One of the things I love about the official history of the RFC and RAF in the First World War is all the maps — multi-panel fold-out jobs showing where bombs fell in London during the Gotha raids, or the Allied front in Macedonia. That’s not to mention the accompanying slip-cases stuffed full of more maps of the paths taken by Zeppelin raiders and the like. I could pore over these for hours …

Here are a couple of the maps (or parts thereof) showing two different kinds of barrages associated with the air defence of Britain.

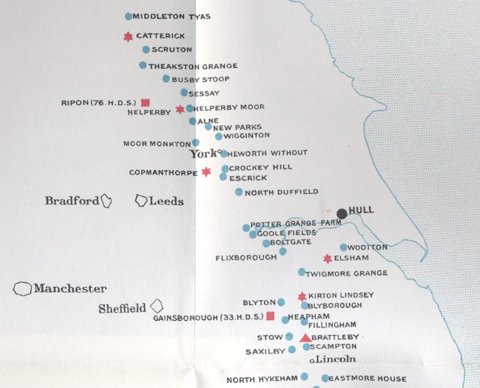

The first one is entitled ‘Aeroplane barrage line. December, 1916.’ It’s too big to show effectively, so I’ve just reproduced a portion showing the coast of Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. The red squares show home defence squadron HQs: 33 Squadron at Gainsborough and 76 Squadron at Ripon. The red triangles are flight stations, the red stars flight stations with searchlights, the blue circles are searchlight stations under squadron control (‘aeroplane lights’) and the black circles are warning control centres (Hull).

As I’ve discussed before, artillery barrages weren’t the only kinds of barrages. Originally they seem to have just been barriers or walls of some kind (barrage originally referred to a dam). Here the barrage is composed of aeroplanes and searchlights, a wall erected to hopefully bar Zeppelins coming in over the North Sea from reaching the industrial cities behind the line. And it does look like a barrier: on the full map it stretches from Suttons Farm (later renamed Hornchurch) near London all the way up to Innerwick, east of Edinburgh (with extensions in Norfolk and Kent). But it’s not a physical barrage, for the most part — it’s aerodromes and searchlights. Previously, home defence squadrons had been placed close to target areas, because of doubts about night navigation and interception. Experience had shown that these problems weren’t as great as previously thought:

Now that it was clear the aeroplane patrols could be extended, it was suggested that the Flights situated near Birmingham, Sheffield and Leeds should be moved farther east as a step towards the ultimate establishment of a barrage-line of aeroplanes and searchlights parallel with the east coast of England.1

This system worked very well against Zeppelins (as one indication, note the steep drop in casualties due to airship raids from 1917 on). But not so well against Gothas.

This map shows the anti-aircraft gun barrage in and around London in October (or so) 1917, which were there to defend against night raiders — aeroplanes, now, much more than airships. Not that the guns were particularly effective, but they were heavily used. So heavily used, in fact, that there was a serious concern that London would soon run out of AA guns through wear and tear (each gun lasted for a maximum of 1500 rounds, and 14000 rounds total were fired on 30 September alone).2

But the barrages on this map, the red lines, do not show the location of the guns. They show lines in the sky along which a number of guns could be brought to bear (which explains why they are mostly made of arcs). So, again, the barrages are barriers. As the note in the top left corner explains:

Note. This type of barrage, usually known as ‘Linear’, allotted fuzes, bearings, and quadrant elevations so that fire could be directed at a particular altitude over a definite area. The barrages varied in length and form according to the situation and number of the guns which could be brought to bear. The height of the barrage could be varied at will. Orders for this form of barrage were given only occasionally, usually to ‘screen’ certain important objectives or to catch raiding aeroplanes whose courses were doubtful.

So, if I understand this correctly, if Gothas were seen approaching Woolwich Arsenal from the south-east, several guns would receive the order ‘Ace of Spades’ and would then swing to pre-determined settings to set up a barrier of fire for the raiders to fly into. If they flew on instead towards the Isle of Dogs, the order ‘Robin Hood’ would then be sent, and a new barrier would be set up, probably drawing on some of the same guns but with others joining in too.

There were also guns arrayed along the grid squares, the original scheme to which the linear barrages were a supplement. There is a hint that the linear barrages were meant to be a more efficient, more selective alternative, to help with the wear and tear problem.

