And marble, and granite, and wood …

I wrote recently that every town in Australia seems to have a war memorial. Here are some examples, photos I took over a three day period without going too far out of my way. This post is image-heavy, but everyone has broadband now don’t they?

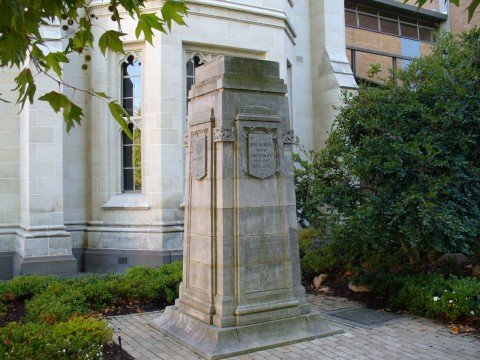

This first one is an obelisk at the University of Melbourne. It’s tucked away in a shady corner of the South Lawn between Wilson Hall and the Old Law Quad. Probably, few people even notice it.

The inscriptions are entirely in Latin, which is unusual but presumably is intended to reflect the educated status of the University’s staff and students who fought in the world wars.

The inscriptions on the four faces read:

DE IMPERIO

DE PATRIA

DE ACADEMIA

BENE MERITIS

DOMI

MILITIAEQUE

1914 1918

1939 1945

A free, very rough and likely very wrong translation based upon my schoolboy Latin and my Googling skills might go something like this:

from the Empire

from the Dominion [or: their homeland, fatherland]

from the Academy

they served [or perhaps: they gave]

at home

and abroad

1914 1918

1939 1945

Anyone with more Latin than I, please help out!

I can’t find anything about this memorial on the web, though I did find that there’s another one on campus which I could have looked at. It’s a series of stained glass windows and two tiled tablets, erected in 1920 to commemorate the war service of the staff, students and alumni of the Melbourne Teachers’ College, which later became part of the University (the building now houses the School of Graduate Studies).

Next is an interesting, and I think unusual memorial: a statue of the goddess Peace in a small roadside shrine, backed by a grove of trees. This is the Honor [sic] Reserve in Snake Valley, a small town (population about 350) west of Ballarat in country Victoria.

Less Latin here, as you might expect, though there is some (‘PRO PATRIA’, for the homeland) and of course Peace was a Roman goddess. Despite that, the inscription has a Christian flavour:

To the Glory of God

and in Honor [sic] of the Men

of this District

who fought in the Great War

1914-1918.

The names of those who served are arrayed on both sides of the shrine.

The local branch of the RSL closed down a few years ago, and the task of maintaining the memorial fell to the Snake Valley Historical Society. They’re trying to set up a separate organisation to deal with the task, as this will make it easier to attract funding. I wish them luck, it’s a beautiful little shrine and ought to be well-cared for.

The war memorial in North Melbourne, one of the inner suburbs of Melbourne, is more typical of local community efforts at commemoration. A simple obelisk, with the ANZAC crest, and the following inscription:

IN IMPERISHABLE MEMORY

OF AUSTRALIA’S SONS

— WHO DIED —

IN THE CAUSE OF FREEDOM

IN THE GREAT WAR

1914-1918ERECTED BY THE MEMBERS

OF THE NORTH AND WEST

MELBOURNE RED CROSS SOCIETY

ON BEHALF OF THE CITIZENS.

The other sides list the major theatres where Australians fought in the First World War: ‘GALLIPOLI’, ‘FRANCE’, ‘PALESTINE’. Much more modern plaques list other wars Australia was involved in: the Second World War, Korea, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesian Confrontation, Vietnam.

Unfortunately, as these photos show, the North Melbourne memorial is not situated in a tranquil location, suitable for introspection on the sacrifices made: it’s squashed into a triangle of grass, with busy roads on two sides and car parking spaces on the other. On the other hand, it is at least in the heart of the suburb, at the other end of the main street from the old town hall.

The Australian Hellenic Memorial is in Melbourne. It’s also in Canberra, or at least another one with the same name is, which is a bit confusing. I think the Melbourne one may be specifically for those who died (both Greek and Australians) in the Greek and Crete campaigns in the Second World War. I assume Melbourne got its own because of its strong ties with Greece through immigration after the war — it was conceived and constructed some time within the last decade.

Presumably there is some heavy classical allusion-making going on here. The upright columns evoke a Greek temple. I’m not sure about the urn and the rough-hewn rock with the temple-shape on top — an acropolis perhaps?

