The Twenty-Fifth Hour (1940), by Herbert Best (better known as the author of the ‘Desmond the dog detective’ books, though not by much), may well be the last knock-out blow novel, the last novel where (conventional) bombers play the decisive part in a war. In this war, indeed, they are too decisive, knocking away the underpinnings of modern life and destroying civilisation. I don’t know for sure that it is the last, but it was published right before the Blitz (it was the Times Literary Supplement‘s pick of the week for 24 August 1940) and it’s hard to imagine any more attempts to visualise the knock-out blow after that. I could be (and would love to be) wrong, though. It certainly presents a very late example of the genre, and so it’s worth examining its vision of war.

The novel is set several years after the war (which is evidently not the Second World War), after European society has broken down, and so we only get a fragmentary picture of what actually happened, through characters’ memories; and even they did not fully comprehend the chain of events which destroyed the old world. The one which replaced it is grim indeed, with roving bands of ex-soldiers raping and pillaging their way across Europe in the aftermath of the war proper, followed by the gradual elimination of even this vestige of order. Agriculture is soon impossible, and wild game is too few to sustain the population which survived the war (overpopulation seems to be Best’s overarching theme; he sees it as a key cause of war). Cannibalism is the only solution, leading inevitably to the near-impossibility of sustaining any group larger than a single individual. Only in a few places is this possible, for example in fortifications in north-west Europe (perhaps the Maginot Line) and in Gibraltar; in empty Istanbul two Englishmen strike up a brief alliance (well, they are both Oxbridge men). But the emphasis is very much on the bleakness of post-apocalyptic life: only the strong, the smart and the fortunate can survive; everyone else is food.

As far as it can be pieced together, then, the war — which seems to take place in the mid-1940s or 1950s — went like this. It was begun by Russia ‘with fighting on her east and south-west borders’1, and involved Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Spain and Denmark, among others. There is little news of the Americas ‘except an early rumour that germ warfare had broken out in Brazil’.2 Soon the bombing began: ‘Rome had burned in very truth, Rome, Paris, London and a hundred other cities, in one simultaneous conflagration’.3

Already the important cities and the munition centres had been burned out by air attacks, by reprisal following upon reprisal until each side could claim each new act of terrorism an act of justifiable and righteous vengeance. For technical reasons the air forces of the world were formed of bombers, not fighters; planned for offence, not defence. The terrorizing of civilians, not the killing of fighting men, was the accepted aim. One air force attacked and was met by no air defence. The opposing air force retaliated by bombing, spraying, gassing and burning out the civilians of the first power. The theory was that your own civilians would stand up under the slaughter, but that the enemy civilians would be broken in morale and disorganized. If they did not immediately sue for peace, their factories and munition works would be unable to make good the wastage in planes and engines, replace the stores of oil, gasolene [sic], high explosives, lethal gases.4

As for the other arms, ‘The air strategy of “offence-not-defence” had been imposed on both armies and navies with the result that nations abandoned their Maginot and Siegfried lines’.5

Armies, actuated by this ‘spirit of the new offensive’, marched, but made no attempt to hold their elaborate defence lines nor to make contact with the enemy and fight for decisive victory. Their function was to occupy enemy territory, to wipe out the ground equipment of the enemy bombers while their own bombers increased the disorganization of the enemy state.6

Fitzharding, one of the protagonists, fought as a lieutenant in Britain’s ‘new Air Auxiliary Infantry’.7 Near the end of the war proper, he took part in a company-sized airborne night assault against ‘a German bombing base in enemy-occupied Holland’.6 This was around the time that ‘one of the later air raids had liquidated the Civilian Administrator [of Britain] and all his emergency staff of government’.8 From this point,

Nations were ceasing to be nations. That [the airborne assault] must have been one of the last organized movements ordered by the British Government before it melted out of existence. For, ironically enough, the new system of warfare upon civilians, ‘realistic warfare’, it had been called at the time, proved too efficient. Nations were too disorganized to sue for peace. Troops, well in the heart of each other’s country, found their home communications gone, no instructions, no supplies, no ammunition. Desperate civilians were burning large tracts of country, removing anything eatable that they could find, poisoning wells with dead bodies, while armies broke into corps, into divisions, into smaller and smaller units which, living on the land, sought to percolate back home. Now, more than ever, enemy forces avoided each other. There was no time for the luxury of fighting pointless battles […]9

