The superweapon and the Anglo-American imagination — IV

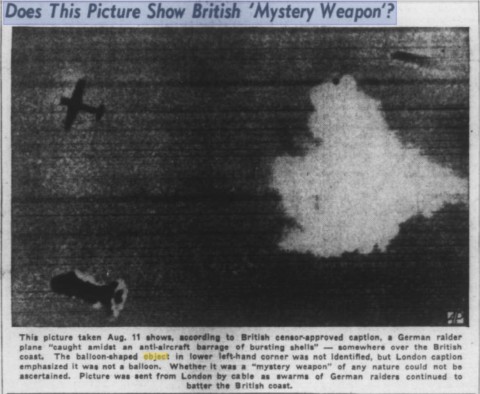

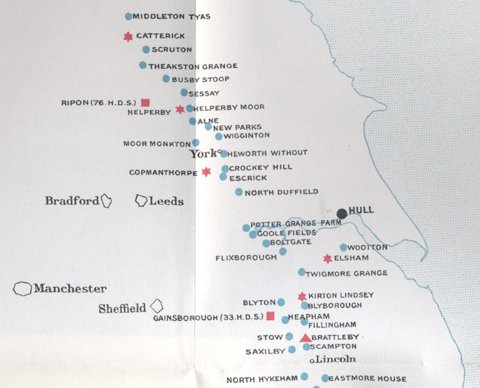

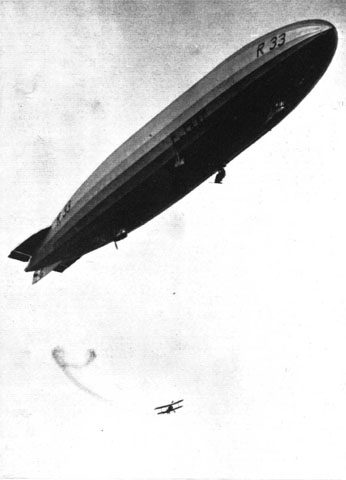

So we’ve seen American claims of a British secret air defence weapon in the Battle of Britain; American claims of British secret air defence weapons in the mid-1930s; and American ideas for superweapons to break the deadlock of the First World War. What do I mean suggest by these examples? Why have I called these […]