Looking over the list of Australian mystery aircraft sightings suggests that some generalisations can be made.

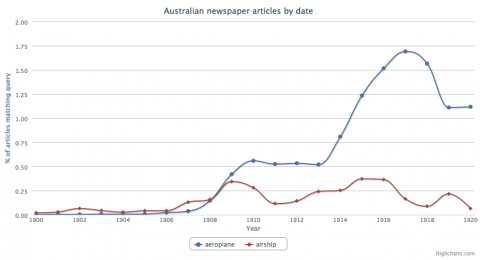

In the 1910s, mysterious lights in the sky were usually described as being airship-like; after 1910 they were far more likely to be called aeroplanes. Perhaps not coincidentally, 1910 was when aeroplanes first flew in Australia; certainly a search of Trove Newspapers (using Wraggelabs’ QueryPic) shows that 1910 was the first year when the word “aeroplane” appeared markedly more frequently than “airship”. So that’s easy enough to explain.

The same search shows that 1909 was the year that aviation really broke through into public consciousness. That’s also the year of the Australian phantom airship wave.1 As it was the first burst of interest in aircraft, the first time that people started to learn about them, it’s perhaps not surprising that people might think they saw them flying around where they weren’t. The 1918 mystery aeroplane scare came after several years of increasing press coverage of aviation, obviously due to the war. So again that fits. Aeroplanes were something people were reading (and probably talking) about a lot. But that by itself is evidently not enough to generate a mystery aeroplane scare: there were a few seen in 1914, and a handful in the years after that, but nothing on the scale of 1918. There needs to be a plausible reason for aircraft to be flying about: and the reported visit of the Wolf and its Wölfchen to Australian shores provided that, though the desperate situation of the Allied armies in France was also a factor.

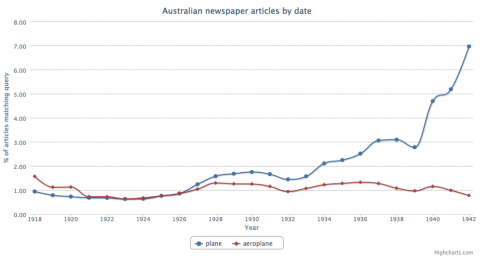

After 1918 there is a lull; I couldn’t find any mystery aircraft sightings until 1927, when a few start to pop up. (Which certainly doesn’t mean they aren’t there to be found. I just found another one, albeit for 1928 as well.) Why might that be? Well, looking at the ngram above again is suggestive. This time the plot extends covers 1918 to 1942, and is for ‘plane’ as well as ‘aeroplane’ — the former becomes more common from the late 1920s.2 After a relatively flat level of interest in aviation during most of the 1920s (actually falling considerably from the immediate postwar years), the number of articles using the word ‘plane’ almost doubles between 1926 and 1928, after which it is fairly stable until a dip in 1932 and 1933. So once more there’s a buzz about aeroplanes (or rather planes), a widespread curiosity about aviation. Why was this so?

It was certainly nothing to do with fear of war in these Locarno years. I haven’t tested this quantitatively, but it can’t be a coincidence that these were the years of some of the great pioneering long-distance flights. Australia was the destination and, in some cases, the birthplace of many of the aviators who carried out these feats: the Englishman Alan Cobham flew from England to Australia and back in 1926, for which he was knighted; in 1928, Bert Hinkler, an Australian, was the first to make the trip solo. That same year, Charles Kingsford-Smith and Charles Ulm, also Australians, were the first to fly across the vast Pacific and then the smaller Tasman. The excitement that Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 New York-Paris flight generated is well-known; something similar happened, if perhaps less intense, must have happened in Australia.3 The emotional investment in these pioneer aviators and their dangerous lives perhaps explains the number of false reports of aeroplane crashes around 1930.4

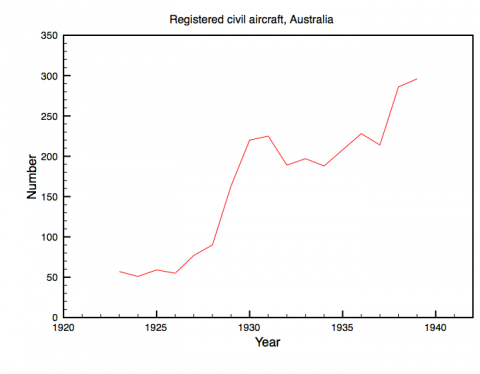

And it wasn’t just the big names either. Here’s a plot of the number of civil aircraft registered in Australia from 1922 to 1939.5 Between 1926 and 1928, this increased from 55 to 90 or 63% (and then another 144% between 1928 and 1930).

