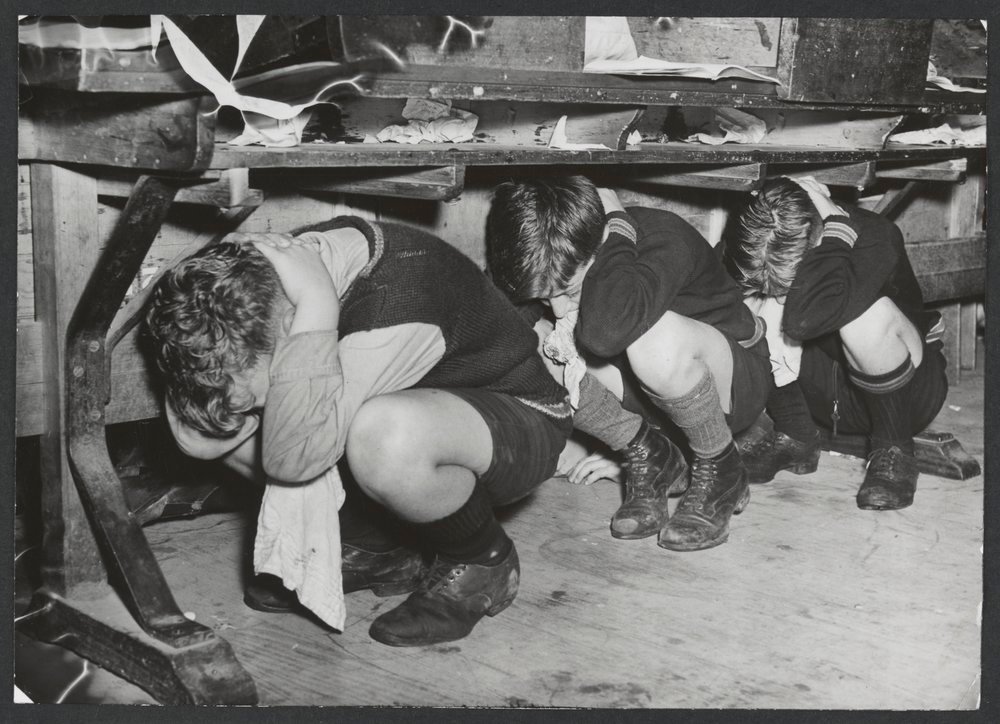

Panic Day in Oslo

10 April 1940 has remained in history as “the great panic day”. The reason for this designation is the panic that spread through the population of Oslo, after the rumors of the British bombing of the capital had spread. Here you can see how the Oslo people rush out of town on foot, on bicycles, […]