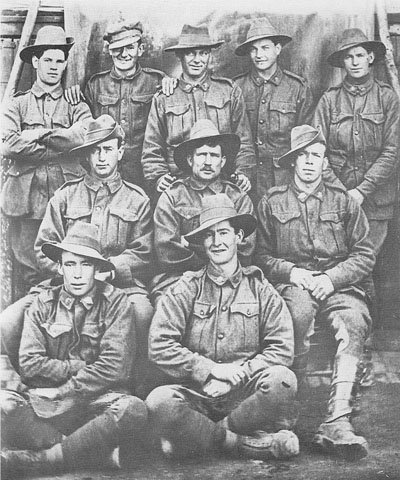

This photograph of Australian soldiers was taken during the First World War. It’s not particularly unusual: just a group of mates getting together to record a memento, perhaps after a weekend’s carousing in the fleshpots of Cairo or Paris.

Mateship is a important concept in Australian culture. The OED defines it as ‘The condition of being a mate; companionship, fellowship, comradeship’ and notes that it is ‘Now chiefly Austral. and N.Z.’ The Australian National Dictionary gives several more specifically Australian shades of meaning, from ‘An acquaintance; a person engaged in the same activity’, to ‘One with whom the bonds of close friendship are acknowledged, a “sworn friend”‘, to ‘A mode of address implying equality and goodwill; freq. used to a casual acquaintance and, esp. in recent use […], ironic’. Suffice it to say that pretty much any bloke can have occasion to call another cobber a mate, whether they are good friends or bitter enemies. (Sheilas are another question, of course.)

Mateship is a positive virtue. As C. E. W. Bean wrote in 1921, in the first volume (page 6) of his official history of Australia in the Great War:

The typical Australian […] was seldom religious in the sense in which the word is generally used. So far as he held a prevailing creed, it was a romantic one inherited from the gold-miner and the bush-man, of which the chief article was that a man should at all times and at any cost stand by his mate. This was and is the one law which the good Australian must never break. It is bred in the child and stays with him through life.

Mateship also has strong military resonances, as Bean’s interest in it might suggest. An Army News article on the unveiling of a war memorial in Papua New Guinea commemorating the Kokoda Track, the site of bitter fighting between Australians and Japanese in 1942, notes that the words courage, mateship, endurance and sacrifice are inscribed on its pillars. It further adds that these are ‘words that today’s Australian Army has built its foundations on’. So mateship is both an expression of Australia’s egalitarian spirit and its martial one, as former Prime Minister John Howard explained in a speech given at Australia House in London in 2003:

The two world wars exacted a terrible price from us — the full magnitude of that lost potential, of those unlived lives can never be measured. And yet, some of the most admirable aspects of Australia’s national character were, if not conceived, then more fully ingrained within us by the searing experiences of those conflicts.

None more so than the concept of mateship — regarded as a particularly Australian virtue — a concept that encompasses unconditional acceptance, mutual and self respect, sharing whatever is available no matter how meagre, a concept based on trust and selflessness and absolute interdependence. In combat, men did live and die by its creed. ‘Sticking by your mates’ was sometimes the only reason for continuing on when all seemed hopeless.

I was moved by an account written by Hugh Clarke, who, like thousands of other Australian and British servicemen, endured years of senseless cruelty as a prisoner of the Japanese after the fall of Singapore. He couldn’t recall a single Australian dying alone without someone being there to look after him in some way. That’s mateship.

Contemporary Australia takes great pride in its egalitarian attitudes. Mud and fear and enemy fire are no respecters of class, rank or parentage and from both wars, our veterans brought back to Australian society a renewed conviction that an individual’s worth should be judged — not by those things — but by their own talent, courage and personal virtue.

Howard was particularly fond of the concept of mateship; in 1999 he even tried to get it inserted into the preamble of the Australian constitution. It was in fact one of the sites of conflict in Australia’s culture wars of the late 1990s and early 2000s: Marilyn Lake has criticised it as reinforcing white solidarity. She has a point; and it’s not like Australia is the only country in the world to value mateship, even if it isn’t called that. (Although one of the more charming aspects of the word ‘mate’ is the way it’s quickly picked up and used by new arrivals to these shores.) Gender critiques are even more pointed: while women can and do use the word, and can be mates with men and and with each other, it still has a blokey feel. Idealising mateship as an inherently Australian trait is exclusionary, as Martin Ball has argued for the related concept of the ‘Anzac spirit’:

The Anzac tradition holds many values for us all to celebrate, but the myth also suppresses parts of Australian history that are difficult to deal with. Anzac is a means of forgetting the origins of Australia. The Aboriginal population is conveniently absent. The convict stain is wiped clean. Postwar immigration is yet to broaden the cultural identity of the population. […] The problem with the simple patriotism of Anzac is that it runs the risk of making some of us are more Australian than others.

