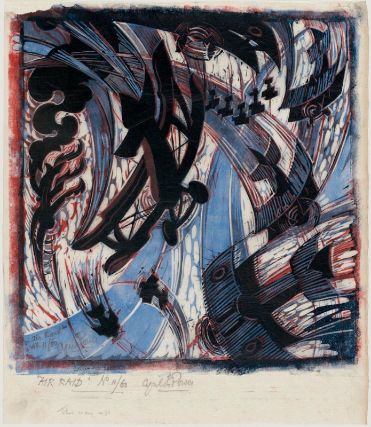

Air Raid

Cyril Power, Air Raid (1935): British biplanes tangling with an unidentified enemy against a smoke-filled sky. It is tempting, given the date, to see this as an air raid of the next war, especially given Power’s marked interest in machines and speed and influence by Futurism and Vorticism. But it could just as well be […]