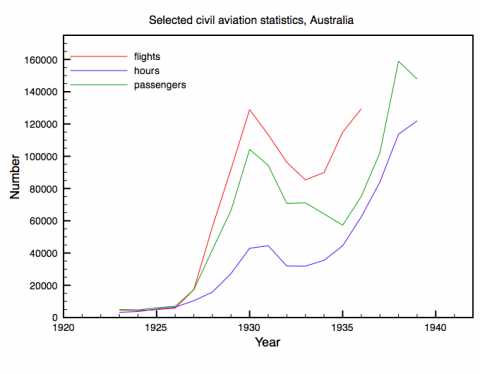

Other statistics — number of flights, number of hours flown, number of passengers carried — tell the same story.6 There was a huge increase in flying in the late 1920s, followed by a bust (no doubt due to the Depression) and another boom in the late 1930s. So it makes sense that mystery aeroplanes began to be seen again from 1927-8 or so. It was the golden age of Australian aviation: far more people were talking about and flying in aeroplanes than ever before.

Apart from the air crash theory, other explanations for mystery aircraft in the late 1920s and early 1930s included opium smugglers and — in 1934 — a Japanese reconnaissance of the northern coast. Japan was invoked, either explicitly or implicitly, in the Darwin and Hobart sightings in 1938, and the Townsville incidents in 1942. This brings me back to my original purpose in starting this series, which was to see if Australian mystery aircraft sightings can be used as an index of public anxiety about national defence. And my answer is ‘yes’, but it’s a heavily qualified ‘yes’. It’s quite obviously so in 1918 and 1942, but then the country was at war (and in the latter case actually under attack), so that’s no surprise. In the late 1920s and early 1930s there was no cause for Australians to be alarmed, so again it’s no surprise that mystery aircraft weren’t seen to be hostile. The more difficult cases are in 1909 and, to a lesser extent, 1938. In 1909, the mystery aircraft were the object of curiosity, not suspicion. But that same year Britain was undergoing every sort of defence panic around: invasion, dreadnoughts, airships, spies. Australians were also very worried about invasion, albeit from Japan, not Germany. Why didn’t Australians imagine Japanese airships spying from overhead, preparing the way for the Emperor’s soldiers?

The answer must have something to do with perceived plausibility, which in turn depends on perceived capability and perceived intent. In 1909, Germany had Zeppelins; Japan had nothing. If Japan had been publicly and successfully experimenting with longrange aircraft in like fashion to Germany, then Australians might have believed that the 1909 mystery airships were Japanese, just as Britons believed that theirs were German.7 In 1938, things were different. Everyone had aircraft now; and Japan was closer, in the sense that it had forward bases in Micronesia as well as aircraft carriers. It was now plausible to imagine that Japanese aircraft could reach Australia.

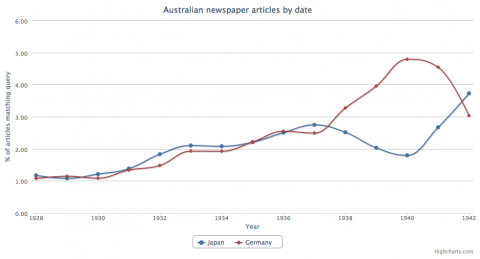

I was going to suggest that it was also now more plausible to imagine that Japan intended to attack Australia: after the Marco Polo Bridge incident in 1937 (and setting aside the invasion of Manchuria in 1931 which seems to have made less of an impression) it was clearly in an aggressive, expansionist phase. But the above plot suggests that press interest, at least, in Japan actually declined after 1937. That’s a very crude index, of course, but it’s consistent with Augustine Meaher’s argument that Australians were surprisingly unconcerned about Japan in the late 1930s, contrary to Peter Stanley’s view.

This is starting to get confusing. But, paradoxically, considering another problem with mystery aircraft may help here. Why were there no big waves of mystery aircraft sightings after the First World War? This seems to be true worldwide. Between 1896 and 1918 there were a number of times where mystery aircraft are seen in many places by many people over a short period of time: the United States, Canada, Britain, New Zealand, Australia.8 Afterwards, while there were certainly mystery aircraft sightings, they tended to occur singly, appearing once or twice at one place and then disappearing.9 They were also interpreted in isolation: nobody seems to have connected the Hobart mystery aeroplane of July 1938 with the Darwin case in February, nobody saw them as part of the same phenomenon. I’m not sure why this is, but I suspect that a greater familiarity with real aircraft must have had something to do with it. Actual aircraft were very rare in all countries when mystery aircraft waves took place: airships and aeroplanes were imagined far more than seen. This ignorance made it easier to believe that a planet, a fire-balloon or a Reticulan battlecruiser was in fact a aeroplane: easier for the witnesses, easier for everyone they told to believe them, easier for the journalists covered the story to treat it seriously. The spread of the idea that Germans (etc) were flying around in the sky met no resistance — at least for a while: when the press starts to get sceptical the mystery aircraft waves tend to collapse very quickly.

So, while the huge increase in flying in Australia from the late 1920s may have put aviation at the forefront of the national consciousness and provided imaginative fodder for mystery aircraft incidents, it seems to have provided an inoculation against mass waves of sightings. For that to occur there needed to be plausibility, curiosity, and ignorance. All three at once. Mystery aircraft do appear at other times, but don’t lead to anything else and are soon forgotten.

