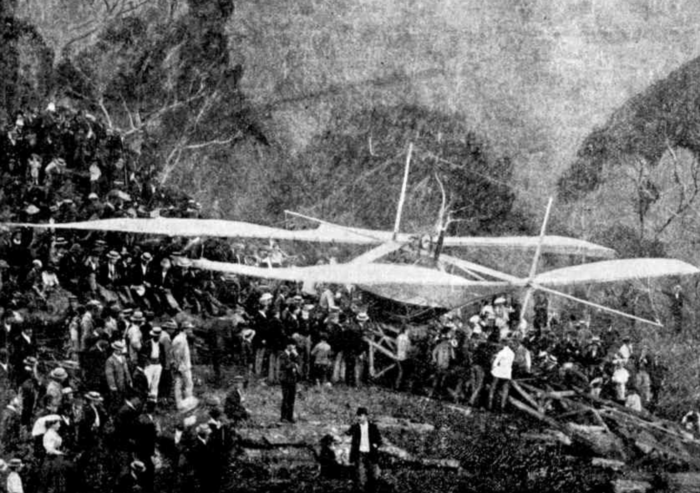

So, who was behind the Chowder Bay flying machine? In November 1894, the month before the ill-fated flight attempt, stories appeared in the Sydney press about what sounds like a very similar ‘flying machine’ being exhibited in a vacant lot behind the Lyceum Theatre. Given the reported plans for a launch over Sydney Harbour, it’s clearly the same machine:

The object of the exhibition is to raise funds for laying a tramline for the trial, which will be mode on an elevated line across the waters of Sydney harbor. The machine is constructed of large sails, four in number, wnich are in appearance much like the mould boards of a plough, only much more flat. These are secured to stays, which have in the centre an elliptical shaped affair in which is a small boiler, and attached to the outside of which are thin strips of canvas, which are to revolve when the machine is in motion.1

Importantly, this article identifies the flying machine as being ‘Mr Gordon’s’.2

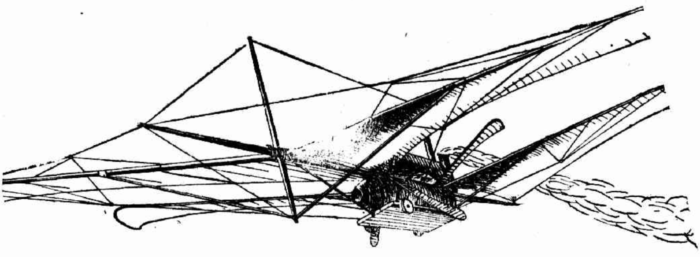

This clue then leads to a lengthy article which appeared in the Daily Telegraph in October, about a flying machine, illustrated above, located at the Technical College in Ultimo. It names the inventor as N. R. Gordon and provides more details about the machine itself:

In repose the machine is a thing of mysterious seeming, with a big barrel-shaped body in a canvas skin, an interior economy consisting of a small engine and boiler, numerous arms stuck out endways and sideways, and no legs. Yesterday Mr Gordon walked round it for half an hour and explained its points to a reporter.

‘Its weight,’ he said, ‘is 1050lb. It has four large wings, covering 970 square feet, and four wing propellers, which are 8ft long, but will probably bo made 9ft after one or two experiments, so as to

utilise the full steam power.’3

The engine could develop 6.5 horsepower. The reporter is initially sceptical — ‘Everyone knows what a flying machine is. It is a machine that cannot fly’ — but treats Gordon seriously.2

These, and a number of other details, Mr Gordon explained with patience and care. He has worked long and hard at the business, and apparently there isn’t any such word as fail in his lexicon. He has proved the thing so thoroughly, also, that there really seems to be something in it.2

Gordon’s claims as to the potential of his machine are also given a respectful hearing:

No, Mr Gordon said, he hadn’t been up yet. But he seemed to look forward to an early soar. This machine, ho said, was merely intended as an experiment to demonstrate tho possibility of safely carrying weight through the air. ‘With wingbones and backbone of hollow steel instead of wood,’ he added, with calmness, ‘I would guarantee to go from Sydney to Melbourne in six hours.’2

How justified was this confidence?

