Airminded world tour 2013-14

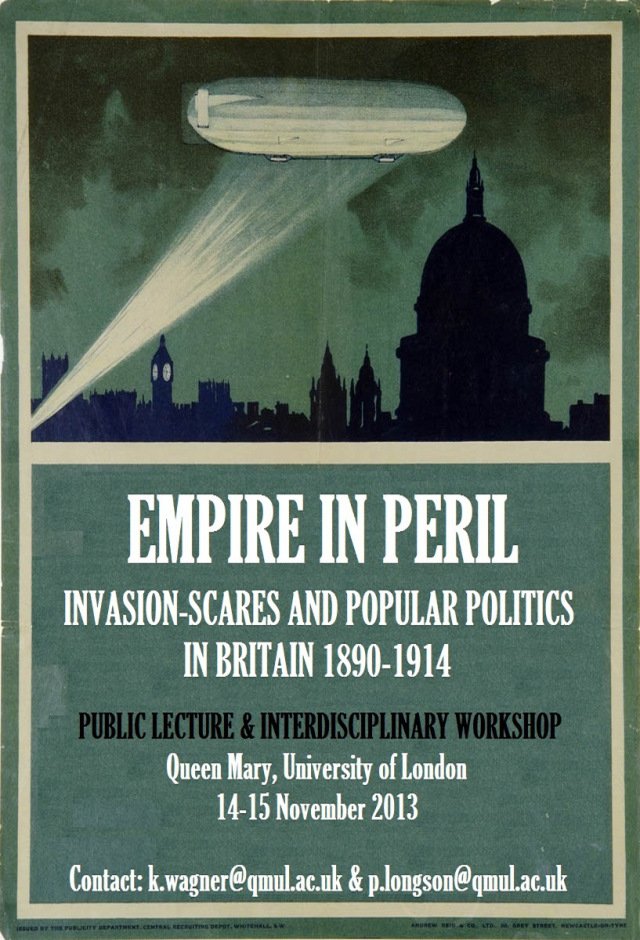

It’s quite a small world tour, admittedly, but two gigs in two countries just qualifies, I think. Little to no moshing is expected. First, I will be giving a paper at the Empire in Peril: Invasion-scares and Popular Politics In Britain 1890-1914 workshop, which is being held at Queen Mary University of London on 14 […]