I’d forgotten about this next one (and the last one too for that matter) — I stumbled across while walking to the Shrine of Remembrance. It’s a memorial to the Victorian casualties of the Boer War, or South African War as it was then known. Unlike the uniformly classical designs of the post-First World War monuments, it’s a splendidly Gothic … whatsit. I’m not sure what the correct architectural description is! Like the Australian Hellenic Memorial, it is in the King’s Domain in the heart of Melbourne.

‘KING AND EMPIRE’ — my guess is that such a phrase would have been easier to use, less hollow, in AD 1903 than in AD 1919.

Unlike the other memorials here, this one was raised by the returned soldiers themselves, not their community:

ERECTED by Members of the

5th VICTORIAN CONTINGENT, V.M.R.,

in memory of their

FALLEN COMRADES in South Africa, 1901-2

I’m surprised that there were so many Boer War memorials — a probably incomplete list is here. On the other hand, it was Australia’s first war, after all — the Commonwealth of Australia came into existence during the war, in fact, while units from the various colonies (like the Victorian Mounted Rifles) were already over there fighting for King and Empire. So perhaps I shouldn’t be too surprised then. But it’s certainly been replaced by the First World War in Australia’s founding myth.

I’ve been going through the list roughly in ascending order of size. And now the monuments are starting to get appropriately monumental in scale. This is the Arch of Victory at Ballarat, a classical conceit if ever there was one. The Arch was completed in 1920. Oddly, the end date given for the war is 1919. My guess is that this refers to the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed in June 1919.

It’s also unusual for a war memorial to unashamedly proclaim ‘VICTORY’ like the Arch does …

… but this bombast is more than compensated for by the Avenue of Honour which starts from the Arch (which I was standing under when I took the above) and extends for 22 km. It is flanked on either side by a rank of trees, over 3300 in all. In front of each tree is a plaque (only barely visible in the photo, unfortunately) with the name, unit and number of a man from the Ballarat region who served in the armed forces in the First World War. It really is a dramatic and imaginative form of memorial, and it inspired over a hundred similar avenues in Victoria and the rest of Australia. It’s not, however, a uniquely Australian phenomenon, as I have seen claimed: there’s at least one in Canada, and they were quite popular in the United States after the First World War too. And it looks like there’s one in Leeds. Still, the Ballarat Avenue of Honour must be one of the longest and best-preserved in the world. (Another form of living memorial is noted at Trench Fever.)

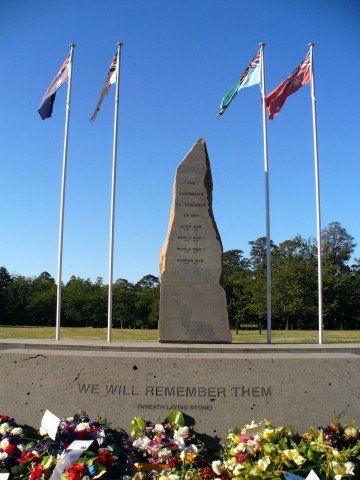

Another Ballarat memorial, though this time it represents men and women from across the country: the Australian Ex-Prisoners of War Memorial. More than 35,000 names (including my great-uncle’s) are etched on two black granite walls, separated by six obelisks which bear the names of the countries where they were held, from the Boer War to Korea. Another is lying as if it has toppled, I suppose to represent those who died in capitivity (over 8000, mostly in the Second World War). The photo at the top of the post also shows the obelisks.

The day that I visited was by chance the same day that the annual ceremony was held, the third since the memorial was opened in 2004, which accounts for all the wreaths.

Last of all is the grandest of all, Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance.

As can be seen, it’s big. And once more, it’s classical. In fact, it’s inspired by one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. It really is a very impressive building, easily one of the largest war memorials in Australia — second only to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. Not that size is everything, of course … but why is Melbourne’s so big? K. S. Inglis, in Sacred Places: War Memorials in the Australian Landscape (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2005 [1999]) suggests that it’s partly because Melbourne was at the time of the Shrine’s construction (1928-34) still the de facto capital of Australia: Parliament only moved to Canberra in 1928, and most of the civil service remained here until after the Second World War. It may also have been a harkening back to the “Marvellous Melbourne” days of the late 19th century, when many grand structures were built. Finally, Inglis suggests that the influence (and interests) of Sir John Monash, a Melbourne-born civil engineer and the successful commander of the ANZAC Corps on the Western Front, played a part.

