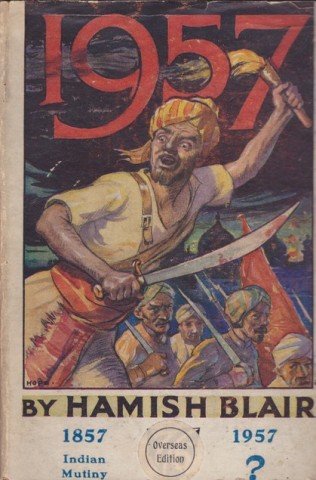

I may be the only person now living to have read all three of Hamish Blair’s novels, published in 1930 and 1931 — I’m certainly the only person on LibraryThing to own any at all.1 I wish I could say that the rest of you are missing out, but you’re really not: they are tedious as fiction and barely more interesting as future war fiction, which is the reason I bought them. Read consecutively, however, I can at least say that his writing did improve somewhat over the three books. And his first novel, 1957 (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1930), is a rare example of future colonial war fiction, and an even rarer example of future colonial air war fiction. So it’s worth looking at for that reason alone.

Hamish Blair was the pseudonym of Andrew James Frazer Blair, a journalist born in Scotland but who seems to have spent his working life in British India, presumably in Calcutta, the setting of his first two novels. His novels all involve India in some way. The protagonist of the third, The Great Gesture (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1931) is on leave from the Indian Civil Service, though the novel is set in Europe (about a confrontation between the United States of Europe and the United States of America, with Britain siding with the latter). Both 1957 and its sequel, Governor Hardy (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1931), are squarely focused on India. Only 1957 features airpower in any significant way.

As its dustjacket rather broadly hints, 1957 is about a second Indian Mutiny, exactly a century after the first. Blair is unashamedly pro-British; he barely attempts to justify the British presence in India. There is a suggestion that if the British left, the country would fall into sectarian chaos, but it’s only made in passing. Blair’s warning here, of course, is that it might very well fall into chaos even if they stayed, because they are not prepared to rule with as iron a fist as he believes is required. A coalition of disaffected Indian princes secretly plot an insurrection while the leaders of British India supinely look on — the Viceroy is forced by the Labour government at home to order a loyal prince, the Sultan of Jehanabad, to allow a Communist demagogue to spread sedition in his state. The uprising eliminates most British military forces on the sub-continent as well as the civil government at Delhi (which city Blair clearly detested). Only pre-emptive action by the maharaja and the leader of a Calcutta militia, John Hardy, preserves any chance for British victory when the uprising begins by forcing the rebels to make their move early; Hardy carries out a coup in Calcutta which is retrospectively endorsed by the new government at home, after a popular outcry forces Labour out. With Calcutta secured, Hardy’s forces and those of the loyal princes converge on Delhi to engage the occupying forces. They are outnumbered but their resistance upsets the rebels’ plans, as does the failure of neighbouring Bokharistan to intervene as promised, and they start to fall out among themselves. Reinforcements from the Empire are arriving by now and deliver the coup de grace. The Sultan is killed in the final battle, but Hardy survives and his rewarded with a baronetcy and the governorship of Calcutta and also wins the hand of the Sultan’s ravishing sister in marriage. So everything ends happily ever after, except for all the civilians, British and Indian, killed in the fighting, though only the former are paid any attention at all. And except for the things that happen in Governor Hardy.

Aviation in the world of 1957 is only slightly more advanced than in that of 1930. There’s little evidence of any technological advancements, apart perhaps from a ‘Fox superplane’ with a range of 3500 miles and ‘a suite of luxurious apartments in miniature’.2 Air travel does seem to be more common, as it’s not uncommon to fly to India; but it’s still usual to go by ship. There are more aircraft around. Britain has enough to airlift 12,000 soldiers in to Karachi from the Middle East; and Bokharistan, an obvious stand-in for Afghanistan, has 500 aircraft. There are actually two air forces in India: the Royal Air Force and the Royal Indian Air Force, the latter (which wouldn’t exist until two years after Blair wrote, and not under that name for another fifteen) the result of a policy of ‘Indianisation’. Their airfields and organisation are segregated, though the RAF relies on Indians for its groundcrew. This arrangement proves to be a fatal weakness, as the sepoys sabotage the RAF’s aircraft before the RIAF squadrons bomb and strafe their British neighbours in one of the novel’s most striking images:

At daybreak, Captain Michael Macready, Station Staff Officer of Delhi, was awakened by terrific detonations. His bungalow was situated midway between the British and Indian lines, and about a mile from the British aerodrome. He went out on to his verandah, and looked towards the north. He heard more detonations, he heard the drone of aero engines. Looking up, he saw a dozen Indian machines in the air, apparently dropping incendiary bombs on the British aerodrome. These were followed by further explosions, sheets of flame, and columns of smoke.3

This surprise attack, which is repeated across India, is decisive; the RAF is effectively wiped out and the only aircraft available to the British are those of the Calcutta militia and the loyal princes, and these are heavily outnumbered. But this seems to be without consequence. Blair tells us more than once that airpower is the decisive factor in warfare (the RAF being described as ‘the most important of all’ British forces in India, for instance), but he doesn’t actually show us until very late in the novel.4 For example, the Allies learn that ‘the air strength of the rebels was out of all proportion to their own’, due to the success of the air strikes on the first day of the mutiny:

It left the mutineers with a preponderance of 300 to 400 planes, including bombers and fighting machines, while the Allies mustered less than 150, of these most were required for patrol and escort duty on the long line of communications. Moreover the rebel fliers were regular airmen who had developed a high level of proficiency, and were both plucky and keen.5

This realisation is underscored by a rebel strafing attack on an Allied column, causing a panic among the Sultan’s men. He goes up himself (!) to help drive off the enemy, and is wounded in the process. The few Allied machines are ‘overwhelmed and practically destroyed during the first week of the fighting before Delhi’.6 This superiority in the air does force the Allies to move at night, but doesn’t stop them from advancing. It could be argued that this is a realistic view of the limitations of airpower. But then Blair also notes the dependence of the Allies on air supply. How did the rebels neglect to use this advantage to strangle the Allies logistically?

