The Royal Navy is about to pay a high price for its neglect of airpower …

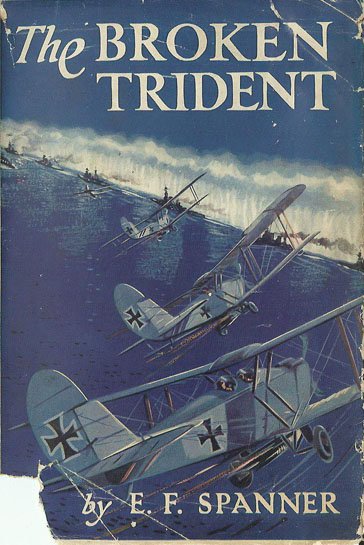

Front cover of E. F. Spanner, The Broken Trident (London: E. F. Spanner, 1929).

I just like this picture for some reason. Spanner was a retired naval architect who evidently had at least one bee in his bonnet, for he wrote about half a dozen books on various aviation matters (including the inadvisability of the government’s Imperial airship scheme — well, he was right about that), and what’s more, he published them all himself! The Broken Trident was originally published in 1926, and the cover above is from the 1929 “cheap edition” (price: 2/6), so either the first edition sold enough to warrant going down market, or probably more likely, he wanted to get his message out to a wider audience. There was also a German edition (1927), which I’m sure would have sold relatively well, given the effortless ease with which, in the novel, a supposedly downtrodden Germany bests a smug and complacent Britain.

Update: I was looking at another book of Spanner’s today, Armaments and the Non-combatant: To the ‘Front-line’ Troops of the Future (London: Williams and Norgate, 1927), which is a non-fictional rendition of many of the ideas in The Broken Trident. So obviously not all of his books were self-published (as I stated above), at least the first editions, contrary to what the cover of The Broken Trident suggests. In Armaments and the Non-combatant, Spanner notes (p. 295) that he wrote The Broken Trident (among other books) as a novel because ‘in that form I thought it easy to present facts and probabilities so that they might gain the attention of technical men of all shades of thought and also the attention of ”the man in the street”’, and appends excerpts from its favourable reviews. The title page also notes that he’s the ‘Inventor of the Duct Keel system of Ship Construction, the “Soft-ended Ship” system of Bow Construction, the “Spanner” Strain Indicator, etc’.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Unexpected flashes of humour No.1: Group Captain Harris to Captain Tom Philips, JPC July 1936 – ‘When you are on the bridge of your flagship and you are struck by a bomb, you will say to your captain that was a bloody big mine we struck.’ (Gaines Post, Dilemmas of Appeasement: British Deterrence and Defence 1934-1937, (Ithaca, Cornell UP, 1993), 322. Sure you’ve come across that one before, but just read it and thought that it was particularly relevant to your post!

I didn’t know that one, thanks! Sounds like “Bomber” and Spanner would have got on famously, though ultimately the latter’s loyalties still lay with the Admiralty. (Spanner had this idea that bombs could be made to strike and explode well below the waterline, where the hull was very thin, which would have been just like a mine or torpedo. Barnes Wallis’ dambusting bombs could be used for this, eg against the Tirpitz, but it was nowhere near as easy as Spanner assumed it would be …)

There’s an update (from Post’s footnote) which makes me wonder about the authenticity of this quote. Philips went down with the Prince of Wales in 1941. That just makes it all a bit too neat, doesn’t it?

Can’t help thinking that Spanner should have invented a nut adjusting device: the patented Spanner Spanner.

Even better, if a bunch of sado-maschochists in the north-west used one for some foul purpose in the late 1980s, and it was admitted as evidence in the subsequent controversial Old Bailey trial, we could have had the Operation Spanner Spanner Spanner. Who says that we live in the best of all possible worlds?

Philips was known as a big gun man in the 1930s, and when director of plans he was a Captain and thus of equal rank to Harris, who was in flying boats in the early 1930s. So the exchange is possible but, as Dan said, it still sounds rather too good to be true. Is it just another bit of ammo from the anti-historians?

Post’s footnote gives the source as ‘General Sir Ronald Adam, letter to the author, 30 June 1974’, and the context is the discussion over ‘ownership’ of the Fleet Air Arm/shore based aircraft in the JPC. Personally, I found Post’s book extremely useful and convincing in its interpretation (if not always brilliantly written). Not a salvo from the anti-historians, then, but perhaps a piece of evidence which was improved with memory? I’m happy to believe that Harris said it at some point, even if not to Philips, and it does seem to convey something of the emotional tone of the arguments at the time.

I grew up with much of this stuff but it is just the tip of the iceberg. My grandfather was far from being a retired naval architect as one of your commentators suggests, these books were just ‘pot boilers’ to help family finances. He held admiralty contracts on merit (he was not impressed by by their lordships) and fought his corner as an inventor and inovator vigorously. always having to prove himself the hard way. The broken trident shows his viewpoint from 1926. and he eventualy became an advisor on naval construction stuff to WSC himself-a man who had been drawn similar conclusions about Germany in those times. He predicted the R101 crash based on structural stress calculations and was unfortunately for the crew not many miles out. His pre flight prophecy and warning earned him immediate loss of Admiralty contracts and a front page headline in The Times. They had to print an apology and retraction of course (went against the grain) and he had his admiralty contracts restored. He always shunned the limelight preferring the world of naval engineering and architecture. The company he founded was taken over by Babcocks in latter years and I understand many of his (and his sons) patents are still valid. This is just a small snapshot of the man.

