Wednesday, 28 September 1938

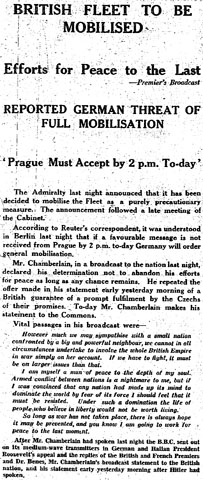

The German ultimatum for the Czech withdrawal from the Sudetenland by 1 October remains. But there is a report of a new deadline: the ultimatum must be accepted by 2pm today, or else Germany will mobilise its armed forces (Manchester Guardian, p. 9). Hungary has already begun mobilising, and the Royal Navy has been given […]