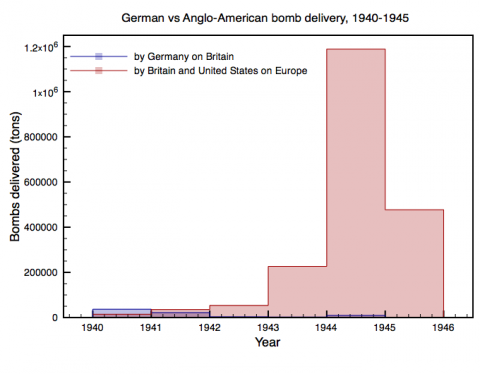

It must be time for some plots. The data here is taken from Richard Overy, The Air War 1939-1945 (Washington: Potomac Books, 2005 [1980]), 120, and represents the bomb tonnage delivered between 1940 and 1945 by Germany on Britain (including V-weapons) in blue, and by Britain and the United States on Europe as a whole (meaning Germany, mostly, but also France, Italy, the Netherlands, etc) in red. The first two years cover the Battle of Britain and the Blitz; the last four the Combined Bomber Offensive. Germany dealt out more aerial punishment than it (or its allies and conquests) received only in 1940; from 1943 Britain and the United States dropped vastly more bombs than the Luftwaffe could ever dream of doing. And here is part of the reason why:

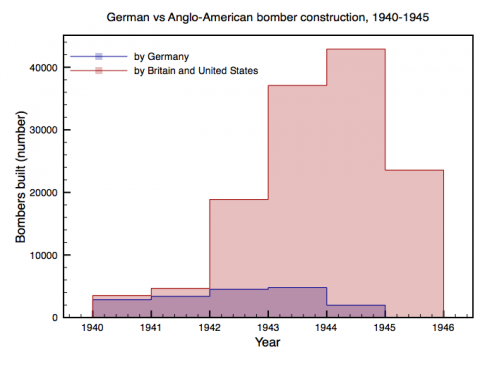

This is the number of bombers built by Germany and by Britain and the United States for the same period, though no data is given for Germany in 1945. I’m not sure if the German numbers include V-weapons this time, and I think the numbers for both sides are for any type of bomber, regardless of how or where it was used. So US Navy dive bombers destined for the Pacific would count, and of course after mid-1941 the Kampfgruppen were otherwise engaged. By the same token, however, a single-engined Stuka carrying less than a thousand pounds of bombs is given equal weight to a four-engined Lancaster carrying 14000 lb, so this plot actually underestimates the true scale of the Anglo-American dominance in the production war.

It all turned out pretty much as ‘Bomber’ Harris told the British public it would, in June 1942:

The Nazis entered this war under the rather childish delusion that they were going to bomb everybody else, and nobody was going to bomb them. At Rotterdam, London, Warsaw, and half a hundred other places, they put their rather naive theory into operation. They sowed the wind, and now they are going to reap the whirlwind.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

The thought occurs that the history of the early 20th Century is basically that of the rest of the world providing math & economics lessons to Germany…

When scientific notation is required to express weapon tonnage delivered by German’s opponents – and just bombs, not total tonnage, at that – neither of the wars Germany started in the first half of the 20th C was Germany’s to win.

Because a touch of hubris can creep into a recitation of these statistics, especially in an Anglo-American classroom, I always add a moral coda too: by 1945, the Allies were capable in inflicting destruction on their enemies which would have seemed incredible at the beginning of the war – but they were also acting in a way which would have seemed unconscionable also.

There’s an interesting note about the Ju 87, in that for the cost of (roughly) a Do 17 or equivalent (a not-very accurate medium bomber) you could get something like 1.7 Ju 87s, which were a lot more accurate.

And accuracy or efficacy (not to mention bomb efficiency) are just two areas where raw tonnage stats are missing a significant set of dimensions. Early war British bombs were awful, items like the cookie and incendiaries have a very differential tonnage – effect relationship to a ‘standard’ bomb, whatever one of those is.

The ‘gee whizz’ exponential relationship of the wind and whirlwind is useful and interesting – more detail would, I suspect increase that disparity.

Allan’s point is an excellent one (as are the others, of course!) and there’s a point that Brett’s thesis touches on – that the public belief pre-war that there was such a thing as a ‘knock out blow’ but where in 1944 that seemed more elusive, despite that huge growth in destructive ability.

Nice graphs, as always!

