered similar issues in airpower literature, where I look at press coverage as well as books in relation to popularisation) but my overseas trip this year will take me to Wellington to talk about phantom airships. Thanks for the tip about Markley, and that's the second recommendation I've had for Lane's book, so I'll definitely look that up. I read Strass's Lowell biography when it came out, I recall finding it a bit frustrating -- I think there just wasn't enough canals in it, too much about Japan, Boston, etc. But I was still an undergraduate then, I would probably appreciate the context more now!

I hope you'll like the book when it eventually emerges. Surely BJHS would want to review it -- science, technology, it's all the same right? Wait, come back, I was joking…

Jakob

Well, the BSHS do cover hist of tech as well, so let's hope so...

Josh Nall

Sounds like the BJHS review might just work then, although, Jakob, I take it that we'll have to arm wrestle for the rights to write it?

Yeah, Strauss's book is a bit heavy on the Japan / Boston side of things, but it's useful context compared to the usual "he was a crackpot popularizer" stuff that one sees. Anyway, good luck with the phantom airships paper.

Brett Holman

Post authorThanks, Josh.