The planet Venus normally sticks close to the Sun and so can only be seen very shortly after sunset, to the west (or before sunrise, to the east, when it is a morning star). But every 584 days, when it reaches maximum elongation in its orbit, it is far enough from the Sun in apparent terms that it remains visible for quite some time after dusk. It also relatively close to the Earth at this time and so unusually bright: only the Moon is brighter. At such times Venus dominates the western sky and it can be very startling, especially for the infrequent stargazer.

As it happens, Venus reached maximum elongation on 11 February 1913, right in the middle of the phantom airship scare. The above thumbnail probably isn’t very clear, but the full-size version, made with Stellarium, shows the western horizon from London at 8.30pm on 21 February 1913, the beginning of the scare’s peak. (London without any buildings, light pollution or clouds, admittedly, but the view would have been roughly the same from anywhere in the British Isles.) Venus can be seen low above the horizon, almost exactly due west, and extremely bright (apparent magnitude -4.1, though extincted by the atmosphere to -3.2). Anyone who happened to glance in that direction would see a brilliant light hovering in the distance, very different to the other stars and even planets. If they watched it for a few minutes they might see it drifting northwards and perhaps sinking lower; if there were clouds scudding by or trees waving in the wind the effect might be enhanced. It would be very easy to think an aircraft was flying about, equipped with a searchlight.

And reading through the press accounts of mystery airships from 1913, it does seem that quite a few were caused by Venus: many of them describe a bright light low in the western sky in the early evening. Anything before about 10pm, when Venus set (or a bit earlier, depending on the local horizon; say 9.30pm), is suspect. Here’s one example, from Dundee on 2 March (Dundee Courier, 3 March 1913, 5):

Two men who are in the Corporation employ, were standing talking in Bell Street about nine o’clock, when their attention was attracted by a bright light in the western sky. They both observed it at practically the same time.

At first it appeared dimly, gradually increasing in strength until it flashed into great brilliance, resembling a powerful acetylene-lamp. The light gradually receded into the darkness, but it burst forth again in all its brightness a minute later. The second time it as quickly disappeared.

If these men weren’t seeing Venus and thinking it was an airship, it’s very odd indeed that they didn’t also see Venus as well as an airship. It was so bright that it just could not have been missed — though it’s possible that it could have been obscured by clouds, buildings, etc. But surely that couldn’t have happened in every case, and I haven’t found any examples of anyone seeing Venus and an airship. Here, in fact, the fading in and out is suggestive of clouds passing in front of the planet.

It would be tedious to go through each and every mystery airship sighting and analyse it to see if Venus fits. So I’ve done the lazy thing and tabulated two sets of variables for each one, or rather each one which for which enough data is available: the direction the airship was first seen in, and the direction it was last seen in. (Where conflicting accounts were available, I weighted each one so that the total for each sighting adds up to 1. Similarly, when a direction was given as, for example, east-southeast, I split it into east and southeast and weighted each as 0.5.) If Venus was a significant factor in the scare then there should be a bias towards the west. And this appears to be the case.

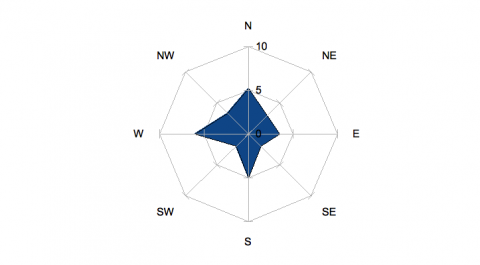

This is a radar chart of the initial directions (made with nothing more sophisticated than LibreOffice). Here west is indeed the most common direction, reported nearly twice as often as east, but it only just edges out north and south.

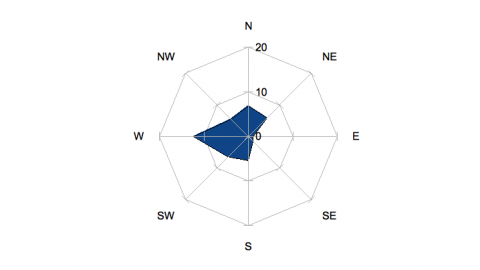

The final direction chart is much more strongly in favour of west: it is nearly twice as common as north, more than twice as common as south, and more than twelve times more common than east. That last is interesting: all else being equal, airships flying to or from Germany would presumably be seen flying to or from the east, but that’s actually the least likely direction in both charts. Sometimes it was argued that the mystery airships came from France, and at least south is much more common than east, though it still much less common than west, and for that matter a little less common than north.

What does all this prove? Not much. My classification of the directions is somewhat subjective, due to the lack of detail in most press accounts. Rarely do they clearly give compass directions; it was more usual to make reference to some landmark such as a nearby town or hill. Similarly the locations of the observers was not always given precisely, which could mean that my estimate of the direction is off considerably. And when it is said that an object was seen heading in one direction, that might just have been an inference on the part of the witness: for example, they may have seen it to the west and thought it was flying north, and so reported that it was flying northwards. I haven’t worked out what level of sightings in any one direction would be significant in a statistical sense, so despite the seeming precision of the plots this exercise is not at all scientific. Perhaps most problematically, by mashing all the fine details of the incidents into just two variables, I am unfairly making the data fit the Venus hypothesis in some cases. For example, I’ve classified the Othello‘s sighting in the North Sea on 28 February as having a final direction of ‘west’, as the press accounts clearly state that the airship ‘disappeared in a westerly direction’ (Dundee Courier, 5 March 1913, 5). So that’s counted as a data point for Venus in my second chart. But it is just as clearly stated that the airship flew in from another direction (not given, unfortunately) and circled the Othello twice before disappearing to the west. Venus just can’t explain this kind of behaviour, and sailors would anyway be among the people least like to be confused by its appearance.

So these charts are just a semi-quantitative affirmation of my qualitative argument that Venus is involved in the phantom airship scare, nothing more. But there’s a reason why Venus gets mistaken for a UFO to this day.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback: Friday, 19 April 1918 – Airminded

Pingback: Tuesday, 30 April 1918 – Airminded

Pingback: Sunday, 28 April 1918 – Airminded