Although… “I’m not sure if the German numbers include V-weapons this time” – I thought there were tens of thousands of V-1s and a few thousand V-2s? In which case surely there’s no room on there for them…

Hey, Lancs were pretty darn accurate too, when they were flying at 50 feet. (And the tail gunner got to strafe. Bonus!)

And for more detail than Overy can supply, there’s Richard G. Davis, “Statistical History of the Bomber Offensive,” although I’m not sure how you get a copy of it, apart from writing Dr. Davis.

Also, if you’re Corelli Barnett, you can spin the Ju-87/Lancaster comparison in favour of Dr. Junker’s little friend.

Overy’s ‘Why the Allies won’ is also very relevant to this analysis. The allies were able to win because they were able to standardise. This just wasn’t possible in Nazi Germany. I am not, though, in agreement with Alan’s comment that the allies behaviour was unconsionable. I feel this misses the essential point of war which is brutality. The allies needed to do what they could to win and to make certain they won. The alternative would have been too horrible to contemplate otherwise. The bombing of Germany was part of reaching that goal.

I am not, though, in agreement with Alan’s comment that the allies behaviour was unconsionable.

Please read what I wrote carefully. I said that by 1945 the Allies were behaving in a way that would have seemed unconscionable to them six years earlier. I don’t believe that claim can be disputed. Whether or not Allied policy actually was morally justifiable is an entirely different question, and not one that I have the time or inclination to go into right now.

I would qualify your statement very carefully – it was deemed unconscionable in some circles but not in all. One looks at the use of bombing in Imperial campaigns where even poison gas was considered (though not proceeded with). The Soviet Union had no scruples about mass slaughter either well before 1939 as their rather dispiriting record shows. Public statements and more hidden policy considerations differed significantly.

“…Dr. Junker’s little friend.” Let’s be fair that the good (pacifist) doctor Hugo had nothing to do with the Ju 87 (or 88) and was one of the many not in line with Nazi ideology.

No ‘spin’ needed on Ju 87 vs Lancasters – they were different machines of different eras to do different jobs, neither likely to be any good at the other’s primary role.

Davis published one version of his statistical digest of the bombing offensive, which is available here: http://www.au.af.mil/au/aul/aupress/catalog/books/Davis_B99.htm, although it only covers the European war. ISTR that I had to do some trickery to download the spreadsheets of statistical data; I think some of the links were dead. I have copies somewhere, if anyone is desperate and can’t get it to work…

It’s clear that the behaviour of (some of) the Allies in 1945 was of a kind that their own official policy in 1939 would have labelled unconscionable. I don’t think that’s open for debate. What was debated then, was whether the policies and the actions were justified in the circumstances.

For me, the killer fact is that it’s obvious from PREM and AIR papers that the RAF and Churchill were both aware that what they were actually doing (attacking cities) was not the same as the thing that they admitted to doing (‘de-housing’), and indeed, Churchill’s first draft of the Dresden memo made it clear that they were doing one thing under the pretext of doing something else. Thus, it strikes me that consciences were being strained at the time.

As for the graph, yes – although JDK’s point, that weight does not mean damage, stands. Nor does it mean effort – if you were to plot the cost of the resources put in, then the V-weapon blip would be a bulge. A third line might also be added – US tonnage dropped on Japan.

I think that this is a matter of semantics. How do you de-house? You destroy the areas where there are most buildings – that is the cities. Remember that these documents are also being written with posterity in mind. British official papers always contain a certain amount of massaging and gloss. Churchill was able to advocate poison gas to eliminate recalcitrant tribesmen. I am certain that he would have lost no sleep over bombing German cities.

In 1939 there was plenty of speculation about what would happen in a bombing war (much of it exaggerated) and of course the RAF was well aware of how much bombing would be needed (or at least it thought it was). Strategic bombing always involved cities and the policy makers of the day knew this. For the British and the Russians there were no real illusions. Where I think your point has validity is in the American approach which was more delusional – they believed that their bombers were precision machines. Their later actions did not square with the approach they eventually adopted.

Well, the RAF thought they were doing more-or-less precision bombing, too, until the Butt report disproved that in early 1942. Prior to that, they still believed they could specifically bomb, eg. a factory in a city’s suburbs, and of course civilians would be killed as a consequence, but could still be justified according to the prevailing pre-war ethics as collateral damage. But it was a slippery slope. Since area bombing/’de-housing’ was the only choice left (or else scale back the whole bomber offensive, as Tizard argued), a virtue was made of necessity. So there was a change over time; ethical questions in the middle of war look different than in peacetime. I’m with Chris and Alan here.