The inscription reads

THIS MONUMENT WAS ERECTED BY A GRATEFUL

PEOPLE TO THE HONOURED MEMORY OF THE

MEN AND WOMEN OF VICTORIA WHO SERVED

THE EMPIRE IN THE GREAT WAR OF 1914-1918

It still serves this function of a place of memory. Every year on ANZAC Day, a dawn service is held at the Shrine. Ten or twenty thousand people gather to shiver in the cold and to hear the Last Post being played. I went a few years ago, and it’s a very moving experience.

The winged woman here is the Mother Country; the tympanum as a whole depicts “The Call to Arms”. (The tympanum on the other face shows the Homecoming.) From her vantage point, she can see down St Kilda Rd, across the Yarra and down Swanston St into the heart of the city.

I think that’s enough for now — I have more photos from the Shrine area, statues, the Second World War Forecourt and so forth, which I may work into a post at another time. But hopefully I’ve shown something of the ubiquity and variety of Australian war memorials, and the ideals and values chosen for comemmoration — peace and victory, King and Empire, country and comrades.

For more information, see Inglis’s book, or the War Memorials in Australia site, if it ever comes back up.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

It’s interesting that Australian memorials seem to emphasise those who served, not just those who were killed. Most memorials in Britain are only for the dead, and the CWGC memorials on the battlefields are only for missing men who have no known grave.

It’s not unusual for Versailles to be taken as the official end of the war. The British Victory medals carried the dates 1914-1919 (although it could also be awarded for fighting in the Russian civil war!).

This post has made me realise that I have absolutely no idea where my village’s war memorial is or what it looks like! I must have seen it loads of times but ironically have no memory of it. The one in the next village along is curiously situated in a lay-by on the wrong side of the by-pass. The site was an airfield in WWII (home of 100 Squadron) so it might be specifically for WWII airmen – I’ve never had a close look at it.

This is a fascinating post. I believe that memorialisation is a much under researched aspect of military history. The manner we remember our war heroes reflects the very fabric of our society.

In his book The Last Great Quest, Dr Max Jones writes about Captain Scot. He devotes part of the book to the manner in which his ‘heroic’ death was remembered. He explains that at the time memorialisation was moving away from realistic and statuesque representations to more a simple and symbolic memorial. He argues that this was in line with French thinking of the time. Jones suggests that the lack of a body for burial was key to the way Scot was remembered. He also suggests that when the First World War broke out, and very few bodies were returned to British soil for burial, the manner in which Scott had been memorialised set the standard for First World War remembrance.

Gary Smailes

Gavin:

If I had to guess, I’d say the memorials for those who served reflect the fact that all Australian servicemen and -women were volunteers and not conscripts. This was a source of both pride and division (there were two bitter referendums on the issue during WWI and the PM was ejected from the Labor Party because he wanted to bring in conscription). With the war over, I can certainly see communities wanting to emphasise the fact that we didn’t need to resort to compulsion (unlike most participants, I think), but also maybe taking the chance for some political point-scoring against those who campaigned for conscription.

I did think of Russia as a possible explanation for the 1919, but as far as I can tell, Australia did not officially take part in the Allied intervention. It might have done so in ways other than committing troops, and individuals may have served in the British force. So it might be possible, but Versailles is probably more likely.

And it is odd how these objects can remain invisible, even in places you know well! My brother didn’t know about the memorial in his town. For that matter, I can’t recall the war memorials in the various towns where I’ve lived, it’s only fairly recently that I’ve kept an eye out for them. And I’d be willing to bet that most of the thousands of people who drive past the North Melbourne memorial every day don’t even realise it’s there.

Gary:

That’s interesting. Of course, the bodies of Australian dead were not returned to their homeland either, so that explanation could equally apply as well. I don’t know if the Scott case would be as relevant in Australia though — as you can see, the Boer War memorial, which predates Scott, is already very abstract, though certainly more ornate than most of the post-WWI ones. But I can’t really generalise from such a small sample.

I’m sure that there were Aussies in Russia in 1919-20. I remember flicking through a book on the topic once.

ObMemorials: in this case are two that I noticed yesterday, one that’s got an online picture:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:VictoriaParkLeicesterMemorial.jpeg

and a rather smaller one just down Peace Walk from it, dedicated to three local guys who died fighting in the Spanish Civil War. CPers, but hey.

OK, here’s the straight dope, from Jeffrey Grey, on Australians in the intervention in Russia. No Australian units fought, but a few hundred Australians served in British units for a variety of reasons. As they did not attract much attention at home, it’s probably unlikely that memorials would refer to them. Having said that, because memorials were generally raised locally, the effect of local circumstances and personalities might conceivably alter this conclusion. But I’m sticking with Versailles!

