The RAAF Museum, round 2. This time there was less time spent outside looking at aeroplanes in the air (above, see below) and more inside looking at aeroplanes (and other things) on the ground (see below).

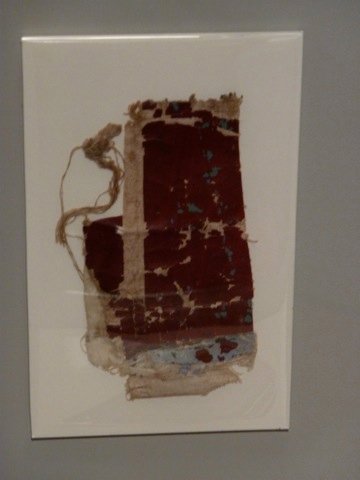

A precious relic: a piece of the true crossfabric from the Red Baron’s Fokker Dr.I. Why is it here? Because it was ‘souvenired’ (as the display puts it) by members of No. 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC). Richthofen was shot down in No. 3 Squadron’s sector, probably by Australian gunners, and they had responsibility for his body and aircraft.

The AFC was the Australian army’s first aviation unit, founded in 1912 at Point Cook — the same year as the RFC, incidentally. (Technically, only the Central Flying School was established in 1912; references to the AFC don’t appear until 1914. But what is a flying school without a flying corps?) It fielded four squadrons in Palestine and France. One of these was No. 4 Squadron, which was also part of the British forces occupying Germany until March 1919. This is part of an Australian flag (i.e. the British part), created to commemorate the end of the First World War and No 4 Squadron’s role in it. Supposedly it was ‘the first Australian flag flown into Germany 10.45am 7 12 18’ (ie 7 December 1918).

Another Australian flag from 1919. This one is a red ensign (with Australia and the British Isles superimposed — note the still-united Ireland), which at the time was used almost as widely as the more familiar national ensign. It was presented to Ross Smith when he, along with his brother Keith, Jim Bennett and Wally Shears landed at Darwin and became the first to fly from London to Australia in less than 30 days. A nice little earner as it netted them £10,000 from the Australian government. All of them were RFC/AFC/RAF veterans and they flew a Vimy, the same type which bridged the Atlantic the same year.

Something I don’t think I’ve ever seen before: window!

It may seem odd, given their great distance from anywhere, but Australians had to undertake air raid precautions just as people living closer to the front line did. Well, not quite the same: Melbourne had a brownout instead of a blackout, for example. I haven’t read this book, but most ARP advice in Australia was derived from British theory and experience, and this one was probably much the same.

The turret from a Bristol Beaufort, sporting twin .303 Browning machine-guns. You can just make out the seat in the middle of the hydraulics, which gives an idea of just how cramped it was for the unfortunate gunner.

A crumpled metal case belong to Sister Marie Craig, a RAAF nurse. She, along with 29 other people, was killed on 18 September 1945 when the RAAF Dakota they were flying on crashed in West Papua.

A flag taken from the Viet Cong near Long Tan, the scene of a hard-fought Australian victory during the Vietnam war. RAAF helicopters resupplied Australian troops from the air during the battle.

This is one of those helicopters, a Bell Iroquois. The RAAF operated helicopters in tactical support of the Army until 1986, a job the Army now does itself.

And with that we’ve smoothly segued into the static aircraft displays. One of the first things you see is this Macchi MB-326. The Macchis were used for advanced training, and were also very familiar as the type flown by the Roulettes, the RAAF’s aerobatic team, for nearly two decades.

A Link Trainer, an early form of flight simulator, used in the 1930s and 1940s. Nothing terribly special about that, lots of museums have them …

… but as JDK pointed out, the accompanying control desk for the instructor is a lot rarer. The instrument panel of the Link was duplicated in front of the instructor, and a mechanical ‘crab’ marked the progress of the pilot’s simulated flight on a map.

The RAAF’s first dedicated trainer was the Maurice Farman Shorthorn. This particular aircraft was purchased in 1917 and was only in air force service for two years. A civilian pilot used it for joyflights into the 1930s; the remains were donated to the RAAF Museum in 1981 and eventually restored to the splendid state it is in today. Which raises the question of whether it is actually appropriate to identify this object with the machine the RAAF bought in 1917? Only 30% of its components are original, meaning that 70% are not (i.e sourced from another aircraft or scratch-built). Obviously we’d like to believe that vintage aircraft are the ‘real’ thing, but they’re always reconstructions to a greater or lesser extent.

Flying Vampires, the Telstars were the predecessors of the Roulettes. Such a 1960s name.

There’s no doubt about the authenticity of this Avro 504K: it’s all replica. But a very nice one.

A splendid example of the Supermarine Walrus, a ubiquitous amphibian of the late 1930s and 1940s. This one (okay, some of this one … it is just easier to drop the qualifiers) is in the colours it had during an Australian Antarctic expedition in 1947. It was wrecked on Heard Island after only one flight, and not recovered until 1980.

The Walrus was in fact designed in response to a RAAF specification, for catapult launch from Royal Australian Navy cruisers. The British and Canadian navies liked them too, though they ended being used more for search and rescue than gunnery spotting, the original purpose. A pretty rugged aeroplane, it could supposedly do outside loops (though probably not something you’d want to try if it had been shipping water!)