Lester:

Very good point!

Right now, I’m watching a 1943 film called Bombardier at the moment. It opens with a high-level USAAF debate about whether high-level precision bombing or dive bombing (as the British do, apparently) is the way to go, if the US enters the war. A top secret Norden bombsight (not named, called the ‘golden goose’) is brought out, but we don’t get to see it. Then they have a bombing duel between a dive bomber and a B-17 at 20000 feet. The latter of course smashes the target to splinters. Hilarious!

The problem was the difficulty of accurate navigation and the fact that the CSBS (Course Setting Bomb Sight) was pretty poor. The RAF wasn’t even doing effective area bombing. This actually goes back to the discussion we had on imagination and the conservatism of the British approach. If you watch some of the old videos of British bombers on Youtube you become aware of how often these bombers miss the target which was quite a generous circle (Vickers Virginias flying at 200 feet). There was a fair amount of self-deception about what the RAF could do. In the end the RAF needed to saturate the target to hit it but it is illusory to think that this would have caused any moral problems. If the RAF had realised straight away that area bombing was the way to go they would have done it without hesitation.

The book I remember about the Norden Bombsight was called ‘The Reineman Exchange in which the Americans realise the Norden is not so good and arrange a technological exchange with the Germans via an intermediary. Rather like some of the arrangements that went on in the Napoleonic wars. I remember ‘Bombadier’ and always wondered what the USN and Marines thought about it (the Dauntless dive bomber).

The ethics of killing and maiming people always makes an interesting study.

It seems that in the 1930s the British thought it okay to kill a modest number of civilians by bombing, as long as they were ‘natives’. What wasn’t on was to kill European civilians by bombing.

So, the reasoning goes, we have this ‘bomber doctrine’, that convinces us that huge numbers of civilians will be killed if we use large numbers of bombers. Great! Obviously nobody would do such a thing, so war will be averted. Foreign policy was at least partially shaped by the doctrine, just as it was by mutually assured destruction during the Cold War. (And always is at least partially shaped by military doctrine.)

The foreign policy problem was that nobody else shared their doctrine.

So when war did break out, and especially after the defeat of France, the British had a problem. There were only two ways that they could carry the war to the enemy, and one was killing a lot of civilians with bombs. (The other being promoting resistance movements.) They were too far down that path to turn off it, so bombing the shit out of German cities had to be made to work.

But, as ever when liberal democracies do something shameful, they tended to be rather mealy-mouthed about it. Rather not call a spade a spade, old chap. Churchill certainly understood it, as did most people at the top, especially the top of the RAF. To what extent the full picture was understood through the forces and society is another issue.

Personally, I suspect that the most fervent adherents of bomber doctrine in the 1930s never really quizzed themselves along the lines of: ‘Will we actually do this terrible thing?’ They preferred not to think about it.

Just to finish my mini-review of Bombardier (spoilers!), it was interesting that one of the men had moral qualms half-way through his training (due to the influence of his mother who was in a pacifist group of some sort); his superiors convinced him not to quit by arguing that they wanted peace too, but that bombing was the quickest way to get there. Then there was the climactic night raid, carried out by B-17s against Japan (!). IIRC, only one B-17 had the magic Norden, and was supposed to lead the way and mark the target (named as Nagoya, it looked like only military barracks were shown being bombed). The lead B-17 is shot down, and the others decide they have to switch to ‘area bombing’. But the crew of the pathfinder manage to escape their captors, and one drives a truck through the streets and spreads fire to show the other B-17s where to bomb (and dies heroically in the process). So luckily they were able to carry out precision bombing after all, but it was striking that the possibility of having to resort to area bombing was mentioned at all.

Neil:

Not everyone was mealy-mouthed, Harris himself, for example.

Brett:

In broad terms I take your point about Harris, but it seems to me there’s a little more to be teased out.

Did Harris express enthusiasm for killing large numbers of European civilians in the 1930s? (I ask because I don’t know.) If so, how was he regarded by his contemporaries in the RAF? Presumably, if he openly enthused about such work he was in a tiny minority.

Obviously he wouldn’t be so famous were it not for his role in WWII, but perhaps he wouldn’t have achieved high command at all were it not for the war.

Also, ever since the war, Harris has been an ambivalent figure in British national mythology. His supporters don’t tend to draw attention to his expressed intention of killing as many German civilians as possible.

