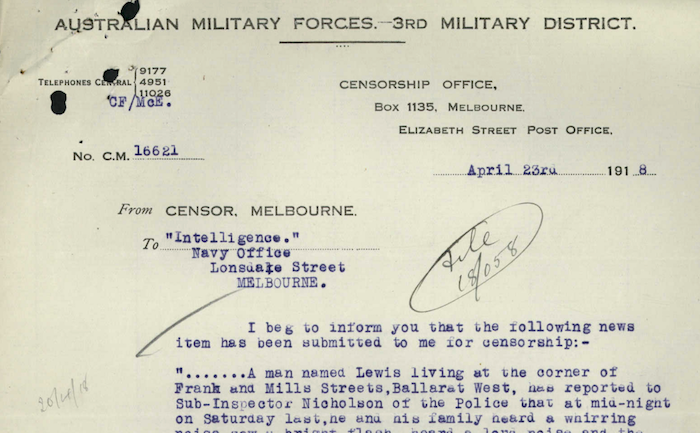

Tuesday, 23 April 1918

NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066, page 212 is a telegram from Captain C. Finlayson, censor for the 3rd Military District (Victoria), to ‘Intelligence’, Navy Office. He is passing on a newspaper article which has been submitted for censorship: A man named Lewis living at the corner of Frank and Mills Streets, Ballarat West, has reported to Sub-Inspector […]