Later the same day that I arrived at Heathrow and visited Salisbury, I was down in the southwest of England — Exeter, to be precise. I was there for a conference but arrived a day early so I could have a poke around. There are indeed some things very worth seeing in Exeter, although the city centre was very heavily blitzed on 4 May 1942, destroying many fine historic buildings. Above is a stained glass window in Exeter Cathedral commemorating that night.

The cathedral itself was hit by a bomb which destroyed St James Chapel, two buttresses and several windows, and left scars which can still be seen today. (If memory serves, I think the damage seen on these interior columns was caused by secondary splinters from the chapel.)

Otherwise, the cathedral escaped the war relatively intact, which is just as well because it’s a treasure. The tower above, was built in the Norman style and in the Norman period: it (and its near-twin on the other side) dates to the 12th century.

The rest of the cathedral was rebuilt in the following century in the Gothic style, which allowed for an airy vaulted ceiling and moreover was bang up-to-date.

A figure (St George?) over a doorway on the north side. It looks very well preserved so I suspect it’s not actually very old or at least has been restored (unlike the statues guarding the Great West Door, which were carved over six hundred years ago but which, for some reason, I neglected to photograph).

The cathedral close — well, the lawn bit of it anyway — is evidently a popular place to sit and soak up the sunshine. This area also largely escaped the Blitz, and has some very pleasant little cafes and pubs.

As impressive as it is on the outside, only from the inside can you fully appreciate the beauty of Exeter Cathedral. Because, unlike most cathedrals (certainly most I’ve been to), there is no central tower, the rebuilding gave Exter the longest vaulted ceiling in England.

Another view of the ceiling, looking west.

A close-up of the most famous boss, which depicts the martyrdom of St Thomas Becket. Doesn’t look very big from way down here, but it weighs two tonnes. Its height enabled it to survive Henry VIII. It was repainted in 1975, but much of the original paint did survive at that time to guide conservators, so it would have looked something like this in the 13th century.

The view towards the Great East Window, installed in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Being highly vulnerable to blast from high explosive, it was removed for safekeeping during the war and thus is the only medieval window left.

The choir (or quire), which happens to be where the choir sits. The misericords (benches to lean against during long services, like you often see in public transport these days) in the stalls are the oldest complete set in England and date from as far back as 1220. Note also the organ rising above.

A priest raising his arms to heaven, from the end of one of the choir stalls.

A still-working astronomical clock from made in the late 15th century (except for the 18th century minute hand at the top). It shows the position of the Sun and the Moon and the phase of the latter. PEREUNT ET IMPUTANTUR is from Martial and means ‘they [the hours] perish and are reckoned to our account’, so my wiki Latin tells me. To the right is a late medieval painting depicting the resurrection of Christ.

This is part of a wonderful sculpture made in the Netherlands around 1500 (but arriving in Exeter much more recently), depicting the crucifixion (you can just make out the three crosses at the top of the photo). The two grieving Marys are there, the Blessed Virgin Mary being physically supported by her friends and Mary Magdalene (long golden hair, brazenly uncovered, ergo a prostitute) stretching out her arms as if to touch Jesus. A very humane scene.

British Army battle honours. The tradition is that these remain on display until they disintegrate. These are from the 20th Regiment of Foot (the East Devonshire Regiment, later the Lancashire Fusiliers), I think from the battle of Inkerman in 1854?

Of course, one thing any decent cathedral has is tombs and memorials, and Exeter is no exception. Here are Margaret de Bohun (died 1391) and her husband Hugh de Courtenay (died 1377), Earl of Devon. She was a granddaughter of Edward I and he was a veteran of Poitiers.

Remember, thou art mortal. Actually, I think that’s the whole point of this: it doesn’t seem to be a tomb at all.

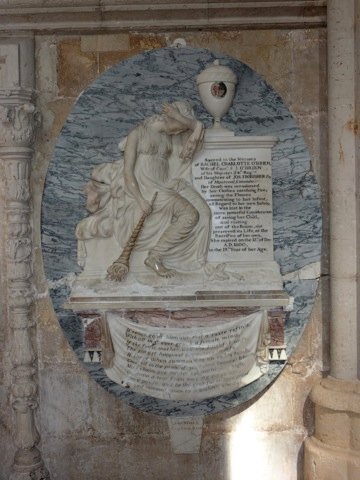

Sacred to the Memory

of RACHEL CHARLOTTE O’BRIEN,

Wife of Capt.n E. J. O’BRIEN

of his Majesty’s 24.th Reg.mt

and Daught of JOS. FROBISHER Esq.

of Montreal, Canada.

Her Death was occasioned

by her Clothes catching Fire;

seeing the Flames

communicating to her Infant,

All Regard to her own Safety,

was lost in the

more powerful Consideration

of saving her Child,

and rushing

out of the Room, she

preserved its Life, at the

Sacrifice of her own.

She expired on the 13.th of Dec.