I don’t know whether Harris said anything about it before the war (will read Probert’s biography of him one day) but I wouldn’t be surprised. He doesn’t seem like the type to hold his tongue. If he did say such things, it didn’t hurt his career either.

“Did Harris express enthusiasm for killing large numbers of European civilians in the 1930s?”

Is that like ‘when did you stop beating your wife’? Harris wouldn’t have ‘enthused’ about such things – the point was it was offered as a deterrent – the bomber as a way of war too terrible to contemplate. If it reminds us of Mutually Assured Destruction’s rhetoric, it should.

The pre-war RAF and airmen were, like everybody else – and right down to today – rather coy about the real effects of bombs*. As has been touched on there was a relationship between weapon and target acceptability from Dum Dum bullets and Gatlings against ‘natives’ circa 1900 to having to carry permission to be equipped with De Wilde bullets when balloon busting in the Great War. In pre-W.W.II Britain, most anything was permissible against natives, but it got more restrictive progressing up from Russians, Eastern Europeans, Italians the French (in their special role of the perennial preferred enemy) and finally the Germans, where gentlemen had investments.

But you didn’t write about it, chaps just knew which chaps were acceptable chaps and which chaps were foreigners and worse. (Civilians were at best undisciplined chaps, and airmen should best shoot and blow up other airmen and their bases and then meet up after the war for brandies, cigars and play by play reviews. Civilians were perhaps rather like crops and buildings – occasionally necessary to destroy, sometimes hit when you were aiming at a chap, but otherwise settled by sending a brace to the local lord afterwards.)

I suspect Harris’ lost-in-the-ether mess Dining In discussions would be illuminating to us and typical for the time. What they wrote or got recorded wasn’t how they thought.

The interesting records in this area are Churchill’s switch from bloodthirsty wartime support of bombing to a politically savvy U turn around the time of Dresden. Harris just never let up from an initial brief on appointment.

*This was also partly because they really had no idea how to bomb, the bombs they had were rubbish, and it was all play acting – sorry, exercises and posturing – sorry, postulating that the bomber would always get through.

Regards,

And because I’m in the National Archives, here’s the smoking gun itself, typed in direct from AIR 19/818. It’s part 98.

CAS. 1075

Circ. PS to S of S

VCAS

DCAS

DB Ops

ACAS(P)

S6

Prime Minister’s

Personal Telegram

Serial No. D.83/5.

General Ismay for C.O.S. Committee.

C.A.S

It seems to me that the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewd. Oherwise we shall come into control of an utterly ruined land. We shall not, for instance, be able to get housing materials out of Germany for our own needs because some temporary provision would have to be made for the Germans themselves. The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing. I am of the opinion that military objectives must henceforward be more strictly studied in our own interests rather than that of the enemy.

The Foreign Secretary has spoken to me on this subject, and I feel the need for more precise concentration upon military objectives, such as oil and communications behind the immediate battle-zone, rather than on mere acts of terror and wanton destrcution, however impressive.

(Intld.) W.S.C.

28.3.45.

That’s very useful Chris, thanks! IIRC, it’s quoted in the Taylor Dresden book along with Churchill’s earlier agenda effectively requiring ‘acts of terror and wanton destruction’.

Despite my having little liking for Churchill, you can nevertheless see this as a pragmatic as well as political decision, and I also wonder if there’s something of a realisation he’d unleashed a monster in Harris’ unbending prosecution of the objective he’d been given – as we know to the exclusion even of sensible short term changes like support for Coastal Command and redirection of bombers to support for the invasion. In an uncompromising war, it’s clear Harris was one of the most relentless Generals – a competitive position, too.

As an aside, it may be a euphemism, but it’s being sold as all about the ‘housing’! Destruction of ‘native’ villages, then ‘Dehousing workers’ then prefabs from Germany for the UK postwar and a few tents for the German prefab makers in the Ruhr… (Pity they didn’t realise it was really going to be all about German cars for Britain’s aspirational middle classes in the latter C20…)

JDK:

To see Harris as a real life General Jack Ripper may be tempting but is unhistorical. By asking about enthusiasm for slaughter, I may not have put the issue in the most felicitous way, but there probably isn’t a very felicitous way to put it. As I noted in my earlier comment, bomber doctrine was all about deterrence. The striking difference with MAD was that it was a dismal failure, (mainly?) because it wasn’t shared widely enough. But there must have been different strands of opinion when it was in place. Somebody must surely have actually been thinking about what it entailed?