The conscription/volunteer distinction for the difference between British and Australian war memorials is mostly right, I’m sure: much harder to commemorate all who served if some went unwillingly – although given the war/post-war renegotiation of ‘citizenship’, that might still have occurred in some places, and church rolls of service in particular served that function. I have only ever seen one stone memorial which recorded all those who served – in a Derbyshire village near Bakewell. In small communities, I suspect that the issues of service could sometimes be more easily negotiated.

On the later use of war memorials – it’s interesting to note how the London Cenotaph has become a memorial for all British conflicts. There’s correspondence in the PRO from the 1950s between a bereaved mother and the Home Office, where they tell her she can’t lay a wreath officially because her son died in the Korean War, and the Cenotaph is just for the two world wars.

Thanks to the National Inventory of War Memorials I’ve located our war memorial. It’s a stone cross in the churchyard, which probably explains why it blends into the background. It’s still quite pathetic that I have to look on the internet to find out about where I live!

I was also shocked to discover that the recently erected memorial to the crew of the Lancaster that crashed in the village in 1943 apparently cost £130,000!

I also did some follow-up research, namely buying a little book on campus architecture from the university bookroom (which I’ve had my eye on for years but never actually got around to buying before), which has a little bit about the University memorial. It dates from 1925 and was designed by an architecture student, to commemorate the 1725 former students who served in WWI (of which 253 were killed). The Latin inscription is partly translated as “To those who deserved well in war and peace”, which doesn’t sound quite right to me … but whatever. It was modified and updated after WWII. Interestingly, it was originally in a more prominent location, in line with the Grattan St gate and the Law Quad, where it couldn’t be missed. I wonder why it was moved — for obstructing the flow of pedestrians? Doesn’t say when the move took place, but if it was the late 1960s/early 1970s I could imagine it was as a sop to the Vietnam War protest movement.

Of relevance to this post, this evening I went to a most informative talk by a fellow student, Michael Taffe, who did his honours thesis on Victorian avenues of honour, of which the one in Ballarat is the biggest and best known, but wasn’t the first. He’s found well over two hundred of them (the previous best estimate had been about 90), and there still coming in. Lots of them are being cleared by local councils to make way for developments or because the trees are dying etc, but in most cases the very fact that there was an avenue of honour there has been forgotten. Michael’s argument was that the avenues were very different to the stone memorials which are more familiar now, since they were living memorials — they celebrated life. The inaugural ceremonies were much more festive occasions.

Also, he mentioned equivalents to the avenues of honour overseas — apparently they were hugely popular in the US (4000 was the figure, I think) and Canada, though they’ve fared less well than the Australian ones. (He also knew of one in, I think, Nottinghamshire.) It’s unclear whether there was any connections between the different countries — whether the idea started in one and spread to the others, or whether it was an idea that was in the air. But the Australian ones seem to date to 1916 (for the first ANZAC Day) which would be before the American movement, at least.

Michael’s working his research into a publication, so I’ll have to keep an eye out for that.

Nice to see my research has reached a wider audience, I saw a publisher socially laat evening and hope to have thesis and wider research in publishable form early 2009. Aiming for release June 2009. Very exciting to get to this stage even –

Michael Taffe

That’s great news! Congratulations. Please drop me a line when it’s published.

There is at least one avenue of memorials Oaks in NZ

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/maungaraki-war-memorial-gladstone

The register doesn’t have another semi-example – the town of Hawera has individual trees in a grove dedicated to specific veterens.

BTW, info on NZ Boer war memorials at

http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/war/war-memorials/south-african-boer-war-memorials

My Latin has got a bit better now. My best guess is:

“To those who served the Empire, homeland, and academy well at home and abroad”

Mereo is a strange verb as it has active and deponent forms which mean the same thing.

And congratulations Michael!

Brett, check your comment spam queue (too many links, I guess).

I’ve since remembered another memorial avenue, between Takapuna and Devonport on Auckland’s North Shore.

Interesting! I remember querying the 1919 date as a kid; my understanding is it relates to the formal end of the war at Versilles, rather than the armistice which is when the fighting stopped (but not the war). I think a good deal of effort was put into ‘forgetting’ the Allied intervention in Russia, as well.

Another reason as to the different commemorations between the UK and Australia will maybe be numbers – the sheer numbers of the British population that served was huge (as was the death toll) as against the large number of Australians, will have mitigated against those lists of ‘all’ in the UK.

