The Glasgow Herald, like many early-twentieth-century ‘provincial’ newspapers, made a serious effort to cover war and other international news, as well as reporting on national and local issues. (In fact, it almost seems more interested in what’s happening overseas than it is in London or even Edinburgh.) Its highmindedness is also evident in its lack of interest in trivialities (no sports section today!) and in its rather staid appearance, with the outside pages taken up with classified ads, and the news and editorials at the centre of its twelve page. The Herald might be excused for its old-fashioned look: it was first published in 1783, making it two years older than The Times. (Though admittedly the Daily Mail, a jaunty newcomer, was like this too until the start of the war).

Above is the lead item in today’s Herald, President Roosevelt’s signing into law of the Lease-and-Lend Bill. This will allow (7)

the President to supply Britain and her Allies with almost unlimited supplies of guns, tanks, aeroplanes, ships, and all other war materials and goods.

In fact, he has already begun to do so, approving the transfer to Britain of ‘the first allotment of Army and Navy material’. What this consists of was not revealed, but information from ‘Well-informed circles in Washington’ suggests that it may include ‘Army and Navy ‘planes, flying fortresses, and patrol bombers’ as well as ‘ships, tanks, and machine-guns’. And Roosevelt is asking Congress for another $7 billion to buy more weapons for Britain after that.

This is certainly timely news (though that would probably have been true whenever it came), for the Air Minister, Sir Archibald Sinclair, announced yesterday that while the RAF is already stronger ‘now than when the Battle of Britain began last August’, its growth will be ‘enormously accelerated’ over the next year.He also revealed the existence of two new British aeroplanes, the Beaufighter, ‘for long-range fighter operations and for night-fighting’, and the Halifax bomber, which joins the Stirling and the Manchester as Britain’s heavy bombers:

All three of these have already proved their worth, the first [Stirling] against enemy targets.

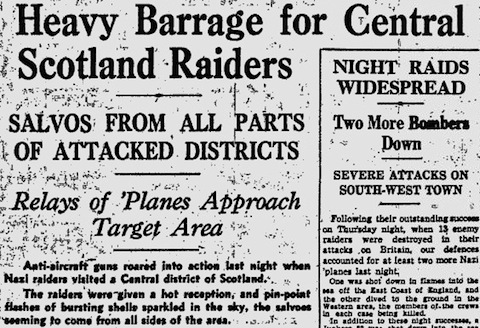

Bomber Command has so far conducted 300 raids on docks and shipping in Germany, 470 [?] on railways and communications (ditto), and 430 on industrial targets (ditto). In his speech before the House of Commons, he also commented on the enemy’s offensive (8):

I will not be optimistic about this menace of the night bomber. I have warned the country, and I repeat the warning, that attacks more severe than any that have yet been experienced may well come upon us. But I know that our methods of defence and counter-attack are gradually improving. Last night we destroyed by fighters and anti-aircraft fire four enemy aircraft and damaged two. As our equipment on the ground and in the air is developed and multiplied, and as our training progresses, we shall extract from the night bombers — as we have already begun to extract from them — an increasing toll.

Sinclair goes on to say that

I will not conceal from the House my own belief that the war is about to enter a grimmer phase. It will be no easy task to defeat Nazi Germany, but it can and it will be done.

Sinclair doesn’t explain why he believes the war will enter a ‘grimmer phase’. His belief in ultimate victory, however, seems to be shared by the Herald, which has begun publishing a series of articles by J. M. Reid on peace aims. Today, in the second of the series, he writes about ‘The gospel of federation’ (6), defined as:

Federal Union — The formation of a super State by the junction of a number of peaceable nations

Reid’s aim is to test this (and in forthcoming articles, other proposals for the post-war order) to see whether, if it were adopted by Britain, it would ‘help us to victory?’ Would it prevent war in future? Would it be welcome ‘to other free peoples as well?’ He notes the basic argument:

If a large number of highly civilised States were united, with a common citizenship, a common army, navy, and air force, a common financial system, and a common government that could deal with their joint affairs, the vast federation would be too strong to be attacked, and it would be impossible for the countries belonging to it to part company with one another when danger threatened, as the League Powers did.

Such a federation would tend to grow over time, accreting other nations until it encompassed the whole world. Not incidentally, this would also lead to global free trade.

But Reid is sceptical of the historical arguments used to justify the idea of federation. The collapse of the Roman Empire shows that it’s not necessarily true that ‘as men become more civilised political units grow larger’.

History suggests that there is a sort of rhythm in such matters, that huge States of conglomerations of States come into existence and break up again, and that civilisation is by no means always at its best when political divisions are fewest.

Germany itself was disunited when it produced Bach, Goethe, Kant et al; united Germany produced Goering and Goebbels (as well as, admittedly, Einstein). Also, Reid argues that the League was not doomed to failure because of the speed of modern warfare.

In fact, preparations for aggressive war on a large scale take months if not years — there was ample warning of Germany’s aggressive policy and even of Italy’s movement against Abyssinia.

So formal federation was not needed then; if the nations had upheld the League’s Covenant, it could have worked.

Lord Rosebery, Regional Commissioner for Civil Defence in Scotland has warned that ‘Objects washed up on the beaches at this time are capable of killing those who handle them’ (5). Anything unusual which is found on the shore should be reported to authorities.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Tis our national newspaper- not provincial at all and older than any newspaper in America.

I used to write for them, on more than the local price of fish!

Sorry, Tabitha, I didn’t mean to imply it was (or is) provincial in the derogatory sense, rather I was trying to show the opposite!

Pingback: Airminded · Friday, 14 March 1941

Brett, you just missed the most appropriate day to cite the Herald. The Clydebank blitz was on the 13th and 14th, though I believe it was censored out of the press at the time.

Pingback: Airminded · Monday, 17 March 1941

Yes, I accidentally started this series a day early, but that turned out to be no bad thing (as far as I’m concerned) because of Reid’s articles about the post-war settlement.