My suggestion wasn’t that Harris was ‘like’ Gen Ripper; the critical point was Harris followed – without deviation or moderation and even after he’d been told to desist late in the war – a British policy set for him and that he inherited with Bomber Command. Not that he exceeded his brief, or lost the plot like Ripper. More Sorcerer’s Apprentice than Ripper.

The way Harris used Bomber Command in wasn’t his idea, nor originally implemented by him. He just ensured they got very good at it. So I’d suggest looking to what Harris ‘thought’ about area bombing / ‘dehousing’ pre-war, while interesting, is only worthy exploring with the recognition it wasn’t his choice of action.

While I was being flippant about the ‘chaps’ thinking above, it’s clear there was a huge gap between what they (RAF senior officers, strategists, British Government etc.) thought they could do and what they actually were capable of pre-war. I’d couple that with a common – and down to today – avoidance of the realities of the effects of their action.

Just my opinion, of course.

You’d like to think that somebody inside the RAF was thinking about what strategic bombing actually meant, but it seems not. Scot Robertson’s The Development of RAF Strategic Bombing Doctrine is good on this. The Air Staff used vague terms about objectives such as ‘morale’ instead of things like ‘railways’ or even ‘cities’. (The public line was that Bomber Command would react to an attempted knock-out blow on London by bombing enemy aerodromes and aircraft factories, but I don’t think they had a list of potential targets.) Nor was operational research used to test what ideas they did develop, and the various air defence exercises were generally slanted heavily in favour of the bombers. Only a few years before the war did they start to get their act together, eg writing the Western Air Plans.

I think it’s Michael Sherry (or is it Tami Davis Biddle?) who argues that (the US and UK) national leadership were often far more gung-ho about the use of deterrent weapons than the military themselves, partly because military personnel were more aware of the practical drawbacks of the weapons systems. They were of course happy to rely on the prestige of the deterrent for their particular branch of the services in peacetime.

There are similarities with Donald MacKenzie’s idea of a ‘Trough of Technological Uncertainty;’ those closely involved with a project are less certain about the chances of success than than supporters outside the core group (again because the core group are aware of the day-to-day bugs and issues.) Is there any evidence that the Air Staff were just using the rhetoric of moral bombing? What did your average Flight Lieutenant in charge of a bomber think about the feasibility of their wartime mission?

I agree that the Air Staff had a somewhat less sanguine view of the abilities of a bomber force than their political masters, but it wasn’t by much. They really seem to have had little idea about many of the problems involved until they actually had to carry out strategic bombing (e.g. the need for precise long distance navigation over enemy territory). I tend to think it’s rather the opposite, they thought it was so powerful and so easy that comprehensive preparations weren’t necessary. (Trenchard’s dictum that the morale is to the physical as 20 is to 1 implies that all you really need do is put the bombers somewhere near the enemy and they’ll scare the enemy civilians witless anyway.) The other option is that the Air Staff were simply incompetent, but their far more impressive performance with regards to strategic air defence suggests that that would be unfair (and this in turn would be for the same reason: they overestimated the power of the bomber and so exerted great efforts to defend against it). It all goes back to the Gotha summer of 1917 of course …

Someone should write an institutional study and/or collective biography of the Air Staff between the wars. I’d read it, anyway.

Brett:

Thanks for the tip about Scot Robertson’s book.

JDK:

Sorry, I didn’t mean to connect Jack Ripper with your comments. I was just rather clumsily musing.

The whole development of bomber doctrine and policy seems bizarre. As far as I can see it has two vital chunks missing.

The first is the answer to: ‘How do we do this?’ It seems that the Air Staff always saw doing it as so straightforward that no research was necessary.

The second would be prompted by: ‘What happens when we actually do it?’ To a certain extent, the reason that they didn’t get to asking that would be because they didn’t even get to the first question. But only to a certain extent.

In this country, the prime minister and some senior cabinet ministers have to write down their thoughts about the use of the nuclear deterrent as soon as a new government is formed. Presumably something of the same happens in other nuclear powers. I know the parallel is far from exact, but I’m really struggling to accept the idea of faith in a decisive weapons system not being accompanied by or qualified with any discussion of consequences.