As demonstrated by the CWGC, it’s much easier, or more practical, to keep tabs on those who died, rather than those injured or serving. It’s notable that Australia has the online Nominal Roll listing all that served, while Britain doesn’t have a direct equivalent, but the CWGC list all those (inc Australians) who died – officially.

There are numerous organisational memorials in the UK at collages, universities, schools and railways among others that often list all those who served as well as all those who died.

Having travelled in the UK, Canada, New Zealand and Australia, Canada seems the odd one out in not having so many physical public memorials as the others – but that might just be my impression. Certainly there are plenty of other acts of memory there!

And, as far as I know, only Australia has a museum cum memorial; all the others have museums and separate memorials.

Regards,

And, as far as I know, only Australia has a museum cum memorial; all the others have museums and separate memorials.

It so happens that I was in the Auckland War Memorial Museum yesterday. Features include the Cenotaph on the forecourt, and the Rolls of Honour taking up much of the third level (as well as maps of theatres of war, and a blank section of wall marked with ‘May these panels remain empty’). This is strictly speaking for Auckland Province only.

http://www.aucklandmuseum.com/?t=10

The NZ National Memorial was recently given more prominance with the return of the Unknown Warrior – this is outside what was the Dominion Museum in Wellington

http://www.rsa.org.nz/remem/unknown_warrior.html

http://www.khantazi.org/Events/Carillon/Carillon.html

Thanks Errol. It’s the danger of trying to be definitive! Clearly the Auckland War Memorial Museum is fulfilling a very similar niche to the Australian War Memorial.

Gavin:

Somebody’s been improving himself! Thanks, that sounds more plausible than the translation I found (though maybe ‘deserved’ was a typo for ‘served’).

ErrolC:

Fascinating. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of (or heard, for that matter) a carillon before. There’s another war memorial carillon at the University of Sydney.

JDK:

I was certainly struck by the apparent lack of a memorial aspect to the Imperial War Museum when I was there last year. I more or less was expecting it to be something like the AWM. But I had to reconsider that after reading a 1920s article arguing that the IWM was serving, or rather would serve, a memorial function by showing people who had a personal and often deeply sorrowful connection to the war just what it had been like. I suppose that idea is still there, though as time passes it has tended towards a more or less pure museum.

Good points about the forgetting of the Russian intervention and the space required to chisel in the names of everybody who served …

Merere can mean “to deserve” on its own, but the phrase “bene merere de…” means “to serve well” or “to do service to”.

There’s a memorial carillon up the road from me in Loughborough (pronounced ‘Low-brow’ owing to the intellectual focus of its university’s undergrads).

http://www.loughboroughcarillon.com/

Surely it can’t be too different to that of any other undergraduate population!

Jocks. Loughborough used to be the national Physical Training College, and they still have great facilities which means that a large proportion of the undergrads are there because they are into sport rather than curious about anything.

ObHistory book that nobody’s written: the massive social division in the UK undergraduate population of the 1950s between the ‘hearties’ and the ‘intellectuals’.

BTW, Canberra has another Carillon, on Lake Burley Griffin, the bells coming from Logie Brogie. Hem, sorry, Loughborough. ;D

http://www.nationalcapital.gov.au/visiting/attractions/national_carillon.asp

Closer to the topic, Melbourne has a very unusual ‘war memorial’ in the Model Tudor Village (and it’s concrete) in the Fitzroy Gardens:

“Model Tudor Village – Tiny model buildings in cement and paint represent a typical Kentish village during the Tudor period in England. The village was opened by Lord Mayor Cr Raymond Connelly on 21 May 1948. The model maker was Edgar Wilson, a 77-year-old who built three such villages. The village was a gift to the people of Melbourne, sent in appreciation of the food parcels received by the people of Lambeth, London, during World War II.”

http://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/info.cfm?top=25&pa=1273&pg=1284

Although IIRC Loughborough has a good reputation for some of its engineering courses; quite what this says about engineer’s I’m not sure…

I had no idea about the origins of the model village, JDK! An article in The Age suggests that the models are probably made from bits of material scavenged from London bombsites, so it’s like a little bit of the Blitz here in Melbourne. (For non-Melburnians, there are some photos on Flickr.)

Ditto – I lived for years in East Melbourne and walked through the Fitzroy gardens to and from work. Since then (now living in NZ) I take my children to visit the village (and the fairy tree, and Cook’s cottage) when we’re visiting Melbourne. What a wonderful “extra” piece of context.

Pingback: Airminded · Not all of me shall die

Pingback: Airminded · Perth

Pingback: The Staff of Ra / Shrine of Remembrance | AlunSalt

Pingback: The one day of the century | Airminded