The Allies dig in before Delhi and withstand wave after wave of rebel assaults (this is the extent of the Anglo-Indian strategy). Again the rebel advantage in the air makes no difference. The arrival of British reinforcements — interestingly, under the overall command of an air marshal, ‘Sir Bryan Nevile, the most formidable air leader in Europe’, even though the Army makes up their bulk — overthrows the balance in the air: ‘The sky was dark with their wings, and the air vibrant with their engines’.7

The attacking air force now proceeded to exact toll of the rebel city; and at the same time the small allied army holding the line between Tughlakabad and the Kutb, reinforced by infantry and artillery motored up from Bombay, began to throw a cordon round it. Delhi was battered by high explosives from the British entrenchments as well as by gas-bombs and other projectiles from the air.

The city was well provided with underground shelters. These had been deepened and increased during the three or four weeks which had elapsed since the mutiny began; but three days of such an inferno as now descended upon it were too much for the rebel moral. Deserters began to quit the old city, and a stream of refugees poured out by night as well as by day.

Rockets and shells lit up the whole area by night, and British patrols spotted the fugitives from the air. Although encirclement of the vast perimeter was not complete, detachments were thrown across all the routes of egress, and prisoners were swept up by the thousand.8

This is pretty much a knock-out blow (though note that it’s not delivered by airpower alone). It forces a change in the rebel leadership and a resolution to negotiate a peace. The end of the war does come via the air, but not through the action of the RAF: the deposed rebel leader takes his revenge by dropping a bomb from his Fox superplane on his former comrades’ fortress, accidentally detonating an ammunition dump next to the Jumma Musjid mosque, destroying it. This own goal finally takes the fight out of the rebels.

There’s more that could be said about Blair’s attitude to Indians (using gas on civilians seems to be okay), women, Labour, Communism, democracy, dictatorship, Jews and so on, in 1957 as well as Governor Hardy and The Great Gesture — though the mere fact that he wrote enough articles for the right-wing Saturday Review to be able to publish a collection of them will probably give a sufficient indication of his reactionary politics.9 The less said about the dreary and trite romantic subplots the better.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- The author of the Science Fiction Encyclopedia entry about Blair perhaps excepted, though the (admittedly brief) plot descriptions are misleading in two cases. [↩]

- Hamish Blair, 1957 (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1930), 317. [↩]

- Ibid., 220. [↩]

- Ibid., 204. [↩]

- Ibid., 289. [↩]

- Ibid., 295. [↩]

- Ibid., 313. [↩]

- Ibid., 313-4. [↩]

- From the title (India: The Eleventh Hour) and the date (1934) evidently a diehard attack on the India Bill. I haven’t read this, but maybe I should, just for the sake of completeness… [↩]

You’re not going to cause a run on secondhand copies with your opening remarks, there Brett! Interesting post though.

By the way ‘Hamish Blair’ isn’t probably a pseudonym in the way people often think of them as a disguise (obviously, for the unchanged surname) as ‘Hamish’ is actually equivalent to ‘James’. For instance publisher Hamish Hamilton was actually James Hamilton, but clearly used both names. It’s possible that Hamish Blair may simply be the name he was more widely known to friends or any audience as.

Yes, that makes sense. It’s one thing for a journalist to publish novels under another name; but it would then be a bit odd for him to publish a collection of non-fiction pieces (on a subject he clearly felt strongly about) under the same name. So it was probably his working name.

I read your comments on these books with interest and amusement because Hamish Blair was my father-in-law’s grandfather. It seems that he used ‘Hamish’ for writing (at least). This is an obituary for him that I found on the Times Digital Archive: “Mr Andrew James Fraser Blair, whose death at the age of 62, at Wellington, in the Nilgiri Hills, is announced by Reuter, was one of the oldest British literary men resident in India, where he made a distinct mark in authorship and journalism. He was born on September 30th, 1872, at Dingwall, Ross-shire, where his father, Andrew Blair, was rector of the Burgh School. After education at Glasgow High School, he began his journalistic career in 1890 as a sub-editor on the Birmingham Daily Argus. In 1895 he joined the staff of the Calcutta Englishman as assistant editor, and held charge as editor from 1898 to 1906. He then became editor and managing director of two enterprising papers, Empire Commerce and the Empire Gazette. In 1912 he founded the Eastern Bureau, Limited. He had a quick and vigorous pen, and contributed short stories and articles to the Press in India under the nom de guerre of Hamish Blair. Later he joined the staff of the Statesman, went on the board of directors, and for some years served as assistant joint editor. On retiring in 1930, he was disinclined to end his days in his native land and settled in Ootacamund. His novels included “1957”, “Governor Hardy” and “The Great Gesture”. He married in 1900 Constance, elder daughter of Thomas Ibbotson, a lady who shared his literary tastes. She survives with a son and daughter.” If you still have the books and want to offload them for a modest sum (it doesn’t sound like you will be reading them again!) then please do email me.

Nine years later and I’m still the only owner of any of Blair’s books in LibraryThing!

Tony, thanks for the biographical info about your father-in-law’s grandfather — explains his interest in India, certainly. I think I’d be happy to offload the books, if you’re still interested; I’ll drop you a line.