‘The spread of wing is 64ft. It’s much more important, you see, to have large spread of wing than wing area. Suppose, for instance, that the machine is travelling 30 miles an hour, or 44ft a second, then. It will cover 5632 square feet of air in one second. The idea that wing area gives support is wrong; what does give support is the area of air covered in a given time. In this machine the measurement is 64ft spread of wing by 41ft of velocity per second, and that must be taken twice over, because there are two pair of wings the same size […]2

That seems reasonable, as far as it goes (as I understand it, lift varies with the wing area, but with the square of the air speed), but this is… not so great:

The big wings, it seems, don’t move, but are stretched tight to give support. ‘Experiment has convinced me,’ the inventor explained, ‘that the wing motion is necessary to artificial flight. The Maxim machine, which has just been completed, is worked by screws, and tests of it show that there is an enormous waste of power through ‘slip’ — which you avoid, of course, with wing-propellers. In that way Maxim lost about 141 per cent, of his power; while in my machine all the power is given back to me by the rebound of air from the downstroke […]’2

So it seems that Gordon’s flying machine was a variety of ornithopter; the big wings are fixed and provide lift, but the ‘wing-propellers’, the relatively small (8ft) paddles sticking out the side of the fuselage in the drawing above, flap up and down. They look like they might be angled or scooped, to provide forward thrust? Hmmm. And with a power-to-weight ratio of only 0.0062 (a quarter of that of the Wright Flyer), well, I’m not convinced.

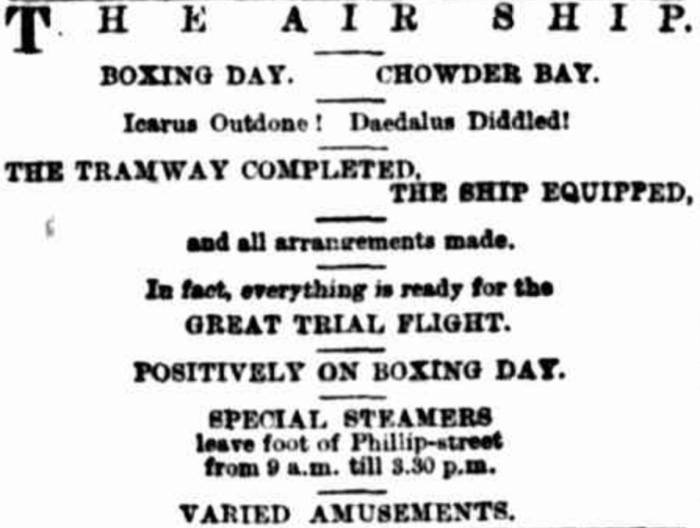

Gordon spoke of his plans to fly the machine off ‘a little inclined tramway to be put up on a sloping cliff somewbere on the harbor shore’, without a passenger (though he is very insistent on the point that, unlike Maxim’s flying machine, this one cannot capsize).2 This is basically what happened at Chowder Bay on Boxing Day — as advertised above — but it seems that Gordon was not actually involved in that fiasco.4 A couple of days later, he spoke to the Evening News and claimed that ‘A fortnight or so before Boxing Day […] he withdrew entirely from the enterprise on account of the impossible conditions offered to him’, and moreover

(1) there was no trial — no attempt at a trial — made; (2) no steam was up and the machinery was not in motion when the ‘ship’ was started down the tramway; (3) that the situation selected for the tramway was notoriously a bad one; and (4) that the conditions under which the alleged trial was made naturally foredoomed the attempt to ignominious failure, even had the engine being [sic] working the wings.5

Speaking ‘very strongly on the matter’, Gordon added that

A dead horse […] could not be expected to jump a fence; and the conditions under which the so-called trial was made were analogous to his parallel. Certainly a dead horse could be lifted over a fence and dumped down on the other side, but no just person would assert that the horse had tried to jump the fence and only succeeded in falling on the other side.2

It looks like whatever deal Gordon made to finance his machine — presumably including the exhibition behind the Lyceum as well as the launch at Chowder Bay — fell through for some reason, and he lost control of the machine and the trial, which is why he wasn’t even named in the press coverage. (‘Daedalus Diddled’, indeed.) The exhibitors presumably had nothing to lose and went ahead with the spectacle of dumping the machine into the sea. A shame for Gordon, but even if it had enough power, this thing would never have flown.

But this wasn’t the end of Gordon’s aeronautical endeavours, nor even the beginning — of which more in another post!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.