As The Twenty-Fifth Hour begins, Fitzharding is leading one of these military remnants, wandering somewhere in a snowbound eastern Europe, planning an attack against a château which has warmth, food, and women. Some years later he is alone, hunting and hunted, until he meets the other Oxbridge man, a former Foreign Office attaché who muses on the end of civilisation:

the destruction of communications, leaving people concentrated in rings around bombed-out cities, millions of them. And all the elaborate organizations which gave them water, light, food and their daily necessities gone, wiped out. Army corps dependent on long lines of communication for munitions, fuel, oil, food, and these communications gone. Even the fundamental agriculture on machinery, fertilizers, oil fuel, not living on what it produced, but needing to exchange sugar-beets or rye or wheat or even cattle for the farmers’ necessities of life. Everybody dependent on everybody else and communications gone.10

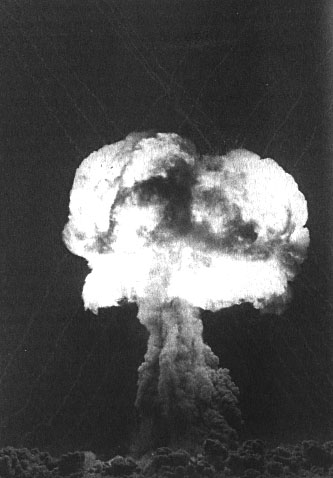

All of this is an utterly classic knock-out blow scenario, which could easily have been written a decade earlier (in outline it’s very reminiscent of H. G. Wells’s The Shape of Things to Come, though much less didactic, more interesting as a novel). The mystery is why it was published so late. Knock-out blow novels dried up in the last years before the war, as the government’s military and civil defence preparations bore fruit, and experts re-evaluated their belief that effective air defence was impossible. Part of the answer, I think, is that Best was writing about the next war from the perspective of the current one (presumably after a negotiated peace). The prominent references to paratroops almost certainly date the writing of the book to after May 1940, as does the dismissive reference to the Maginot Line. From mid-1940, the rapid conquest of France and the low countries certainly appeared to restore the mobility of armies after the long stalemates of 1914-8. Best was extrapolating that trend into the future to an extreme fluidity, a complete lack of front lines. He evidently viewed this as pointing in the same direction as bombing, i.e. towards the objective of completely disorganising the enemy home front. Unfortunately, in the next war (perhaps with more and bigger bombers, though Best doesn’t discuss this), bombing simply becomes too effective at destruction for civilisation to survive. Thus The Twenty-Fifth Hour, the last of the knock-out blow novels, and one of the few post-apocalyptic ones, neatly prefigures the later nuclear warfare novels.11

The Twenty-Fifth Hour is a pretty good read. Although it’s obviously quite gloomy, without giving away the ending I will suggest that the title gives reason for hope: the twenty-fifth hour is the first hour of a new day.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Herbert Best, The Twenty-Fifth Hour (London: Jonathan Cape, 1940), 40. [↩]

- Ibid. Much of the novel is in fact set in the United States, which is not involved in the war. However, it undergoes another Depression, psychological as much as financial. But eventually ships from Europe do bring a plague which apparently wipes out life throughout the Americas. [↩]

- Ibid., 53. [↩]

- Ibid., 37-8. [↩]

- Ibid., 178. [↩]

- Ibid., 38. [↩] [↩]

- Ibid., 37. [↩]

- Ibid., 179. [↩]

- Ibid., 39-40. [↩]

- Ibid., 179-80. [↩]

- For that matter, knock-out blow novels are probably the true ancestors of the post-Hiroshima atom bomb stories, more than the few pre-1945 stories which just happened to feature atomic bombs. [↩]

Maybe he just wanted to write a book with lots of cannibalism in it? You’ll never think of Desmond the dog detective the same way again!

And while it has been a long time since I’ve read it, Andre Norton’s Quest Crosstime has the protagonist briefly visit a post-apocalyptic world where the turning point seems to have been conventional bombing in 1940/1. Though I can’t guarantee that there weren’t nukes in it.

Well, that’s not good enough. I demand a guarantee!