Previously, I identified a comparison between the reprisals debate in the First World War and the reprisals debate during the Blitz as something I could do that previous writers have not (except in passing, or implicitly). I won’t have time in my AAEH paper for a full-blown comparative approach, or for that matter time before then to do the research; though perhaps I could for a version for publication. But it’s something I can do briefly, and it helps that I already covered this in my thesis, where I looked at the British press reactions to the Gotha summer in 1917.1

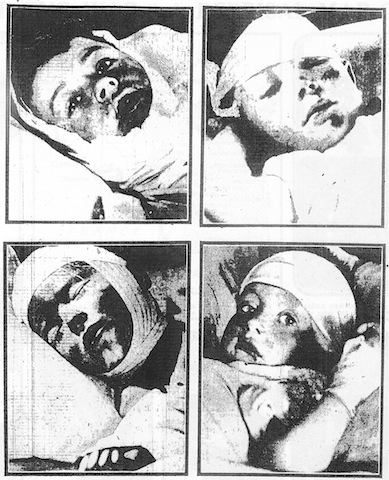

Schrecklichkeit is the German word for ‘frightfulness’; both words were used by English-language speakers during the war to refer to the perceived German propensity for barbarous acts of war. In terms of British public opinion, the ‘Rape of Belgium‘ was easily the most influential and inflammatory of these early in the war; later came the introduction of gas warfare; the execution of Edith Cavell; unrestricted submarine warfare; and of course the Zeppelin and Gotha raids on Allied cities, including London. Propaganda, mostly unofficial, kept this baleful view of the ‘Hun’ in the public eye. The photographs above, for example, were published in the Daily Mail after the first Gotha raid. The accompanying caption reads:

Four of the little sufferers in an East End hospital yesterday. Three are only five years of age; the fourth is ten. All were badly injured in the head, arms and legs while in a London County Council school in a densely populated district. All that was left of their classroom was a mass of blood-spattered debris.2

(These are victims of the tragic bombing of the Poplar infants school.) Another example is a letter published in an Australian newspaper, but relaying information from the London Chemist and Druggist:

The “Chemist and Druggist” of London, of February 23 [1918], informs us that the German blackguards had, during that month, been dropping poisoned sweets from aeroplanes in the London area. It is quite inconceivable that any British general would issue a similar order for the poisoning of little German children, or, if it were given, of any British airman obeying it. An occurrence like this brings home to one, more than many of their acts, what a degraded being a German can be.3

This sounds more like an urban legend than an actual tactic (and indeed, the only reference I can find to anything like this in The Times at this time is a rumour that strangers were giving children poisoned sweets in Kent), but it illustrates the depths to which it was believed Germans had sunk, and the essential difference between them and ‘civilised’ peoples like the British.

Though it was not the only response, the demand for reprisals in June and July 1917 was quite loud, and it did not just come from the press. Large public meetings held at Tower Hill and at the London Opera House endorsed resolutions such as one calling on ‘the Government to ‘pay back the enemy in the same way as he has treated this country’.4 Others went further. William Joynson-Hicks, a Conservative London MP, told the House of Commons that it was clear that Germany ‘has declared deliberate war on the nation, the men, women and children of our country’:

I submit to the House and the Government that the time is very rapidly approaching when, whether we like it or not, we shall be forced to declare war in the same way on the German people. Not that I have any desire whatever for the exercise of cruelty, or to slay Germans because they have slain our people. I say this because I believe it is the only possible way of bringing home to the German nation the enormity of what they have done — that is, the adoption of the policy on their part of destroying the English civilian population in the way they have done. I ask the Government to state, not that there will be a small and insufficient raid on a town like Cologne or any similar German town, but that as soon as a raid of this sort, involving, as it has done, 500 casualties, takes place, stern and swift reprisals will take place on German towns.5

Joyson-Hicks was not alone. Robert Bell MD, for example, wrote to the Daily Mail to insist that the Germans be told ‘that for every air raid they make upon an innocent community we shall do our best to destroy one of their cities’.6 The Mail helpfully published this ‘reprisal map of Germany’, placed on the same page as the above photographs of child victims of the Gotha raid:

A REPRISAL MAP. — The shaded parts of this map show those parts of Germany within reach of Allied aeroplanes similar to those used against London. All the large towns shown could be attacked.7

We can classify opinions in the debate about reprisals for German frightfulness along two axes: morality and effectiveness. People — at least those writing letters and leading articles — asked (and then answered) two questions: are reprisals moral? and are reprisals effective? Actually, that’s not quite true: they usually considered one or the other of these alone; the answer to the other was simply assumed to support their conclusion. Perhaps surprisingly, my impression is that those with moral concerns tended to be in favour of reprisal bombing, while those worried about effectiveness were more evenly split. Let’s look at some examples.

