The National Archives have released a couple of files (here and here) relating to mustard gas in the Second World War. I’m too cheap to pay to download them from TNA so I’m relying on news reports — luckily this is a blog and not a refereed publication!

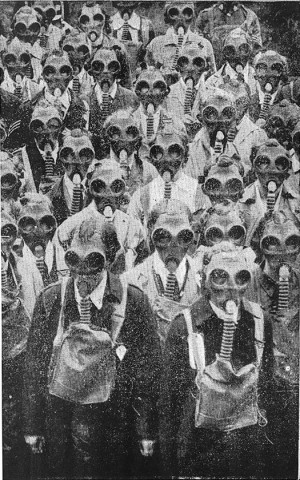

The first is about a series of seminars held in 1943 by the Ministry of Food and the Ministry of Home Security. Their purpose was to inform ‘civilians’ — just who exactly is not clear from the article, but I’m guessing civil defence personnel rather than people pulled off the street — about the effects of mustard gas on food, by way of practical demonstrations. The overall conclusion seems to have been that it was more of a nuisance than anything else, as most things could be decontaminated. (Cheese is particularly resistant, apparently.) This would have been a relief to a number of prewar writers, who predicted that that food supplies were vulnerable to gas attack. Two points. One is that I’m glad that I don’t go to the kind of seminars which involve a risk of mustard gas exposure (22 civilians suffered ‘side-effects’, according The Times, along with 3 officials.) The second is the question of why 1943? Early in that year Allied victory was sealed in North Africa and a German army surrendered at Stalingrad. Perhaps the worry was that with Germany now on the retreat, Hitler might try something desperate to regain the initiative. Or, if the seminars were organised after the devastating raids on Hamburg in July, perhaps it was thought that the Luftwaffe might retaliate. (It did still have this capability, as the Baby Blitz the following year showed — though this was conventional, not chemical.)

The second story is that in May 1944, Britain ‘considered’ (as the headline in The Times has it) using mustard gas against Tokyo. But it would be easy to read too much into this. The report in question — entitled ‘Attack on Tokyo with gas bombs’ — clearly isn’t any sort of operational plan but simply an intellectual exercise designed to provide the top brass with the basis for informed decision-making. (One giveaway is that the author was a boffin, a Professor D. Brunt, who I’d guess was the meteorologist David Brunt.) Still, it’s always a bit confronting to ponder the thinking behind statements like ‘In the densely built areas of Japanese-type buildings, where the streets are narrow, the flow of a gas cloud would be hindered by the narrowness of the streets’. Phosgene could also be used, which would cause large civilian casualties, but the conclusion was that incendiaries would be best, perhaps followed up a few days later with mustard as an area-denial weapon. (Another suggestion was gas first to cause civilians to flee, then incendiaries, though there’s no suggestion in the article that this was in order to minimise casualties.) Again, why 1944? It’s not like Bomber Command was about to start operations against Japan. But the invasion of France was imminent, and with it the prospect of a heavy toll of British military casualties. At this stage of the war manpower was starting to run out. So the eventual need to provide forces for the invasion of Japan must have been daunting for British planners; and for that reason, using technology to substitute for manpower would have been attractive.1 And in fact, later in the year Churchill committed a large contingent of heavy bombers to the war against Japan, Tiger Force — which didn’t go in action because it was trumped by another labour-saving device, the atomic bomb. (Well, that and the Soviet Union’s still relatively ample reserves of manpower.)

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Just as it had been in a similar stage in the First World War: see Eric Ash, Sir Frederick Sykes and the Air Revolution, 1912-1918 (London and Portland: Frank Cass, 1999). [↩]

Brett, you’re missing a key point. Mustard gas, being a vesicant that acts at a cellular level, is the perfect anti-zombie weapon, ideal for getting all those autonomous crawling bits. No doubt the War Office was expecting the A-Bomb to cause a Japanese zombie holocaust. Forward thinking, there.

On another note… the notion of “running out of manpower” is a bit misleading, I think. As long as a nation doesn’t lose more than an annual cohort (over 300,000 in the UK, I think?), it’s good in the medium term. What happened in 1944 was that the casualty replacement pools were misallocated, mainly to the artillery, and the Middle Eastern Base Area couldn’t be dismantled. (IIRC, there’s a discussion buried in _Victory in the West_.)

A better context for this kind of blue-skying _might_ be the air-industrial complex’s reorientation from maximum aircraft production to a “get the new toys out.” Looking at all the specifications and prototype activity in 1944, it would be natural for someone to ask “what will our new turboprop, steel-wool skinned Windsors drop on Tokyo?”

The idea here being, if my speculation is right, to simultaneously prove to the United States (and Australia) that Britain remained a worthy ally through an overwhelming display of cool stuff, and patch up fraying national self-respect after blows such as the Fedden Report and other commentary on comparative productivity.

Fair points! I probably should have said that Britain was starting to run up against the limits of its manpower. It wasn’t scraping the bottom of the barrel (after all, casualties were much less than in WWI), but it couldn’t expand its forces (military or industrial) by much either. After D-Day Britain’s proportion of Allied forces in Europe kept dropping; if there had been massive casualties and a prolonged campaign, and an invasion of Japan was needed …

Judging from this report, it was the Ministry of Supply’s Chemical Board which was interested in this question, so maybe it was about asking what could be done with all this mustard gas that’s lying around.

Not sure about Tokyo, but might the mustard test have something to do with the acquistion of intelligence about the V-weapons programme? Gas makes a kind of sense as a weapon dispensed from a cruise missile.

Yes, that definitely could be. Operation Crossbow started in August 1943 so civil defence planning could certainly have started around then too. Unfortunately I don’t have O’Brien’s volume of the official history to hand, that would probably have some information. There was certainly a worry that the V-weapons would amount to a knock-out blow, given a war-weary populace, and IIRC that would be late 1943 or early 1944.

Pingback: History Carnival 78 | TOCWOC - A Civil War Blog