Today the Glasgow Herald returns to what has been the predominant theme of the last week, America’s increasing commitment to the Allied cause, here represented by a ‘world broadcast’ made by Roosevelt on Saturday (5).

Fearlessly he castigated the Axis partners — “these modern tyrants” with their “stuff and nonsense” about the master race. Their “new order,” he said, was neither new nor order — it was a system imposed by conquest and based on slavery.

Roosevelt says that the Nazis are not looking for ‘mere modifications in colonial maps or in minor European boundaries’; they instead wish to ‘eliminate all democracies’. But they’ve miscalculated, because ‘democracy can still remain democracy and speak and reach conclusions and arm itself adequately for defence’. Presuming referring to Lease-and-Lend, he added that

This decision is the end of any attempt at appeasement in our land, the end of urging us to get along with dictators, the end of compromise with tyranny and the forces of oppression.

Certainly, these are strong words for a non-belligerent.

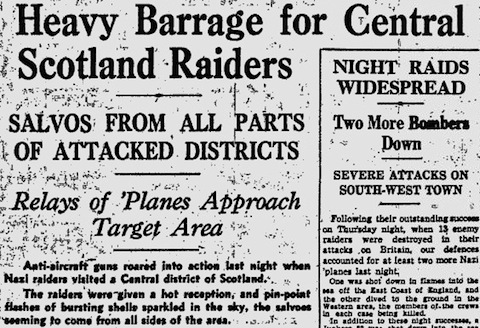

It can now be revealed what every reader of Saturday’s Herald already knew: that the raid on central Scotland the night before was also on Clydeside, meaning it was blitzed two nights in succession. Still, frustratingly few specifics are given of which towns were hit or how much damage was sustained. Instead there are vague descriptions like this one of a destroyed church:

When the German airmen launched their second attack on Clydeside on Friday night they made a church in a residential district one of their “military targets.” They rained incendiary bombs down on what used to be one of the most beautiful buildings in the district.

In fact the Herald, perhaps surprisingly, doesn’t focus on what has been lost (except where churches are concerned; there’s an entire article on that on page 6) but on what, or rather who, has survived. Its main Blitz story opens by describing the ‘amazing’ rescue of Stanley Ewing, a 15-year old boy who was asleep in bed when the tenement he lived in was blown apart by Thursday’s raid. He survived for more than two days and was in good health:

By a remarkable stroke of luck a bag of sugar had been thrown into his bed from a cupboard when the house collapsed, and during his long imprisonment he sustained himself with the sugar.

While the rescuers worked to free him, Stanley told them ‘I’m O.K. When you get me out I’ll tell you where my mother and sister are.’ But the article doesn’t mention what happened to them. Presumably they are dead.

The authorities have arranged transport for people made homeless by bombing to ‘new homes in the country’, particularly on the west coast. At first they are being put up in church halls and the like; then they will be moved to private homes:

Despite the short notice, the evacuees — men, women, and children — fared comfortably, and were loud in their praise of the victualling and accommodation provided. Most of the people have lost everything, and clothing in many instances had also to be provided by the citizens of the burghs.

Jean Kelvin, in the ‘Women’s Topics’ column (7) writes the most effective piece on the Clydeside blitz today. She is proud of the new meaning given to the shipbuilding term ‘Clydebuilt‘: ‘All that it implies in rugged strength and reliability in times of stress has been won by its people this past week’. This she uses to connect Clydeside to the experience of other bombed peoples and to the need to build peace after the bombing is over:

We were now seeing for the first time among our own people what had happened elsewhere. These were the same we had seen in pictures from Spain, from Finland, from Poland. For all their national differences their circumstances were now the same and they had that same look in the eyes — that stunned, numb look. And by the same cause — war. Those of us who remain, no matter how shattered our life’s dream, have that goal to work for that somehow, sometime, so to plan that these ordinary folk in all lands may live the way they want to — in peace.

Of course, peace looks to be some way off yet. The government is about to issue a pamphlet to the public advising them what to do in the event of invasion. In general, ‘stay in your district and carry on’ (4). If you hear church bells, it means that ‘troops have been seen landing from the air in the neighbourhood of the church in question’. Follow orders from police, ARP, Home Guard or Army personnel. Listen to the news and follow its instructions. If fighting is near your home, stay indoors or perhaps a trench, if you’ve made one. ‘Destroy your maps.’

The enemy is not likely to turn aside to attack separate houses. If small parties are going about threatening persons and properties in an area not under enemy control, and come your way, you have the right of every man and woman to do what you can to protect yourself, your family, and your home.

In sum: ‘Do not tell the enemy anything. Do not give him anything. Do not help him in any way.’

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Thanks for posting this fascinating piece of work. Regarding Stanley Ewing, the incident took place at 10 Dudley Drive in Hyndland. You are correct to deduce that his widowed mother, Elizabeth, and his sister, also Elizabeth (aged 21, an ARP telephonist), died in the explosion, along with at least 43 other people.

In Anne Laird’s book, “Hyndland”, the story is also that Stanley survived on sugar, but in her version he had been sent to the front room to get sugar cubes from a cupboard.

Thanks for the additional information, even though it sadly confirms my suspicions about what was being left out of the newspaper account. I suspect people became adept at reading between the lines in this way.

My father was Stanley Ewing. Yes, his mother and sister died in the bomb explosion. I believe that his bed was in the ‘cupboard’ and the shelf above it held the sugar. It wasn’t something he ever talked about – but he would always sleep with the curtains slightly open and I understood this was the reason why.

Thanks, Jane. The bomb seems to have left lasting scars on your father, as you’d expect it to.

The different explanations for the sugar and the cupboard are interesting. 10 Dudley Drive was (and still is) a tenement, so presumably the people living there were poor — hence the bed in the cupboard. I wonder if the confusion arose because middle-class journalists either didn’t understand how the working classes lived? Or maybe they did understand, but didn’t want to confront their middle-class readers with same? Or, of course, the story was just garbled in transmission.

I am a teacher in Hyndland Secondary. Some of my pupils are planning a film about the Dudley Drive bombings. We would love to speak to anyone who remembers the events or who has family members who were involved. If you have contact details please send them to me! My email is NJohnston@hyndland-sec.glasgow.sch.uk

Sounds like a great project! I hope you get a good response; I’ve forwarded your request on to Jane Smith.