Joynson-Hicks, in his speech quoted above, went on to explain that

the only certain way of stopping these raids, in spite of the defence we may make by means of our aeroplanes and anti-aircraft guns, is that we shall punish, and punish severely, raids of this kind by inflicting similar raids with certainty — because they are useless without certainty — on German towns.

So his was an argument based on effectiveness: by bombing German cities you will make them stop bombing ours. (Deterrence, in other words. Others put forward versions of the knock-out blow theory, believing that heavy air raids into Germany would make its people clamour for peace.) Some, however, did not accept this logic. ‘Watchman’, in a letter to The Times, argued that

The best reprisal is the heaviest military blow. I can conceive of nothing weaker or more contemptible than to send our airmen off on long and hazardous expeditions without any military object, either direct or indirect, but merely to kill a certain number of children, women, and old men in the vain hope that the Germans will then cease from murdering our own civilian population […] Say we succeeded in killing two or three hundred civilians in Cologne, and lost, as we very well might, 25 aeroplanes out of 50 in achieving this result, how the Prussian High Command would chuckle and slap their thighs at having succeeded in inducing “these English madmen” to play the German game!8

In essence such arguments boiled down to the belief that these bombers and their pilots would be better employed on the Western Front, supporting the Allied armies there. (This of course is a major difference with the situation in the Second World War, at least after Dunkirk, where one argument for strategic bombing was that there was no other way to strike at Germany.) But note the bleedthrough of moralising language here: British airmen would ‘kill’ German civilians to stop German airmen from ‘murdering’ British civilians. And the cunning ‘Prussian High Command’, laughing as the foolish Britishers fall into the trap of tit-for-tat reprisals to no military purpose.

The moral arguments against reprisal bombing was straightforward enough: if it was wrong for Germany to bomb civilians then it was wrong for Britain to do so too. One bereaved mother expressed this as follows:

I have given two sons to the war (my only two) and they will never come back to me. I gave them willingly, and I have no regrets; I gave them to help to free the world from tyranny and barbaric savagery, and I believe that by giving up their young lives they have “done their bit” towards that end. But should I live to see Englishmen sent to murder in cold blood German women and children and harmless civilians, then indeed I should begin to ask, “Have my sons died in vain?”9

Another correspondent had no such qualms:

After the recent experience of German frightfulness, what other course is open to us but that of fighting the enemy with his own weapons? When the Germans used liquid fire against our brave fellows, were we not justified in resorting to the same method in order to protect our men from the most horrible of deaths, and to “bring home” to “the apostles of culture” the barbarity of their methods? […] To advocate the policy of “turning the other cheek” under present conditions, seems to me a misuse of Our Lord’s teaching. If a man hit me once, I should probably turn the other cheek and let him hit me again; and if that method failed to make him ashamed of himself, I should be compelled to “go for” him in self-defence. But if a man attacked my children, I should knock the brute down without the slightest hesitation.10

The author of this letter was J. Stephens Roose, president of the Metropolitan Free Church Association.

I could go on, but won’t. Hmm… maybe this is not something I can do briefly after all.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- The best published source for this is Barry D. Powers, Strategy Without Slide-rule: British Air Strategy 1914-1939 (London: Croom Helm, 1976), 81ff. [↩]

- Daily Mail, 15 June 1917, 6. [↩]

- Sydney Morning Herald, 20 April 1918, 11. [↩]

- The Times, 15 June 1917, 3. [↩]

- HC Deb, 14 June 1917, vol. 94, col. 1285. [↩]

- Daily Mail, 15 June 1917, 2. [↩]

- Ibid., 6. [↩]

- The Times, 9 July 1917, 6. [↩]

- Ibid., 18 June 1917, 10. [↩]

- Ibid., 19 June 1917, 7. [↩]

Pingback: Airminded · History never repeats

I always find it interesting to contrast the generally more obvious moral angst of the Great War with the somewhat more pragmatic view taken by most folks during the last war. They were perhaps more genteel, idealistic times, certainly there was a greater adherence to religion. Most of the allied combatants were also volunteers. What I think was very unsettling was that forces away on campaign could no longer presume that their kin would be safe from sudden demise at the hands of the enemy as they were before the advent of air power. This actually happened in the case of my own grandparents. The widespread use of gas during the Great War, by both sides, contrasts with the total absence of it’s use, as far as I’m aware, during the last war. The term ‘Hun’ was never used by any of my family of that generation and the Germans were normally referred to with respect. My grandfather had seen a great deal of death of friends as well as enemies. Perhaps it a truism, that those at home who had not been at the sharp-end, were far more likely to espouse jingoism and calls for revenge.