Thanks for your comment! Your account of your grandfather fits pretty well with the image I’d formed from reading The Broken Trident and Armaments and the Non-combatant — inventive, tenacious, blunt — though of course adding a number of details I was unaware of. But what you say also raises some further questions!

You say he was ‘far from being a retired naval architect’. Do you mean he wasn’t retired, wasn’t a naval architect, or that he was more than the sum of those descriptions? I don’t have a good account of his career, but he signed the preface of The Broken Trident ‘E. F. Spanner, M.I.N.A., Royal Corps of Naval Constructors. (Retired.)‘, where MINA is presumably ‘Member of the Institution of Naval Architects’.

You also say his books were ‘just ‘pot boilers’ to help family finances’. Do you mean that he didn’t mean them to be taken very seriously — that he had no strong opinions on the subject of airpower and was merely writing what he thought would sell? Or — and reading your comment again, this seems to be more likely — that these were indeed his opinions on the subject, but that he wouldn’t have published them if not out of financial necessity?

A follow-up to the previous question: did they in fact sell well? Do you have any idea as to how many copies were sold?

Again, thanks for taking the time to comment, and I appreciate any further information you can provide!

This is a fascinating prophesy of the next war with Germany as seen from 1926. The whole war lasts less than a week and ends with an almost benevolent Germany giving the Brits generous peace terms resulting in what may have been the beginning of a Euro union. The war is predicted to happen in 1930 or 1931. Well he got some things right but not the nature or duration of the war that began in 1939. That one with a Mad Dog Germany was to last 6 years. Still other predictions are dead nuts on, such as the destruction of the Battleships by torpedo strikes to the rudder, which took out both the Bismark and her antagonist Prince of Wales in 1941. Another dead nuts on prediction was the aircraft with variable pitch wings. Altogether a great work.

Nice to meet another Spanner reader, there can’t be too many of us around! Though I was reading it for research purposes, rather than enjoyment, assessed against other novels from the period on similar topics it was probably better than most. Almost a techno-thriller, given the many ideas for new weapons and tactics he throws at the plot, some of which are dead-on but most of which are more imaginative than realistic. The ‘variable pitch’ wing you mention, for example; I think this is actually a variable area wing, as it is described as ‘a wing with a variable area of lift’ which allows ‘a machine to combine the ability to climb with great rapidity with the power to cruise at high altitudes at relatively slow speeds’ (74). I don’t know of any aircraft actually built to this principle (though I could be wrong, and Pemberton-Billing’s slip-wing concept was another approach to solving the same problem). Another example is the incident on the front cover shown above: the British battleships are silhouetted against a smokescreen, illuminated by magnesium flares, laid by the German aircraft to make them good targets for a torpedo strike (207-11). Again, it’s a cute idea but was it ever used in practice? Not that any of that should stop you from enjoying the novel!

There’s a rich history of messing around with dynamic wing shapes, going a lot further back than most realise, as much of it was abortive due to the limits of contemporary power and or engineering.

However, among many others, Fairey’s had the patented variable camber wing as standard and effective from, IIRC, the 1920s (which was basically drooping flaps and ailerons, first used in 1917 on the Hamble Baby) while the Airspeed Fleet Shadower offered long, high, loiter time (as it’s now called) and would’ve had excellent slow-speed climb performance. As well as being a deathtrap in W.W.II combat.

Also the G.A.L.38.

The variable pitch wing was effective in the Supermarine Type 322 ‘Dumbo’ but not wanted, and there were much earlier efforts on that line, as well as a later personal favourite, the 1948 Supermarine Seagull ASR amphibian. Helicopters did for the ingenuity of the Griffon-powered Seagull, and Radar for the shadowers and the need for backlighting fleets – though that’s a rough summary of a much more complex naval-warfare subject.

Sounds like E.F.Spanner was on the ball for what could be foreseen, and of course we don’t know the unknown-unknowns in futurisms… Want to read it now.

battleships are silhouetted against a smokescreen, illuminated by magnesium flares, laid by the German aircraft to make them good targets for a torpedo strike

The RN certainly used flares during the Taranto attack, and were planning on using them (to assist MTBs) during the version of the Channel Dash that they were expecting ( http://www.channeldash.org/swordfish38.html ). I have a vague feeling that they were used during the successful Swordfish attacks on Italian shipping in the Med?

Found a ref to actual torpedo attack at sea assisted by flares.

http://maltagc70.wordpress.com/2012/09/05/30-august-5-september-1942-malta-faces-malnutrition/

JDK:

I can be numbered among those not aware of most of that history! But I don’t think Spanner was talking about variable pitch, variable camber, variable incidence or variable geometry, but simply variable area — another bit I didn’t quote is his description of ‘a wing having a variable area of lift, the increase or decrease of the wing surface being obtained by the pilot, by means of a simple controlling gear’ (74). Perhaps I am being over-literal.