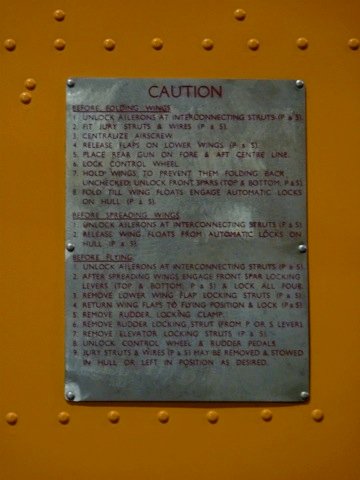

Some handy hints for the Walrus operator.

A Vampire in bumblebee colours, used as a target tug.

An example of the kind of target it would have towed, incomplete with bullet holes.

The Dassault Mirage III, the RAAF’s interceptor from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. (When I say ‘the’, there was more than one, okay? Don’t be so literal-minded. Sheesh.) It was the main type operating by the RAAF when I was growing up — the Hornet which replaced it still seems new to me.

A Douglas Boston bomber, also known as the Havoc. The last remaining Boston III, it’s looking pretty good for something which spent half a century rusting away. It crashed on landing at Goodenough Island, near Papua New Guinea, on 12 December 1943.

Three times a week, the RAAF Museum holds a flying display, where one of its vintage aircraft gets out of the hangar and into the sky. This makes it fairly unusual among aviation museums; running these things is not cheap. On the day that JDK and I were there, we and the other visitors were treated to some tumbles and turns from a CAC Mustang flown by an airline pilot on his day off. I’m grateful for his sacrifice!

It could be said that putting its artifacts at risk like this is somewhat at odds with a museum’s primary mission, to preserve the heritage of [whatever] for future generations. Even the best maintained and piloted aeroplanes have accidents, and it would be a terrible shame if one of these machines were destroyed in such a way (not to mention the risk to the pilot). Of course, the Museum is aware of this, and has a policy that it will only fly aircraft where it has more than one example: one flying and one spare, in effect. But it’s also worth remembering that technology is meant to be used. A static display in a museum can only tell people so much. Showing them how the machine works — and, too, the acts of restoring it, maintaining it, and flying it — aids in understanding it in a fuller context. Of course that can only be taken so far: it probably wouldn’t be a good idea to load up the Mustang with rockets and take it on strafing runs. But it’s a step.

And speaking of heritage, behind the taxiing Mustang above can be seen some of Point Cook’s original hangars and buildings, the oldest dating back to 1914. In fact, this may be the most complete First World War-era military aerodrome anywhere in the world, an amazing survival. But they are not open to visitors, they are not being used and they are not being maintained. The RAAF Museum (unlike its British counterpart) is part of the air force it represents. This means it has a fairly secure budget and access to resources an independent museum might not other have. But it also means that, as part of the military, it is constrained about seeking funding from outside sources and can’t just do as it likes with government property (Point Cook is actually still part of an air force base, RAAF Williams). The buildings are heritage listed, but all this means is that they can’t be pulled down or modified without planning authority approval first. Obviously the RAAF has other priorities when it comes to spending money, but it’s a crying shame that more isn’t being done with these priceless buildings.

That’s enough ranting for now! Here’s another part of the museum which is rarely seen, one of the workshops. Closest to the camera is the some of the wood from a wooden wonder: the nose of a de Havilland Mosquito undergoing restoration. In the background is a very interesting project, a replica of a Bristol Boxkite, the very first Australian military aeroplane. The aim is to get this in the air by 2014, the centenary of the first flight in Australian service, and it looks like it’s well on the way to meeting the deadline. I had an interesting chat with the guys putting it together, and resisted the urge to ask how quickly they’d be able to scale up production in case the JSF is delayed.

(Thanks to JDK for this picture and the Mustang at the top of the post!)

Last hangar of the day, Hangar 180. It is actually just a hangar with the aircraft lined up inside; you can’t get up close to them, but it’s an economical way of putting them where people can see them, instead of storing them. The white object in the middle here is a GAF Jindivik target drone, which was developed by Australia in the late 1940s to help with Britain’s missile development programmes. Quite a successful machine, it first flew in 1952 and was still in use in the 1980s, but it didn’t lead to any long term Australian expertise in drone technology: today we buy ours from the United States.

Behind is a Hawker Demon, a CAC Sabre and the fuselage of a Consolidated PBY Catalina.

This is a rare bird indeed, a GAF Pika, the manned prototype of the Jindivik. Only two were built.

A Westland Wapiti. These general purpose aircraft first flew in 1928, and served widely with Commonwealth air forces. If you wanted to bomb subject peoples in the outer reaches of Empire, this is what you’d use.

Update: The preceding paragraph is all very interesting but, as JDK has pointed out, it’s actually an Avro Cadet, which looks somewhat similar, but came a bit later and was a trainer rather than a front-line aircraft. Let that be a lesson to anyone who believes everything I write!

A Sikorsky Dragonfly, one of the first practical helicopters (first flight 1943). It must have looked so ungainly next to, well, just about anything else flying. I think the concept has been proved by now, though.

Let’s end here with a Boomerang. Thanks again to JDK for providing carlift and expert commentary!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.