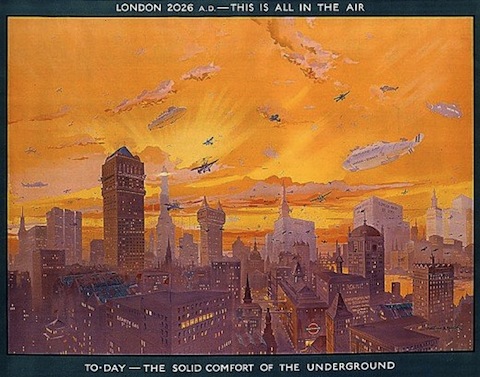

Airmindedness is a word which gets bandied around a lot these days — okay, not actually a lot, but it’s not just me either. But I think it’s too broad a concept; at the very least, it needs to be divided into positive airmindedness and negative airmindedness. I mostly write about negative airmindedness. This more or less is the attitude ‘Aviation is vitally important to the nation because it is incredibly dangerous‘; the previous post is a good example of this. In Britain, I would argue, this was the predominant form of airmindedness in Britain between the wars, due to the perceived danger of a knock-out blow from the air. But mixed in with that there was also positive airmindedness: ‘Aviation is vitally important to the nation because it is incredibly beneficial’. (Before 1914 this was stronger, though the phantom airship panics would suggest that even then negative airmindedness held sway.) Above is an example, a 1926 London Underground poster by Montague B. Black.

LONDON 2026 A.D. — THIS IS ALL UP IN THE AIR

TO-DAY — THE SOLID COMFORT OF THE UNDERGROUND

It presents a vision of London a hundred years’ hence, the far-off year of 2026, drawing on the futurism of aviation to sell the (sub)mundane transport of today. (Airmindedness was very often about the potential of aviation than its reality, the future rather than the present.)

The sky is full of exciting promises: autogyro airtaxis! Airships to Australia! A London Bridge Air Depot! These are all good things (except if you value London’s architectural heritage, perhaps).

But as I say, this kind of positive airmindedness is not typical of Britain. I think it is safe to say that it was much more typical of the United States, for example, a reflection of that nation’s more optimistic attitude towards technology in this period. That’s why when talking about airmindedness it’s critical to pay attention to the national context: as brilliant as Joseph Corn’s The Winged Gospel is, for example, it would be a mistake to think its portrait of positive American airmindedness applied to Britain where negative airmindedness held sway.1 Different countries had different forms of airmindedness at different times.

I would add one caution: the distinction between positive and negative airmindedness is not quite identical to that between civil and military aviation. For example, military aviation can be seen as positive if you believe that it will deter war or end them quickly and with a minimum of bloodshed (AKA ‘the bomber dream‘); and civil aviation can be seen as negative if you believe that they can be quickly converted into bombers and used in a knock-out blow (AKA ‘the commercial bomber‘). It’s all in the context.

Additional image source: The Retronaut.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Joseph J. Corn, The Winged Gospel: America’s Romance with Aviation, 1900-1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983). A book on “Britain’s Romance with Avation, 1900-1950” would be a very partial account indeed, though one on 1950-2000 would be fairer. [↩]

I love the mild pun — “all up in the air’ meaning an uncertain, as well aviation-centred, future.

The scene reminds me of the highly air-minded opening scene of the movie “Metropolis”, the great future city surrounded by swarms of aircraft coming and going, also meant as a positive image, I think. (From the outside, Metropolis appears wonderful and prosperous, it’s not until you get below ground that you see how the workers are mistreated to maintain the machinery, etc.)

Yes, I think you’re right about that scene in Metropolis, it signifies progress in all its shininess, but its hides the true cost of technology. Neutral airmindedness, if not negative?

The 1929 film High Treason contains one of the few other British examples of this that I’m aware of — see a still here. It’s sometimes said to be influenced by Metropolis (1927); but now that I look at it the 1926 London Underground poster is a much better fit for that scene!

How can we be looking at this kind of airmindedness in this period in Britain and not mention Sir Alan Cobham?

And to take Sir Alan, he was advocating and enabling airmindedness (pro-active, ergo positive) but there was always an element of ensuring that Britain was just keeping up with the pace of the thing, and I don’t get a ‘military’ or ‘negative’ slant beyond a defensive element in his projects.

Of course; I wasn’t trying to write a history of positive British airmindedness but just put the idea out there. (Actually, I wasn’t originally trying to do that either, I was just going to put up the pretty pictures but then it got away from me!) Cobham certainly fits into positive airmindedness, and he was one of the most prominent supporters of it with his flying circus and National Aviation Day tours. (When writing this post I found a British Pathé clip about Cobham entitled ‘Get Airminded!’) But that is mostly in the late 1920s and early 1930s. It’s telling that Cobham’s National Aviation Day inspires and is overtaken by Empire Air Day, a much more martial affair; Cobham himself seems to have turned away from promoting airmindedness in favour of his air refuelling experiments. Anyway he’s much less visible.

Mind you, I nearly bought an old Imperial Airways poster the other day – 10 and a half days to AUSTRALIA!

VH-USC looking pretty good over a vaguely constructivist/suprematist part-globe…

Sometimes I think 10 1/2 days Australia-UK would be better than 24 hours — at least you didn’t have to try and sleep on the plane and it avoids the jetlag problem…

Pingback: Flitting, 1950 | Airminded

Pingback: Anxious nation? — I – Airminded

Pingback: The great air-liner of the future – Airminded