Using nuclear weapons is so obviously a single-point, irrevocable decision, that it’s very hard to set up a system for it without thinking through the consequences. This is especially the case in states (like the UK since the mid 1990s) whose only nuclear weapons are strategic ICBMs. Conventional bombing of the WW2 kind – even for the advocates of the KOB – is still remarkably incremental and recallable. Perhaps that’s why the only historical decision to use nuclear weapons was made in a complex and unclear way: it had to relate to exising bombing policy.

Hi Neil,

No problem! I’m no expert on Harris, but it’s clear even to me that he was a far more complex character than the cardboard figure offered up by both sides of the Bomber Command’s debate, so I was trying to be very precise. Hope I wasn’t wrong!

I think Brett’s put his finger on the answer to what they did think/talk about – it was morale, with a very strong subtext of the British moral fibre was better than any foreigners, so we knew who’d win that one. If expected to be specific, they tended to talk about ports, bridges, airfields, factories and ‘fuel dumps’ etc, but its evident that in most cases they’d never actually thought about how to knock even these obvious targets out. The actual failures of bombing – even when they achieved expected accuracy – early in the war is clear evidence of that. There’s an interesting article in Flight in 1936* that postulates a lot of this with a fictitious air war – obviously it’s press and for the public, so there would be a degree of euphemism, but I don’t think even the most aggressive RAF airmen would think about rending people limb from limb or cooking them – and even less likely to think of civilians in that context.

Jakob asked “What did your average Flight Lieutenant in charge of a bomber think about the feasibility of their wartime mission?”

From my researches for the Aircrew feature in Aeroplane, where we’ve covered the Hawker Hart, Handley Page Heyford and pre-war Bristol Blenheim, my impression was that it was a mixture of very sophisticated and somewhat dangerous sport (rather like jousting) coupled with the best flying club in the world (with the coolest toys) and a chance to look dashing. Beyond the regimented and rigid tasks they’d been set in training or for competition or unavoidable tasks (like converting from the simple Hart to the twin-engine, VP-propped, retractable-undercarriage and flap-equipped ‘fast’ monoplane Blenheim) there wasn’t a lot of thinking going on, witness the difficulties in changing landing techniques from Hart to the Blenheim; where the incentive wasn’t even staying alive, but was ‘acceptable technique’ as seen from the Officer’s Mess.

We know there were competitions for bombing, actual occasional bombing exercises carried out and navigational exercises over well-lit peacetime Britain and France, but the many clues to performance shortfalls were either not evident (they didn’t realise the full-size bombs were useless because their destructive effect was never tested, and they mostly used light practice bombs) or ignored or written out by the ‘rules’ of the wargame.

All of this was hidden well into W.W.II for the majority by the public perception of bombing being an effective weapon by the press’ PR, and I’d assume that the majority of early war recruits flying in four-engined heavies in 1943-5 (and by then establishing a very technically adept approach to delivering large loads on target) never realised how much the early war pilots work by guess, God and luck. And those surviving old hands probably wouldn’t talk about it, even if they’d realised they were part of the high percentage missing all their targets as highlighted in the Butt Report (notably not an RAF document or RAF evaluation of efficacy).

Finally, Jakob also asked “Is there any evidence that the Air Staff were just using the rhetoric of moral bombing?” and I’m wondering whether he meant ‘moral’ or ‘morale’ in this context, as both have an appropriate but different meaning in this discussion and context – not talking about killing ‘innocent civilians’ or ‘breaking the enemy’s morale’.

Which is another pair in a very interesting set of questions.

*25 June 1936 “If, 193-?” by H.F. King.

‘Moral’ was an alternative (and before 1925 or so, the more common) spelling of ‘morale’. It’s really annoying, actually, particularly since moral questions (modern spelling!) do indeed come into it!

So all we need to know is if Jakob’s using a pre-1925 web browser? Is that Steampünknet? (With Umlauts on top, please.)

JDK: I meant ‘moral’ in the Trenchardian (i.e. ‘morale’!) sense; were the Air Staff overemphasising the likelihood of an enemy’s morale collapse due to bombing for reasons of institutional influence and prestige? From what Brett has said, this seems not to be the case; they genuinely believed that this was a war-winning strategy.

On the morality of bombing, I don’t know whether the Air Staff ever made arguments in these terms. Airpower enthusiasts did make the argument that the bombing of civilians would shorten wars, leading to a net reduction in casualties overall. Presumably if any thought was given to the matter at all, it was rationalised in terms such as this. Was there, for instance, ever any discussion in the Royal Navy about the morality of blockade? A quick google suggests that civilian excess mortality in the First World War due to blockade was c.750’000, which is comparable with deaths due to strategic bombing in the Second World War.

