In Culture in Camouflage: War, Empire, and Modern British Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), Patrick Deer discusses airminded fiction for boys from the 1930s and suggests that (78):

In their own cheery way, these boys’ flying stories echo the mythos of the flying übermenschen so dear to the fascist imagination. In their patriotic exuberance, these flying stories remain disturbingly oblivious to the darker side of British air power, curiously out of step with the apocalyptic fears so much a feature of 1930s popular culture.

I’m not so sure about this. I’ll grant the first sentence — Biggles himself is certainly a flying übermensch — but then again, didn’t just about all adventure fiction, of whatever subgenre, feature steel-eyed square-jawed two-fisted men of action? And flying adventure stories would necessarily simply have flying versions of same. Still, it’s not wrong as such.

The second sentence is more problematic. Most airpower writing of the 1930s was ‘oblivious to the darker side of British air power’, if you place the emphasis on ‘British’. It wasn’t a problem for Britain to possess airpower, because it believed to be peaceful and non-aggressive, and could be trusted to use it responsibly. It was everybody else’s airpower which was the problem. Similarly, the ‘apocalyptic fears so much a feature of 1930s popular culture’ were almost always about London being wiped off the face of the Earth, and not, say, Hamburg or Dresden. Only pacifists denounced British airpower as such (and by ‘only’, I don’t mean to imply their views were not widely shared, but they were in a minority, at least in print). It should not be surprising that juvenile fiction did not do this as well.

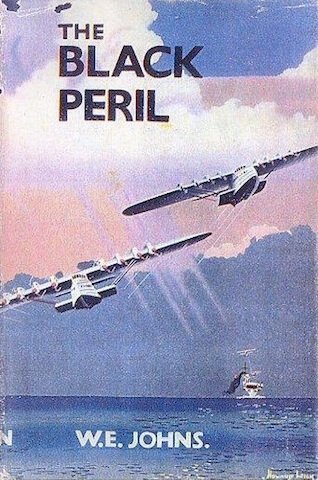

So Deer’s assumptions here are only true if you read them more broadly, i.e. he must not be referring to critiques of British airpower specifically but to fears of the knock-out blow more generally. But then I don’t know that his conclusion is actually true, because juvenile air stories did talk about this darker side. At least sometimes. Consider the sixth Biggles novel, The Black Peril, which was published in March 1935 (and set and probably written in 1934).1 The plot revolves around a, er, plot by Germany and Russia combined (with the Russians the main instigators) to bomb Britain using long-range flying boats (with silenced engines and bigger bomb bays than anything Biggles has ever seen. The cover illustration suggests something like a super-Do X). Biggles, Algy and new chum Ginger rumble the nefarious scheme by stumbling upon secret enemy bases laid out along the east coast of England. Near the bases, submerged under the sea, are navigational beacons, to show the flying boats where to touch down. There they would refuel — thus effectively increasing their range, enabling them to fly from Russia — and then proceed to attack Britain, presumably in a sneak attack. The precise targets are not given. But Biggles concludes that

There was not the slightest doubt that at some date in the near future it was intended to blow England out of the water by wholesale bombing.2

Of course, the plot is foiled by the actions of Biggles and co., which is unlike more adult knock-out blow novels where the threat to Britain is usually carried out. Nor is the air menace dwelt upon throughout the book; its nature only becomes clear near the end. But it is there.

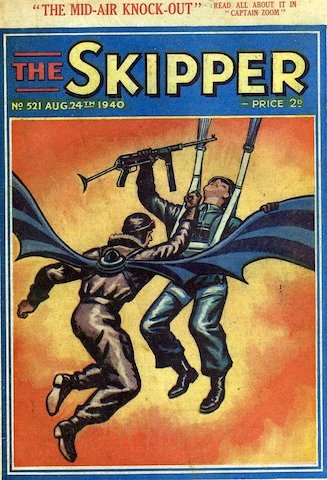

I suspect that this is not atypical. Children were not oblivious to the fears their parents might have held about the bomber, though they may not have fully understood or even fully shared them. So fiction aimed at children wouldn’t necessarily ignore those fears but might address and try to assuage them in some way, as W. E. Johns did in The Black Peril. A second, and last, example is Captain Zoom, Birdman of the RAF, who Deer introduced to me. Captain Zoom was a comic book superhero who debuted in The Skipper in the summer of 1940. A pilot in the RAF, he preferred to fly using his own invention, a pair of artificial wings which enabled him to fly like a bird. Using these he was able to foil any number of Nazi plots, including one in which a mad scientist plans to work RAF prisoners to death by building an invasion tunnel from the occupied Channel Islands to Cornwall.3 I haven’t seen a full list of Captain Zoom stories but given how closely they seem to track the war’s progress, I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find him helping to fight off the night bomber at some point.

And, yes, I did pretty much write this post to justify putting up this image of Captain Zoom socking it to a Nazi paratrooper.

Image source: Biggles from AbeBooks, Captain Zoom from Comicvine.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

And who among us would deny a chap such simple pleasures? Not I…

Really great post! Doing some recent research I was reminded that historians such as David Edgerton and Robert Wohl insist that peaceful and positive visions of the future of aviation predominated in the interwar years, and that it is only now that historians concentrate on dark and apocalyptic images (which are simultaneously much more exciting as well!) All very interesting to consider.

If you can’t punch out Nazi paratroopers who can you punch out?

Jakob and George:

You are both most accommodating.