A.D.1800,

in the 19.th Year of her Age.If sense, good humour, and a taste refin’d,

With all that ever grac’d a female mind,

If the fond mother, and the faithful wife,

The purest happiest characters in life,

If these when summon’d to an early tomb,

Cloath’d in the pride of youth, and beauty’s bloom,

May claim one tender sympathizing sigh,

Or draw a tear from melting pity’s eye,

Here pause, and be the grateful tribute paid

In sad remembrance to O’BRIEN’s shade!J. KENDALL

Longbrook Street

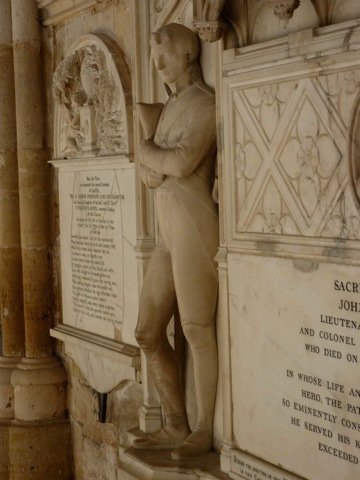

A memorial to General John Simcoe, who died in 1806: a veteran of the American Revolutionary War (on the losing side, of course) who was later lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada (he founded Toronto).

The tomb of Lady Dorothy Dodderidge (died 1614), wife of Sir John Dodderidge and daughter of Sir Amias Bampfylde. No, really!

Look at the loving attention to detail in this skull, from another Tudor tomb. That’s craftsmanship, that is. You wouldn’t get that on a tomb these days.

The other big attraction in Exeter is the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, which sounds like the perfect rambly old museum. But sadly it’s closed until 2010 or 2011 for a refurbishment. But there are other things to see. This is St Petrock’s Church, which dates to no later than the 1190s. Certainly the lower parts are 12th century, but the tower is 15th century. The windows are blocked up because until 1905 it was stuck behind a row of houses.

The remains of the medieval bridge over the Exe, built around 1200. One of the oldest bridges in Britain, it had houses on it, and a church, St Edmunds. The tower at the far end belongs to St Edmunds: it’s not a medieval ruin but was in the process of being demolished when the bridge was discovered!

A more modern bridge over the Exe, from the vantage point of the 16th century quay.

The Custom House, built in 1680-1 and the oldest custom-built customs house (heh) in Britain. The cannons were cast in 1789.

Looking back along the quay towards the sea (not that you can see it from here).

Also quayside, straight ahead are part of Exeter’s extensive city walls, which are layered: Roman on the bottom, 17th century on the top, Anglo-Saxon and Norman in between.

My last few photos are from Exeter’s war memorial, built in 1923.

It is surmounted by either Peace or Victory — either way, she’s standing on a slain dragon which presumably represents War.

A POW and a VAD, and behind them, Rougemont Castle (which I wandered into, though I’m not sure I was supposed to).

So that was the sightseeing done. Next was the conference at Exeter University (a very beautiful campus by the way), which formed part of the AHRC project ‘Bombing, states and peoples in Western Europe, 1940-1945’, where Western Europe means Britain, Germany, France and Italy. It’s a very interesting project, and it was a very interesting conference. I got to meet and hear people like Jay Winter, Juliet Gardiner and Richard Overy (the principle investigator for the project) — it’s always nice to put faces to names on the bookshelf!

The experiences of France and Italy under bombing, in particular, are not very well represented in the English language, so I learned a lot from the talks by Elena Cortesi, Lindsey Dodd (one of two PhD students attached to the project), Marta Nezzi, Claudia Baldoli (particularly on the belief that Padre Pio would levitate and intercept RAF bombers!) and Michael Schmiedel. There were a number of papers on the British experience. Dietmar Süss spoke about shelter policy in Britain and Germany, and how they became sites of a struggle for power and authority, while Marc Wiggam (the other project PhD student) discussed the way the blackout helped form and deform communities in the same countries. In Britain these processes were more voluntarist and more freely debated, though the differences in outcomes were perhaps not as great as one might expect. Lara Feigel examined photographic imagery in British and German literary accounts of bombing, Vanessa Chambers explored ways in which Britons coped with bombing (including astrology), and Juliet Gardiner offered a preview of her forthcoming book on the Blitz. Richard Titmuss’ name popped in a number of talks, even on non-British subjects; Problems of Social Policy is clearly still a touchstone for this area of historiography, even more than Angus Calder. Partly that’s because the civilian experience of bombing hasn’t received the attention it deserves. So I hope the promised conference proceedings will appear sooner rather than later! Certainly it was the best — most informative and enjoyable — conference I’ve been to thus far.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

That cadaverous memorial in Exeter Cathedral looks like a transi tomb, very popular in the period immediately after the Black Death.

Exeter’s extensive city walls, which are layered: Roman on the bottom, Jacobite on the top …

Jacobean, shurely!

Argh. In between, actually — Civil War.

Fantastic photos – thanks for sharing them.

The Exeter interiors are stunning: that boss shot is beautiful.

There’s a boss in Exeter cathedral? Is it a spawning site? Was it Richard Overy?

I’m so with it….

The photographs are enormously reminiscent of University of British Columbia’s main library. (Or, rather, the bit in the middle that’s been preserved on account of being historic. The less said of which the better.) I wonder if there’s a chain of inspiration?

Simon:

Are you by any chance the Simon Bradshaw who is thanked in the acknowledgments of The Jennifer Morgue?

Erik:

Groan …

Pingback: Acquisitions | Airminded