On the other hand, the excess deaths in WW1 could be blamed on the German government for mismanagement (of which there was quite a lot, especially in 1916/17), or spending the resources on guns rather than butter. There’s a degree of plausible deniability when starving people though a blockade (see Iraq, 1991-2003) that you don’t get when you start issuing orders like “4. Objective: destroy HAMBURG”

To take this in a slightly different direction:

Harris followed – without deviation or moderation and even after he’d been told to desist late in the war

After reading Mark Connelly’s account of this, I’ve been persuaded – and I wonder if anyone else has been also – that Portal should have sacked Harris in the autumn of 1944, and that his unwillingness to do so represents a serious failure of command. This isn’t so much a point about Harris’ tactics as it is about his insubordination; once it became clear to Portal that Harris was wilfully refusing to obey his orders to prioritize oil and transportation targets, Portal should have replaced him. As it was all he did was make some weak remarks about a difference of opinion and the judgment of history.

My source for that very same opinion is Max Hastings’ _Bomber Command_. I was convinced by it, but not quite ready to hold it on Hastings’ word alone, even if he dad did work for the _Eagle_. It seems pretty reasonable.

I changed my mind a bit on the dismiss Harris front having heard Sebastian Cox talk about the issue. From memory, his argument was that the percentage figures used to suggest that Harris ‘disobeyed’ orders are a bit misleading and that, although he initially disputed the _directive_ that he should turn to oil and transportation, Harris did alter BC’s attacks, as far as he could, when he was actually ordered to do so. For all the navigational and aiming improvements of the later war, weather remained the key determinant of what bombers could hit, and Harris’s orders (appropriately) allowed him to make operational decisions about how that played out in terms of targets. Again this is from memory, but I think Cox looked at the number of times at which weather made more precise attacks possible over the winter of 44-45, rather than just the percentage of total sorties flown, to argue that Harris did as he was told, including reverting to city attacks when that was all that meteorology would allow. He also made the point that, to a degree, what you call your attack is what it becomes – attacking transportation by hitting key rail hubs still meant hitting cities/destroying cities with rail hubs in them hit transport. That is not to say that Harris was a pleasant man, that bombing was moral, or that there were not other reasons besides the weather that he was disinclined to attack oil and transport. But for me Cox made a good case that you can’t get him for disobeying orders. This might be in Cox’s introduction to Harris’s Despatch, but I’m away from my copy at the moment and can’t check. And I might have been so distracted by discussion of heavy rock umlauts elsewhere on this blog that I’ve misremembered the whole thing, in which case grateful to anyone who corrects me.

Fascinating, Dan, thanks.

Great, so in order to be fair-minded, now I have to read another bloody book … gee, thanks, Dan ….

;-)

I know, it’s just one damn thing after another, isn’t it. Will try to find out exactly _which_ book for you next time I’m in the office.

Ironically, Trenchard — roughly speaking, WWI’s Harris-analogue — was also criticised for ignoring targeting instructions from his superiors, but in his case he wasn’t supposed to be going after transportation targets!

But there’s also an exchange with Weir in which the Minister says “Couldn’t you try to kill Germans? It’s the only language they understand” and Trenchard replies “Don’t worry, we may be aiming at railway stations but most of the bombs miss and kill civilians.” It’s in Boyle’s biography of Trenchard.

Simplistic maybe, but I would’ve though Germans would understand German, while dead people are notoriously undemonstrative in comprehension tests.

Relating to what bomber leaders ‘talked about’ (and what they chose to ‘overlook’) I just came across this quote on LeMay:

Richard Rhodes on LeMay’s Vision of War

“…and simply take out the whole country at once. Nowhere in the documents that discuss these plans is there any discussion of the fact that you would kill 250 million people when you did that. That was just one of those collateral damage effects that you didn’t discuss when you were laying such plans.”

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/bomb/filmmore/reference/interview/rhodes07.html

Having just found this thread and the discussion on Harris, I must mention the political and social climate from which Harris came. He was an Edwardian, of a class that saw itself as both leaders and innovators. He was from the sub group of the class that were technically minded.

He became a junior bomber commander in the Great War and was greatly influenced by his experiences. Along with all other Air commanders of the 2nd World War he was aware that the next war, when it came, would be about blood and guts attrition. Not a popular concept with a war weary nation.

