So. After leaving the Vatican, I headed south.

I walked past these massive walls. I thought at the time they were the Aurelian Walls, built in the 3rd century, which I vaguely knew were somewhere in the direction I was heading. But as far as I can judge, they’re actually much later, built by some pope or other in the Middle Ages.

Crossing back over the Tiber, I found my way to Piazza Navona, which is much bigger and more airy than the one in South Yarra. At one end is the Fontana della Nettuno, or Fountain of Neptune, designed in the 16th century by Giacomo della Porta, whose influence can be seen all over Rome today.

Adjacent to the piazza is the 16th-century church of San Luigi dei Francesi, St Louis of the French. It is in fact the French national church in Rome (designed by della Porta, as it happens). Underneath a statue of St Louis is this curiously dinosaur-like creature, and the legend NVTRISCO ET EXTINGO. It’s actually a salamander, the heraldic device of Francis I of France. Not sure what his connection to the church is, other than perhaps his daughter-in-law Catherine de’ Medici, who apparently helped out in some way.

This was my intended destination: the Pantheon, something I’ve long wanted to see. It’s just astounding that this building has survived intact and in continuous use for so long. For it was built in about 125, and so will reach a lazy 1900 years of age in 2025 or so. Originally it was a temple, more recently a church. (It’s still a church. Some people even get to have weddings there. Just awesome.) It’s built on the site of an earlier temple designed by Agrippa, the friend of Augustus who appears on the Ara Pacis, and his proud claim was reproduced over the portico, as can be seen above: ‘Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, consul for the third time, made it’.

Around 200, the Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote that:

Agrippa finished the construction of the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens.

Here is that vaulted roof (though minus the original metal ceiling, stripped away by the Byzantine emperor Constans II in 663). It’s magnificent.

The hole, the oculus at the apex is 9 metres across and lets in light and fresh air. I had the idea from somewhere that it also relieved the stress on the dome by reducing its weight, but can’t find a source for that. It wouldn’t have had much effect anyway; the indentations would have helped more. The Wikipedia page says that just how the Pantheon has remained intact for so long is a bit of a mystery, that normal Roman concrete would have crumbled long ago. Apparently its builders took especial care to squeeze out air bubbles which would have weakened it.

Right next to the Pantheon is Piazza Minerva (so called because there was a temple of Minerva on this site in Roman times), with this delightful obelisk (Egyptian, 6th century BC) and pedestal, the Pulcino della Minerva. (And behind can be seen a 14th-century Gothic church, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, with a magnificent restored interior. Of which I was completely oblivious at the time. Sigh.)

The obelisk is the smallest in Rome, and the elephant was designed in the mid-17th century by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose name is even more ubiquitous in Rome than della Porta’s. It’s apparently inspired by one of the illustrations in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili (1499), one of the earliest printed books and a wonderfully arcane and allegorical text. I read the 1592 English translation a long time ago, and the recent full translation by Jocelyn Godwin is sitting on my bookshelf waiting for me to finish my PhD …

The Monument to Vittorio Emanuele II, AKA ‘the typewriter’. Inside is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. Behind is the Roman Forum.

On the way back to my hotel, I stopped at the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, a museum near the main railway station and the Baths of Diocletian. I had the place practically to myself — apparently everyone else in Rome could find better things to do on a Saturday evening!

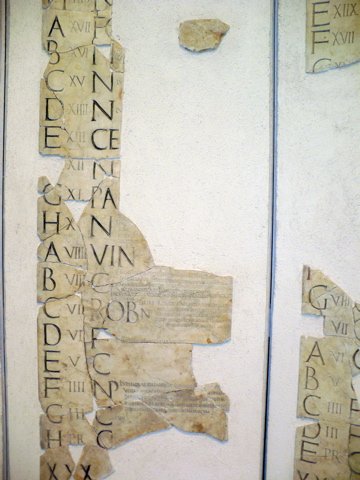

These are part of the Praeneste Fasti, an Augustan-period calendar of various important dates from the forum a town near Rome — religious feasts, the emperor’s birthday and so on. (There were a lot of holidays, but then the Romans hadn’t invented the concept of a ‘week-end’ yet.) It also specified the days on which, for religious reasons, judicial courts and the like could not sit. As you can see, I’ve discovered that the Romans used the same alphabet order as we do! Possibly somebody’s noticed that before now, though.

The chief glory of the Palazzo Massimo is its statuary. For example, Augustus, pontifex maximus, from the last decade BC.