.

The ‘Poisoned-Sweets’ incidents has a parallel during the last war, when there was a widespread story of the Germans dropping booby-trapped pens in the UK. I can’t find any obvious reference to it on the web, but the story was certainly widespread, rather as the Italians had their ‘Pippo’, which was also reputed to drop exploding pens as well…! Interesting to see that the Italians had ‘mystery aeroplanes’ too….!

.

http://www.jstor.org/action/showArticleImage?image=images%2Fpages%2Fdtc.7.tif.gif&doi=10.2307%2F3814836

.

In terms of actions likely to provoke a public call for revenge in the last unpleasantness, the rather personal targeting of civilians might be thought to fit the bill. During the last war, allied bombers were generally to high to use their defensive guns against ground targets and it was often dark anyway. This contrasts with the Germans who, one often hears, used their machine guns in daylight against the civilians on the ground. I was always rather sceptical about this practice being widespread (The deliberate strafing of civilians.), but I have heard a lot of stories of such practices over the years on both the eastern and western fronts such as the staffing of refugee columns in France early in the war leading up to Dunkirk to slow-down the Allies. (This at a time when the SS were also known to have killed British prisoners without provocation.) My own mother witnessed this in the U.K. in 1941 when a policeman was killed by bullets from a low flying a/c yards from her house and it was certainly documented during low-level raids against factories. As I’ve mentioned before, the result was generally still ambivalence and acceptance of such thing as being part of the war, rather than creating any general upsurge in feelings. There was certainly a desire at times for revenge which lead to direct reprisals being exacted upon downed aircrew. It happened to allied crews later in the war in Germany, and there were specific examples of such revenge killings by British civilians as early as summer 1940 where several Luftwaffe pilots were bludgeoned to death. (I think ‘Eagle Day’ Richard Collier, mentions this, but I haven’t read it since 1969!)

.

In contrast, the freedom given, certainly later in the last war, to German prisoners is interesting. Many roamed freely, made friends and stayed in touch even after they had returned to Germany. Many also stayed and married. Well before the end of the war, my father was in Cairo, sitting in cafes with their recent foe and their was a total lack of ill-will. There was a surprising amount of good will in evidence.

.

The most obvious conclusion to draw, is that, certainly in the last war, anyone hoping to stir-up strong feeling for revenge was going to have their work cut out, with the Great War and the Depression to recent in peoples memory.

Fascinating about Pippo! I hadn’t heard of that one before. And I’ll have to look for the poisoned pen story (but cf. the next post).

On machine-gunning civilians from the air, yes, I believe that Luftwaffe airmen did do that over Britain, though I have to admit I was surprised when I started coming across these claims in the contemporary press: I don’t remember reading about it in the various Battle of Britain books I’ve read over the years. And you’re right about the high-level Allied bombers. But I think things were different in the last months of the war, when RAF and USAAF fighter-bombers were given carte-blanche to roam Germany shooting up anything that moved. I talked about this subject a little in a recent post.

The RAF and Commonwealth forces bombing at night used to have the occasional squirt at AA defences, but they were ‘fair game’. After the BoB, and until the German bombing offensive ran out of steam, attacks in daylight seemed to have often utilised cloud-cover to mitigate the normal lack of fighter-escort, which led to an emergence from the cloud near the target at medium to low-level before exiting the same way. I’ve come across several accounts of aircraft factories etc being attacked this way (Vickers Armstrongs, at Castle Bromwich, Birmingham for example.). These seem to have been when the machine-gunning took place. Later, on the eastern front, such things may have been more commonplace, but they stand-out more in the context of the war over the UK which was generally a ‘cleaner’ affair. I’m not sure what it tells us about the attitude of the Luftwaffe, but any reaction in the UK was very muted. At the time of the machine gunning of the Police Officer mentioned in my previous post for example, there was a considerable outcry about the fact that much of the munitions dropped were actually supplied by Britain..! (When it was abandoned in France.) Interestingly, around this period, little mention is seen in the usual sources about fighter a/c venturing far afield (ie;- beyond the then range of the ‘109.), yet on occasions they did, as I’ve spoken to people who saw them, even at night, Me110’s of course. (or Bf110’s for the pedants out there, although this term wasn’t normally used during the war.).

Sorry, I hadn’t seen your post of 12th April. A bit of duplication here.

Pingback: Airminded · Precisely

Pingback: Airminded · Putting it together

Pingback: Airminded · Black death rain

Pingback: Eleven, Eleven, Eleven — II – Airminded