The Air staff in the period 1919-1935 had great difficulty keeping a regular supply of aircraft production manufacturers in being as they would be the bedrock of an air force expansion. That they succeeded is evident in aircraft from the Avro Lancaster to the Vickers Wellington.

The 10 year rule was often used by politicians to defer defence budget expenditure (there wasn’t any votes in it) The vote of 1935 finally gave the RAF the required finance to expand, despite being rejected by the House of Lords. That the Air staff went for quality over quantity is something we must all be thankful for.

The pre1937 structure of the RAF could appear confusing to researchers today as to what it was for, but the overiding aim of the RAF from its inception was to take the fight to the enemy, that meant bombing.

The 1937 restructuring, whereby seperate RAF commands came into being was an organisation that lasted well for the next 30 years. And as any erk would tell you. As part of the RAF history lessons was the structure of the RAF and the Order of Precedence of the Commands, Bomber Command was the premier Command, always. Fighter Command was 2nd. The initial numbering of Groups reflect this.

Much of this was overseen by Newell, a much overlooked CAS. So Harris taking over the premier Command gave him unprecedented influence in the corridors of power, Portal as his nominal boss would have had to tread lightly. The British do not sack senior officers. It could be said the Harris had much in common with General Montgomery, they were both ‘awkward’ characters.

Churchill of course when changing his views on the strategic bombing campaign no doubt had his eye on the General election that would follow the defeat of Germany.

To take just one point from an interesting post:

The British do not sack senior officers.

Ironside? Wavell? Auchinleck? Admittedly the British don’t do anything as vulgar as sack their senior officers: they give them a peerage and boot them upstairs, preferably to some grand and distant outpost. I don’t think there’s much doubt that if Montgomery had lost the favor of his political master he would have been just as summarily replaced. Even his promotion to field-marshal (along with his relegation to army group command) in the autumn of 1944 was a kind of genteel sacking.

It’s interesting that in the Rhodes interview linked to by JDK above he mentions that LeMay was trained as a civil engineer (as indeed was Leslie Groves,) who treated war as an engineering problem. This seems to me to be a defining characteristic of modern industrial/total war; any conflict involving mass armies and mass production of weapons is going to rely on some kind of cost/benefit analysis, even if it’s only ever made implicitly.

In a related vein, Zygmunt Bauman’s brilliant book ‘Modernity and the Holocaust’ argues that the extermination of the Jews was not a throwback to barbarism, but rather closely linked to modernity; The Final Solution employed an impartial bureaucracy, division of labour, and used cost/benefit analyses to organise genocide. (He also explores the ‘rational/scientific’ basis of this kind of murderous anti-semitism.) Crucially, moral judgments on the part of the perpetrators are replaced by bureaucratic rule-following; success and failure are defined by reference to the metrics set by the bureaucracy. It is no surprise that ‘I was only following orders’ became the Nuremberg defence.

One could apply Bauman’s analysis to projects such as the strategic bombing campaign and the development of atomic weapons, and from the discussion above I think you’d find a similar concentration on process rather than overall morality; in some ways it would be more surprising to find extensive ethical discussions taking place.

Alan Allport is right to expand on the sacking of senior officers, once they reach the higher ranks of command they’re moved sideways rather than demoted. It is not what I would consider a proper sacking.

At General Staff level their job would involve an interface with politicians, which allows them to plot, scheme, dish the dirt etc, aimed at advancing their own position up the slippery pole. Montgomery was extremely good at this. He did for a number of careers of junior generals, and perhaps his biggest scalp on the way to the top was his demolition of 1st Army’s General Anderson.

This all by the by – In Harris’ case he was seen to have the right qualities of drive agression and competence to Command BC by both his peers and the politicians.

Portal by contrast had much the same qualities as General Alexander. He was more consensual by nature. His was the guiding hand for the Air Force as a whole, so a disagreement with Harris would not be unusual. This also applied to other Commanders. It should be understood that when conducting a war the top brass work as an argumentative committee, each with their own fiefdoms agenda to be promoted.

@Jakob – would be interesting to take your point back beyond WW2 to look at the planning of the blockade before WW1, as covered in A. Offer’s The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation (Oxford, 1989).

Jakob:

Interesting — Tooze’s Wages of Destruction would be another slant on the same topic. But it would only apply during wartime. Before then there wasn’t even much thinking about process, beyond

1. Build some bombers.

2. ???

3. Profit!