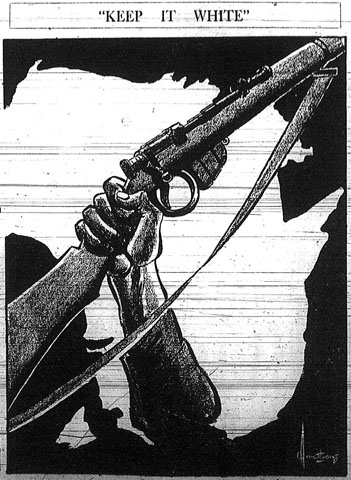

Slap the Jap and make the Hun pay

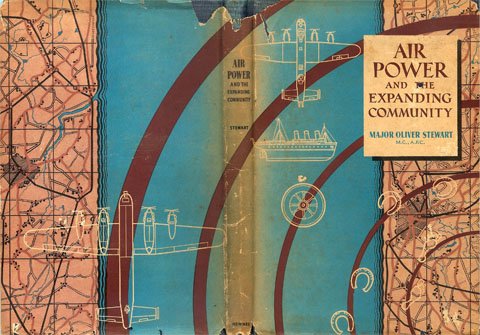

[Cross-posted at Cliopatria.] Or, Australia strides onto the world stage. Today is the 90th anniversary of the signing of the Versailles Treaty and thus of the Covenant of the League of Nations (which formed the first thirty articles of the Treaty). This was a fateful moment, with heavy consequences for those who lived through the […]