Stanley Baldwin’s ‘the bomber will always get through’ speech was not widely quoted in the British press in the 1930s. But when it was quoted, how was it used? To determine this, I’m going to do a closer read through of the British Newspaper Archive (BNA).

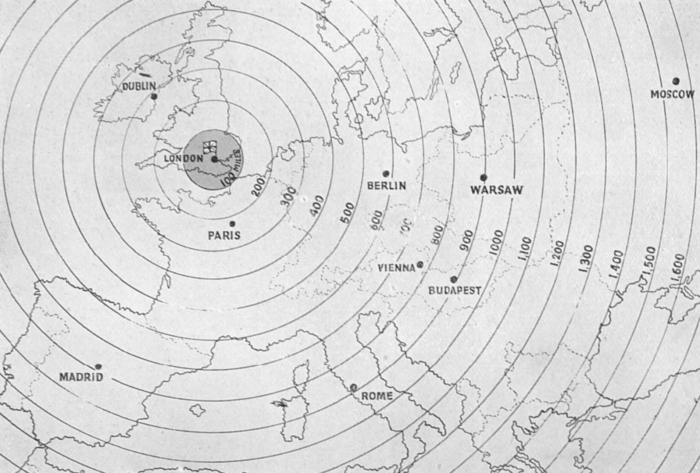

The first uses, of course, were in late 1932 in reports of Baldwin’s speech. Only a handful of quoted ‘the bomber will always get through’, mostly neutrally. The Illustrated London News, however, juxtaposed the speech with photographs of anti-gas schools and air raid exercises on the Continent, or from the ‘Air Exercises over London’ (above).1 The Central Somerset Gazette prominently featured the phrase in an article by Hilda Clark, a medical doctor and a pacifist, under the subheading ‘Plain truths from Mr Baldwin’.2 In both of these cases, Baldwin’s claim was presented as being true or at least believable.

There weren’t many appearances of ‘the bomber will always get through’ in 1933, but they are again all supportive. It was invoked in debates about dismarmament carried out via letters to the editor. For example, E. G. Rymer used it to buttress their claim that ‘it has been made abundantly clear that there is no protection against an air attack […] The whole thing seems so plain to my thinking’.3 It was also used in some signed articles, again positively. Storm Jameson said of Baldwin’s ‘warning’ that it ‘is so precise that it should be in all our mouths’.4

1934 is the first big burst of interest in ‘the bomber will always get through’ in BNA, with more than five times as many appearances than in 1933, just over half of them in the last third of July. What was happening then? A parliamentary debate on the proposed expansion of the RAF in response to Germany’s imminent aerial rearmament. It was Baldwin — still only Lord President of the Council, but the real power in the National Government — who introduced the bill, and unsurprisingly found his words from 1932 used against him by Lord Ponsonby, Labour’s leader in the Lords:

Lord PONSONBY quoted the recent statement of Mr Baldwin — ‘We want the man in the street to know that there is no power on earth that can protect him from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through.’5

He claimed that Lord Londonderry, the Secretary of State for Air, ‘had never denied the truth of that statement, and that the Under Secretary for Air had confirmed it’.6 His point was that

If any Government could guarantee the safety of this nation by spending vast sums on a huge Air Force this matter would be different. But, as we know, this Air Force is no defence. It is not going to be used for attack, and defence by retaliation is an argument that won’t hold water. The mere desire for parity really is an idle an insufficient reason for alarming this country with a declaration of this new policy.6

Baldwin defended himself in the Commons a week later:

Mr Baldwin then turned to his much-quoted phrase — ‘The bomber will always get through.’ and denied that it was any argument against a stronger Air Force. Some bombers, he repeated, would always get through, but, if they had a strong force, there would come a point when the attacker, realising the difficulty of his task, would begin to seriously consider whether the game was worth the candle.7

Clement Attlee, Labour’s deputy leader, responded by saying that the Government only paid ‘lip service to the League of Nations, and to collective security’, in the end retaining ‘the belief in the eventual reliance on the old principle of self-defence’; but

Mr Baldwin had told the House that day not to deceive the man in the street, and the Opposition would continue to say [what] Mr Baldwin said in November, 1932, and that was ‘The bomber will always get through.’8

So, again nobody is disagreeing with Baldwin’s claim that ‘the bomber will always get through’, including Baldwin himself (!); it is seen to represent received wisdom. Instead, they differ over its interpretation. For Baldwin it proves the need for parity in aerial armaments; for Labour it proves their futility.

It’s interesting that the The Scotsman described ‘the bomber will always get through’ as Baldwin’s ‘much-quoted phrase’. And a leading article about the debate in the Dundee Courier and Advertiser used it divorced from Baldwin, to stand in for the knock-out blow theory itself:

The objection that no real defence against raiding aircraft is possible — ‘the bomber will always get through’ — is no justification for continuing our present state of conspicuous inferiority in the air.

There is no escape from the conclusion that the ultimate basis of air defence is to have a force of fighting planes sufficiently strong to retaliate on a scale that would make it unprofitable for an enemy to open the attack.9

That is pretty much I how expected ‘the bomber will always get through’ to be used before I started digging into this question. Maybe there’s hope for it after all? I’ll look at 1935 and beyond another time.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Illustrated London News, 19 November 1932, 4, 5. [↩]

- Central Somerset Gazette (Glastonbury), 18 November 1932, 2. [↩]

- Daily Mail (Hull), 28 November 1933, 13. [↩]

- Daily Herald, 18 July 1933, 8. [↩]

- Scotsman (Edinburgh), 24 July 1934, 10. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., 31 July 1934, 9. This was the occasion, incidentally, for Baldwin’s other famous piece of phrasemaking on the aerial threat: ‘Since the day of the air the old frontiers are gone. When you think of the defence of England you no longer think of the chalk cliffs of Dover. You think of the Rhine. That’s where to-day our frontier lies’. Ibid. I probably should write something about this one day. [↩]

- Belfast News-Letter, 31 July 1934, 7. [↩]

- Dundee Courier and Advertiser, 24 July 1934, 6. [↩]