As an aside, I wonder who came up with the barrage names? Some of them could be standard military issue: Kingfisher, Mercury, Union Jack. But what about Noisy Norah, Charley’s Aunt or Dandy Dick? (The last two, at least, seem to be the names of popular farces.) Did the gun crews have a say in it, or were they named on the whim of some bored junior officer?

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- H. A. Jones, The War in the Air: Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, volume 3 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1931), 166. The map faces 170. [↩]

- H. A. Jones, The War in the Air: Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, volume 5 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1935), 85-6. The map faces 89. [↩]

It wasn’t the defences that stopped the Zeppelins so much as the fact that they were dirigibles and, speaking as a technical historian rather than a nerd, dirigibles are just not a very good idea.

Well, although quite a few were lost to non-military causes, a sizeable fraction of them (ISTR the majority lost over the UK) succumbed to the well-know design flaw of the hydrogen-filled airship: inability to cope with incendiary bullets.

Nice one.

The Barrage system brought in against the V-1s in W.W.II worked on a viable ‘bands of defence’ system. Given the nature of the attacks there, it made more sense than the politically popular ‘walls of lead’ type defences which generally failed to shoot down many (any?) raiders in either war.

I suspect these maps are in part the result of self-comforting propaganda and a different availability of alternative images in the era.

The main thing to remember was the raids forced a lot of units that should have been thumping the Hun getting brought to the UK to save politician’s seats. It was a German victory, but just not a big enough one for them.

A recent History Today magazine has an interesting article on maps in war and propaganda.

Erik:

Yes, the ultimate cause for the failure of the Zeppelins was that they were pretty useless, but the proximate cause was, in part, because the defenders got their act together and started shooting them down! None at all were shot down by fighters before September 1916, and then six were shot down before the end of the year, five by fighters and one by AA. As Chris says, incendiaries made a huge difference. More so than the barrage line as such, but it seems to have been well-placed for interception.

JDK:

Yes, it’s very true that maps can be political in nature, but I doubt that these ones are meant to be reassuring, because one of the conclusions of the official history was that ‘the only defence in the air likely be effective in the long run is an offensive more powerfully sustained than that conducted by an enemy’ (vol. 5, 149). Jones (and Raleigh, the original official historian) were pretty Trenchardian.

It is frequently forgotten that what goes up must come down. AAA often does more damage than the attackers, and with little chance of success, but civilians get upset when they aren’t present.

On the matter of Zeppelins, in 1914 the dirigibles had a considerable performance advantage, especially if the defender had to climb 10-15,000 feet or more (near or above the ceilings of many of the aircraft available) to intercept so it was by no means a no-brainer that the Zeppelins would fail.

Despite modern conceptions of the flamibility of Zeppelins, they were surprisingly difficult to shoot down even with incendiary ammunition and I recall reading an account of an entire drum of ammunition being fired into one to no effect. An entire arsenal of weapons was tried, and discarded. Explosive darts, rockets, bombs and various types of special guns failed.

They would only ignite when oxygen was mixed with the hydrogen. It was discovered that the best tactic was to shoot across the edge of the curve rather than directly into the side as that caused more venting, and the incendiaries spent more time where the air and hydrogen could mix, rather than deep inside the ballon. Hydrogen is actually less flamable than gasoline.

Probably the biggest factor in their demise was that their speed and altitude advantages disappeared, leaving them open for repeated attacks until someone could get that fatal shot.

As aircraft speeds, climb rates and ceilings further improved, the odds went spectacularly in the favour of the attacker. Very much the same story for any bomber coming to the end of its service life in wartime, and not all that different that the fate suffered by many of the Japanese aircraft of WW2. I was sure that more had been shot down than 6 – that sounds way too low (perhaps that is only the ones shot down over the UK?)

Perhaps most telling is that hydrogen filled observation ballons continued to be used by both sides throughout the war.

Cheers,

Mike

Thanks for your comment, Mike, all good points. Yes, it was just the ones shot down over the UK, and it’s just for 1917. (There were one or two more shot down in 1918, I think.)

Pingback: Military History and Warfare: 19th Military History Blog Carnival – Military History and Warfare