A Greek statue from the fifth century BC, which some Roman plundered or purchased and brought to the Gardens of Sallust. She is one of the children of Niobe, and unfortunately has been hit in the back by an arrow fired by Artemis. On the plus side, it’s done wonders for her bustline.

A rare Hellenistic bronze, dating to the second century BC. Inspired by a statue of Alexander, it may be intended to represent Attalus II, the King of Pergamum, or else a Roman Hellenophile.

He’s pretty clearly a real individual, but this is all that’s left of him now.

Found with the ‘prince’ was this seated boxer, another Greek masterpiece from the 1st century BC. His face shows the scars of his battle.

A Venus Pudica, 1st century BC.

Another beautiful female form …

… ah, no. Well, partly, it is. It’s Hermaphroditus, from the 2nd century.

This looks like a mother and child, at first glance. But as far as I can tell from the Italian caption and Babelfish, it’s actually Tethys (Teti in Italian) and baby Triton (look closely at the legs … they’re not), her grandson. I think.

A Dionysus Sardanapalus, a 2nd century copy of a much older Greek original.

Part of a bronze guard-rail from one of Caligula’s Lake Nemi pleasure barges. The two ships themselves, 70 metres long, were recovered during the Fascist period (when the lake was drained), only to be destroyed by fire in 1944 — whether by the German (intentionally) or American (unintentionally) army is unclear. My impression is that Italy suffered comparatively lightly from the war, in terms of its cultural heritage, but I suppose it couldn’t escape entirely.

The first of three emperors, each in a different style: Septimius Severus (late 2nd century).

His great-nephew, Severus Alexander (earlyish-3rd century).

Gordian III (not long after Severus Alexander). This seems more realistic than the previous two — certainly than Alexander’s, which is very idealistic, but Severus’s looks stylised to me as well.

A late-3rd century sarcophagus, showing a husband and wife (one or both of whom was presumably inside). The way they are reacting to each other seems to show trust and respect.

Part of another sarcophagus, belonging to one Marcus Claudianus, evidently a Christian as it shows a scene from the New Testament. The figures on the previous one were highly individual, very easy to imagine meeting them in real life. Here they’re far more stylised, with angular faces and pointy noses, which I found less to my taste. I did very much like this detail of a child trying to catch a chicken, though.

Second century floor mosaics, showing chariot racers from the different circus factions, along with (I guess) their favourite horses.

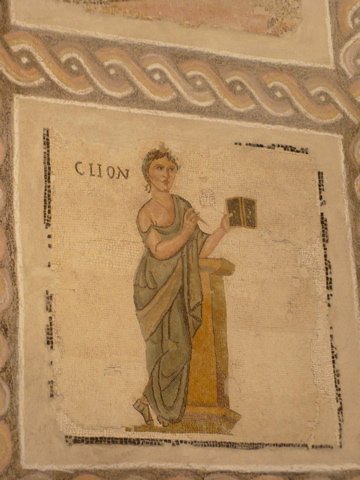

I could hardly resist Clio, muse of history! This mosaic and the preceding ones are from the Villa Baccano, which seems to have belonged to the Severans.

One of the last things I saw before closing time was the wonderful room brought from the villa of Livia, wife of Augustus. The walls are decorated with trompe l’oeil frescos of a garden, very softly lit and absolutely no photography allowed. So instead I’ll end with this view of the Piazza della Repubblica at dusk, which ain’t bad but is not nearly as nice.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Can’t agree with Wikipedia on Roman concrete, at least not as a universal principle. When in York I took part in several archaeological digs. On one we were excavating a section of the Roman wall, just off Lendal. The Victorians had built a terrace of shops over the top, with concrete foundations. While removing the “modern” accretions, one was immediately, sometimes quite painfully, aware of reaching the Roman substrate as the pick bounced back.

You’re probably right — I was a bit surprised by the mystery-mongering tone of the Wikipedia article. I did forget to mention, though, that it does point out that the Pantheon dome is unreinforced, which does make it more impressive. Google throws up this, which only suggests that there ‘could’ have been a catastrophic failure, not that there ‘should’ have been one.

Pingback: Airminded · Rome 2a

OK, it happens that OUR alphabet is actually called the Latin (or Roman) alphabet! Not only we use the same order of letters they did, we actually borrowed the letters themselves (and their order) from them! (they in turn had borrowed it from the Etruscans, Greeks, etc)