Which brings me back to the photograph at the start of the post. It actually isn’t as straightforward as it seems. The men pictured are actually all deserters; and the reason they posed for the photograph was to taunt the military authorities they had escaped from. For it was sent to the Australian Assistant Provost Marshal in Le Havre, along with the following letter:

Sir,

With all due respect we send you this P. C. [post card] as a souvenir trusting that you will keep it as a mark of esteem from those who know you well. At the same time trusting that Nous jamais regardez vous encore [we will never see you again]. Au revoir.

Nous

The deserters — who were apparently never caught — are displaying mateship, humour, larrikinism and all those good things which are supposedly part of the Australian essence, but deployed in a way that cuts against the celebration of the Anzac spirit. For whatever reason, these men who had all volunteered for war decided to have nothing more to do with it, and so could be considered to be some of the first war resisters in Australian history.

NB. The photograph comes ultimately from the Australian War Memorial, but I found it in Ashley Ekins, ed., 1918 Year of Victory: The End of the Great War and the Shaping of History (Titirangi and Wollombi: Exisle Publishing, 2010). Ekins’ own essay in that book on ‘morale, discipline and combat effectiveness’ has much to say on this topic, though unfortunately doesn’t specifically discuss our ten mates above.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

I had to laugh when I saw that cheeky photograph in the Ekins book!

Whilst I hold with Prof. Lake on much of her critique of Australian militarism – I don’t think that mateship, and particularly military mateship reinforces white solidarity.

In the book The black diggers: Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders in the Second World War by Robert A. Hall, (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1989); there are several anecdotal examples of black diggers being shown care and friendship by their white comrades-in-arms. A care and friendship which was not such a large part of wider Australian society at the time – and furthermore a care and friendship which was extended to the post-war period as black diggers were quoted recounting warm reunions with their white wartime mates in later years both in organised and unorganised settings.

The book is not to hand so I can’t give you page references.

Ah yes, the uniquely Australian virtue of friendship.

A great photo and an amazing story.

I thought you’d lost the plot for the first 3/4 of the post. Well done.

Even if they hadn’t turned out to be deserters, the photo nicely illustrates the white male bias of military mateship. Women weren’t allowed to volunteer to fight. In Britain they weren’t even allowed to vote in parliamentary elections for most of the First World War. I’ve just checked Wikipedia to see what the situation was in Australia and I’m quite surprised that although white women could vote in Commonwealth Parliament elections from 1902, Aboriginal men and women couldn’t until 1966!

John Howard, surely, is the last person on earth anyone would call a mate….mate.

Bob:

Exactly my reaction when I saw it! That’s why I had to blog it.

Sounds like an interesting book. I think it shows that the value of mateship is outside the institutionalised version that Howard and perhaps the armed forces would like.

Heath:

I think the only thing that’s unique about mateship is how unique we think it is …

JDK:

I’m glad you kept reading!

Gavin:

On that it’s worth pointing out that Australia now has its first female prime minister (though installed by internal party politics, not by a federal election) — it only took us 108 years. Perhaps we can have an indigenous head of state before 2074.

Alex:

Ah, but that’s the thing about the word ‘mate’, you don’t actually have to be mates with someone to call them mate. It’s the great leveller.

I’d be curious to know whether military mateship has ever been criticized for its parochialism. One of the complaints levelled against British soldiers in the period of the two world wars was that their attachment to their particular narrowly defined ‘mob’ precluded any wider sympathy for or interest in the larger corporate structures of the army – the ‘f**k you jack, I’m alright’ phenomenon. Soldiers were criticized for being insufficiently interested in the success of their brigades, divisions or corps so long as the regimental battalion put up a good battle performance.

Hall’s style of writing is not particularly literary, but his book The black diggers has some facts and anecdotes not otherwise available.

Alan:

I don’t know (and wouldn’t be the person to ask!). Dale Blair’s Dinkum Diggers (a study of a single AIF battalion) might have something on that. But in the Ekins volume, Tim Cook makes the point (for the Canadians, but it also applies to the Australians) that they had a much stronger corps identity than British formations — obviously because of the national aspect, but also because British divisions (and I guess smaller units) were rotated through corps-level formations very frequently.

Pingback: Airminded · Acquisitions

Pingback: Airminded · As it was

Pingback: The one day of the century | Airminded