Acquisitions (omnibus jet lag edition)

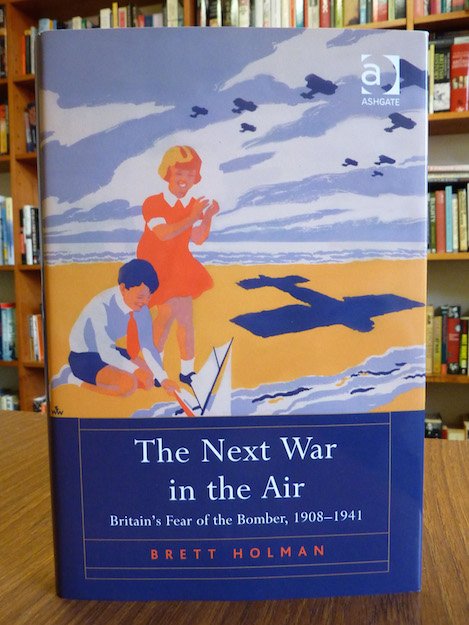

So, I bought so many books in the UK that I had to post some of them home to myself; here are some of them. You might ask why I didn’t just note down the names of all these books and order them when I got back to Australia, but such a self-evidently absurd question […]