Errol:

It’s not the use of flares to illuminate targets that I’m questioning. In fact, Spanner doesn’t suggest that at all; rather the flares are used to illuminate a smokescreen which in turn is used to silhouette the battleships (as in the picture above). From p. 208:

And from p. 209:

(And he was right!) Even if something like this was ever tried, it certainly never became a standard tactic. It’s clever but, like many predictions made in this genre, overly-complicated. Spanner gets away with it because he’s writing fiction, so every plan of the fiendishly clever enemy works like clockwork. Reality isn’t usually so predictable.

I guess from my perspective, having read quite a few knock-out blow novels, I tend to resist reading them for their predictive accuracy. For one thing, even on that level isolating what they got right ignores the many more things they got wrong. But also that it’s more interesting to ask why they made the predictions they did. In some respects Spanner was kicking against the basic knock-out blow paradigm, as he didn’t think that it would be worth bombing civilians directly; but he still subscribed to many of its tenets as shown by some of his other ideas: he advocated dropping AA guns entirely (aircraft are too fast now to be effectively targeted and shrapnel will do more damage to civilians) and has London attacked not by bombers but by aircraft circling above making noise (to keep people awake and make the defences waste resources). His position was something of a bridge between airpower prophets and navalist sceptics.

My kind of trivia time! Points taken, but just a gloss. Variable geometry wings usually change area (as well as lift factors) in one way or another (think your airliner wing’s slats and flaps which overlap when not deployed).

However, going to straight change of area, there were at least two designs in 1932: http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1932/1932%20-%200449.html

The telescoping wing goes back even further (i.e. I haven’t found the design I was thinking of – yet!) but arguably apart from 1970s glider designs has been more trouble (weight / complexity) than it was worth, but it *did* exist.

I agree the ‘fiendish plan’ in the Spanner book is classic Boy’s Own complexity (and sounds *thrilling*!) but backlighting or illuminating was a key factor in naval strike, and I’m sure the pioneers would tell us that smoke floats and magnesium lights would’ve been a sight easier to make work than pioneering ASV radar at times. The original ‘black boxes’ in some versions. My reading on early radar covered accounts of smoke and sparks, but inside the aircraft…

On a complete diversion on air-sea strike backlighting, there’s the real story of ‘Project Yehudi’, which worked, was effective, but not needed in the end. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yehudi_lights

However I agree with your overall view, Brett, I just like to find what-widegets-were-there!

I’d never heard of the Yehudi Lights – fascinating! Thanks for that, James.

I love those kinds of technological oddities, and that’s a particularly neat one, eh?

On the topic of future prediction, I found this ABC article posted the other day as pretty relevant to this discussion:

“The UK-based science fiction writer Charlie Stross takes a very practical approach to the task of predicting future change: ‘Attempting to extrapolate how the world will look exactly in say ten or twenty years is really rather difficult,’ he once told me in an interview. ‘However,’ he went on to say, ‘one rule of thumb that is applicable is that the future looks just like the present 95 per cent of the time—and then you add five per cent unutterable weirdness on top.’

So, one thing we are clear on from past experience is that 2023 will look pretty much like 2013—at least on the surface of it. But if we accept William Gibson’s idea that the future is a process linked to the present, rather than some sort of ongoing series of abrupt new beginnings, then it’s possible to make meaningful assumptions about what lies just ahead. With one caveat, of course, that it’s well nigh impossible to predict the arrival and impact of truly disruptive technologies: the development of the Internet being a prime example.”

http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/futuretense/where-will-we-be-in-2013/4697232

And that’s a pretty good summary of why E F Spanner was clearly sharp, and on the ball, but not right overall – it was those ‘disruptive technologies’.

And of course you can have a wizz-bang idea, which has some potential, but perceived need for secrecy means that you can’t make good use of it!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canal_Defence_Light

JDK:

Well, sure, he saw a problem that needed to be solved, but, after all, he was a naval architect and being aware of such problems was part of his job description (searchlights were used for target illumination during the Russo-Japanese War, for example). I shouldn’t fault him so much for getting the technology wrong: yes, he was trying to anticipate the next disruptive technology and most people, even most experts, fail at that. But really, what I’m pushing back against is the tendency to judge such predictions on the basis of their accuracy (which I anyway share myself, and objecting to a blog comment on this basis is admittedly rather pedantic). David Edgerton (a la The Shock of the Old) would probably agree with Stross that the near future is 95% now plus 5% weirdness, but then would ask why do we focus so much on that bleeding edge 5% instead of the boring old 95%? This is common in technological journalism, technological fiction, technological history — and works such as Spanner’s. The answer in his case is because he was a polemicist trying to change things in the present, so he made up a story about the future to ‘prove’ his point. Kind of like Sandbrook and the past, in a way… Anyway, I think I’m starting to repeat myself so I’ll stop!