Idle:

Thanks! Do you have a cite for Edgerton? It’s been a while but I thought he argues that historians have underestimated the importance of the military side of aviation to the industry’s interwar development (hence the ‘warfare state’), which is not quite contradictory but not very consistent either. But personally I do admit to being drawn to the apocalyptic and neglecting the more positive images of aviation. I try to keep an eye out for the latter, and I do think that in Britain (unlike probably in the US) they were not as culturally powerful, but I can’t exclude the possibility of primary source bias.

Edgerton does spend some time talking about intellectuals’ claims for the peaceful internationalist influence of aviation, and contrasts this with the nature of the Warfare State, but he does mention things such as the international air police, which would obviously have been backed by military force. (I don’t recall off-hand if this is all in England and the Aeroplane or whether this is also in Warfare State.)

One of his PhD students, Waqar Zaidi, has recently completed a thesis on international air police stuff and the post-war proposals for international control of atomic power; presumably there’s good stuff in there as well.

(Tangentially related, Edgerton’s new book is out in a month or two, and there is a launch event at Imperial on March 16th – any Airminded readers likely to be there?)

I’ve got to be at work on the 11th, more’s the pity. DEHE’s book looks excellent: it fills an obvious gap in the literature which he left open in Warfare State and which Overy also skipped over in Why the Allies Won: how the British organised their war effort.

For 11th above read 16th, natch

I got it from England and the Aeroplane, which I suppose is part of a larger argument regarding excitement about, and investment in, interwar aviation. He argues that most people hoped that it would facilitate international cooperation. (I wrote down in my notes the preface and early sections of the book… if that is correct.)

Thanks, it might be the bit on pages 40-1, which is where he talks about the international air force. (Note that ‘air police’ == ‘air force’; the word police was often used because of the peacekeeping function but was misleading in terms of its intended composition and usage). I think — modest cough — that the international air force was an attempt to rescue collective security (which in the League of Nations version was predicated upon slowing down the rush to war) from the sheer speed of the knock-out blow. So it was a positive use of airpower but seemed necessary only because of its negative uses — the exception that proves the rule.

I’d love to be at David’s book launch but I suspect I won’t be in London that day…

Oh, and on the international air force see the latest post at Ether Wave Propaganda.

I’ve realised what bothered me about the quote: “the flying übermenschen so dear to the fascist imagination.” He’s sliding ‘fascist’ and a German (umlaut-enabled extra-points) man-term in which removes the stories from the continuum of (British) Imperial internal propaganda / self-narrative, which is really where such boy’s aeronautical stories sit.

It’s as (in)appropriate/(in)accurate to suggest the British newsreels of the 1930s pandered to ‘the fascist imagination’; in a way, they did, but more that fascism had adopted the previously Imperial vision.

Biggles is more interesting (and complex) than many equivalent children’s stories, but they are all just another aspect of the boys adventure stories featuring ships, or science or colonial patronage, and I’d be surprised if you could find any ‘darker side’ kids ‘imperial adventure’ books well into W.W.II.

Britain always had ‘stout chaps’ always ‘doing the right thing’.

It took Molesworth’s ‘Whizz for Atoms’ for that to appear in the 1950s, I’d suggest.

I got Molesworthed – I meant it took Nigel to bring a dark vision to boy’s adventures in the air.

Yeah, about that “boy’s-adventure-fascist-imagination” nexus that we all think we can see. I’m going to throw out there the observation that the heroes of that era that I remember are all distinctly dark skinned. Doc Savage is a “man of Bronze.” Conan is a dark, brooding Cimmerian. Tarzan (like the somewhat later Eric John Stark) has been permanently tanned, however that works. John Carter may be pale, but his supporting cast, including his wife, are all Red Martians. The Shadow is “dark.”

Now admittedly these are all American rather than British heroes. That said, we have the pulp hero as Janus. One face, the face that our idea-of-the-world-as-it-ought-to-be stares, all Aryan hero, into the story. The other, the very personal face brought home to us by the stereotyped descriptors applied to the hero in every outing, stares back at us, distinctly dark and perhaps even non-Caucasian (certainly not WASP!)

If I were a smart book-talking guy, I’d throw it out there that this kind of fiction has as a very important role the facilitating of the self-creation of mature identity. The way that the market has rewarded this kind of character might tell us something interesting about the way that supposedly essential racial and national characteristics are in fact deployed as a social strategy. I would bet that there’s a Janus-faced reading of class in the Biggles books, in the same way that there is a double reading of race in North American pulp fiction.

But I’m not, so I won’t.

Mike Paris has done some good work on the assumed role of fiction in the boy->man narrative, and how this relates to the changes in government-sponsored propaganda fiction of WW1.

Re collective security ipso facto, this just turned up in my Academia feed:

‘A Most Dishonest Argument’?: Chamberlain’s Government, Anti-Appeasers and the Persistence of League of Nations’ Language Before the Second World War *

Author: Andrew David Stedman

DOI: 10.1080/13619462.2011.546105

Published in: Contemporary British History

Abstract

This article argues that both Neville Chamberlain’s National Government and many anti-appeasers used and abused the language of the League of Nations in the years before the Second World War, long after they had abandoned Geneva itself as an effective instrument to maintain peace. It concludes that while many formerly pro-League figures could not bring themselves to admit the truth about the demise of collective security—and were, in effect, deluding themselves—this was, in many cases, ‘a most dishonest argument’; born out of party politics and the need to keep world opinion on side in the pursuit of alliances.

Erik:

Interesting, but as you note dark-skinned can also mean tanned. In the imperial context that suggests to me the rugged outdoorsman — dark-skinned because they are men of action, outside actually doing things like hunting or oppressing natives, not hanging about indoors reading books and fainting from the heat. Think the stereotypical ‘bronzed Aussie’ (which I am not).

Pingback: On the self-promotion of W. E. Johns | Airminded