I’m not happy with this post; it’s long and rambling, unfocused and confusing. Partly that’s due to me making it up as I go along rather than planning ahead; but it’s also partly due to the fuzzy nature of the mystery aeroplane phenomenon (and indeed history) itself. In trying to find common factors and causes I run the risk of imposing my own order where there is none. Maybe there is really no point to this. Maybe the Scareship Age was no such thing. So people thought they saw aircraft flying around where they were none. So what? Sometimes I think I should focus my research on phantom airships and mystery aeroplanes: it’s something that few other historians are interested in and so it’s one area where I can make a distinctive contribution. But then again, maybe there’s a reason why it’s a fallow field.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Of course, part of the 1909 data in the ngram above is from the airship sightings. But not many. [↩]

- ‘Plane’ is not as good a word for datamining as ‘aeroplane’, because it has other meanings, in geometry and carpentry for example. It’s also more likely to show up as an OCR error, e.g. for ‘place’, than ‘aeroplane’ is. It can also appear as ‘-plane’, that is to say when a typesetter breaks a word over two lines; but the vast majority of those would have been ‘aeroplane’ anyway. Still, the aviation meaning is the most common one, as you can see from how closely it tracks ‘aeroplane’ until the mid-1930s. [↩]

- 60,000 people turned out to see Cobham land; 26,000 to see Smithy and Ulm. [↩]

- Hinkler, Kingsford-Smith and Ulm were all killed attempting long-distance flights, though not for a few more years. [↩]

- I’ve extracted the data for this and the next plot from the Official Year Book of the Commonwealth of Australia series, which first recorded civil aviation statistics in the 1922 edition. The data is for the year ending 30 June. [↩]

- The average length of a flight was very low, e.g. in 1930 only 20 minutes. That suggests that the majority were joyflights; but Edmonds says that the barnstorming phase in Australian aviation was pretty much over by 1921. [↩]

- Having said that, a 1909 Japanese invasion play by Randolph Bedford’s, unsubtly entitled White Australia, or The Empty North, does revolve around an airship with great destructive powers. However, in this case the airship is an Australian invention which a Japanese spy tries (unsuccessfully, you’ll be glad to know) to steal for use in bombing Sydney. I’ve read the script, and it’s just as bad as you think. See the review in the Argus (Melbourne), 28 June 1909, 9. The airship itself can just be made out in the play’s advertising poster. [↩]

- All English-speaking countries, though I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s simply my ignorance as an monophone. [↩]

- At least, before Sweden in 1946 they did. Or perhaps the foo fighters over Europe during the war, though there the context was very different. [↩]

Hi Brett

A very nice series of articles if I may say so. You seem too be worried about focus but this actually is not an easy phenomenon to define and research.

What is clear about scareships is that they were a global phenomenon not just an Australian one and as such shared characteristics. It also seems that they were mostly observed in rural or sparsely populated areas and given the size of the Australian population then and remoteness of settlements it is unsurprising that there are so few reports. It requires an individual to be sufficiently motivated or confident to mention the experience, the news to get to a newspaper which is sufficiently interested to report the sighting and as a result the possibility exists that some observers did not report their sightings or that they were not reported in the press.

The scareship phenomenon has been rather appropriated by the UFO crowd who come up with all sorts of speculation about their origins. This is probably why most historians avoid the topic – one doesn’t want to risk one’s reputation being associated with the wilder reaches of human speculation.

Thanks, Christopher! The reason why I worry about focus is that I’m thinking ahead. If I ever get close to getting an academic job, one question I will need to answer is “what next?”, and filling in the corners of your PhD is not looked upon favourably. Also, there’s the (also remote) possibility of applying for research or travel grants or even fellowships. I’d need to have very clear objectives for that. So what I worry about is whether the mystery aircraft thing is worth pursuing in this regard, or whether it’s best done on the side. As you note, it’s tainted by association with ufology to some degree. That’s one reason why I’d like to rescue it (Alfred Gollin made a start with the British phantom airship waves, though nobody has really followed this up; Robert Bartholomew has also written about mystery aircraft panics from a sociological point of view). But it’s also perhaps a reason why I should stay away, if I hope to get anywhere with the academy.

The process you describe is something like the one I envisage happening. People saw something odd in the sky, maybe thought nothing of it, maybe thought it was an aircraft of some sort. Then, maybe they told somebody, maybe they didn’t. Maybe a newspaper decided it was newsworthy, maybe not. There are quite a few of these (actually, it looks like they were more common overall in Australia than say, Britain, though that’s probably because of the superlative ease with which Australian newspapers can be searched), but it’s when things start going meta that I think it gets really interesting — when it takes off and becomes a mass phenomenon. The press is clearly key in this process, though not necessarily in a straightforward way: in 1918, the vast majority of sightings (about 150 in total) were not reported in the press, only to the authorities. It was more the speculations about the aerial threat from German raiders off the coast combined with a few sighting reports that seems to have kicked things off. That suggests that as you say, probably most sightings went unreported in the press.

Actually, re-reading your comment I misread what you meant by ‘focus’ in this context — sorry!

Pingback: discontents - For you, with all best wishes…