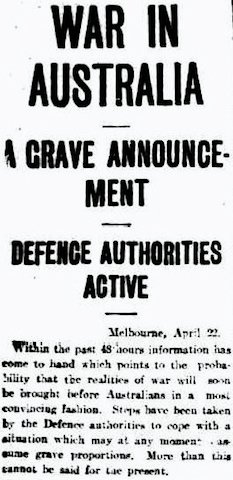

On 23 April 1918, this brief article, filed from Melbourne, was the lead story in a number of Australian newspapers:

Within the past 48 hours information has come to hand which points to the probability that the realities of war will soon be brought before Australians in a most convincing fashion. Steps have been taken by the Defence authorities to cope with a situation which may at any moment assume grave proportions. More than this cannot be said for the present.1

That’s not much, but it seems to have created quite a stir: according to the Perth Sunday Times, ‘Australia was startled out of its somnolence’.2 The Melbourne Argus reported that ‘Uneasiness was caused in Melbourne and in other centres’ by the previous day’s story, giving rise to ‘most exaggerated rumours in the city’.3 A report in the New Zealand press also dated 24 April (but not published for another week) noted that the public in Sydney ‘fairly seethed in excitement’ at this news when it was published in the Daily Telegraph.4 Why? The report explains that

At the moment, Australia is suffering an attack of nerves in the matter of raiders, and any old story is accepted and sent wildly circulating. Certain definite signs of uneasiness in official circles, and certain things which cannot be hidden from the people have given colour to the wildest rumours. There is “something doing” — but nothing to justify the excited stories of an imminent enemy attack on Australia which are now current.

So it seems that rumour had already prepared Australians to think that German naval raiders were lurking off the coast, and when they were told that ‘the realities of war’ might soon be present to them ‘in a most convincing fashion’, they believed that this meant an ‘imminent enemy attack on Australia’. Or, as the Sunday Times put it, they had ‘Visions of a German squadron breaking the British blockade and landing an expeditionary force on the Commonwealth coast’.2

The reason given by the New Zealand journalist for this ‘attack of nerves’ is the mystery aeroplane sightings: those at Toora and Casterton are mentioned, and that Australian aeroplanes could not be shown to be responsible. Then there were ‘reports of aeroplanes and strange lights on or near the coast between Melbourne or Sydney’ — which I haven’t come across yet — ‘and a whole crop of rumours based on certain events of which the censorship forbids mention’. More government cover-ups! But the New Zealander perhaps slips one past the censor with this gem used to introduce the story:

A couple of days ago a man, selling the noon editions of the evening papers, stood in Castlereagh-street [Sydney] bawling “Raiders off the Queensland Coast.” The rush for papers nearly carried him off his feet; and when the purchasers of his wares found not a line about a raider anywhere, they just grinned and, in the strange Australian way, seemed more inclined to commend his enterprise than damn his dishonesty.

I have no idea if the newspaper-seller was passing on a rumour he’d heard or just made it up on the spot, but this episode permits us a brief insight into the way these stories might have spread.

So what was the story behind this ill-advised warning? It seems that, thanks to the mystery aeroplane sightings, the government did in fact take seriously the possibility that German commerce raiders were operating off the Australian coast at this time. I haven’t found a good account of this episode (possibly because of my unfamiliarity with Australian historiography) but we can reconstruct much of it from both primary and secondary sources.

First of all, there’s a statement from the Minister for Defence, made the same day as that alarming press report:

Referring yesterday to the rumours, which were in circulation, the Minister for Defence (Senator George Pearce) stated that there was nothing that need alarm the public, but it had been thought advisable to take certain action of a precautionary nature to guard against any interference with our shipping.3

Why was it ‘thought advisable’? Well, confirming the New Zealander’s narrative, Pearce went on to speak ‘in reference to the various reports of aeroplanes having been seen in certain places in Victoria’. He didn’t comment directly on their reality (or lack thereof), but for the benefit of planespotters explained how to distinguish friend from foe:

All British and Australian aeroplanes are visibly marked with three concentric circles of colour — red, white, and blue.

German planes are marked with large black crosses, in the shape of the “Iron Cross.”5

He then pointed out that ‘Any German or other enemy subject using an unmarked plane, or one with British markings, is subject to the penalty of a spy’. Once again, this opens up the possibility of a threat not just from a German warship, but from German agents too. A commentator in the Evening News remarked that

It is not impossible for enemy sympathisers in Australia to manufacture an aeroplane or two; indeed, there are certain lonely districts in Victoria where the thing might be done. Not impossible, but not probable.2

Any sightings should be reported ‘at once to the nearest military officer or the police, and that not only should markings be described, but date and time, direction from and to, sound, and if possible sketch of outline’. So the mystery aeroplanes were clearly a matter of concern, and the reason for the precautions.

And what were the nature of those precautions? They should not be exaggerated: as of 23 April, one shipping company was advised by the Royal Australian Navy that ‘it need have no fear for its vessels […] Enquiries of other shipping firms showed that not one single sailing had been cancelled’.6 So Pearce’s precautionary measures did not extend to the interruption of commerce.

But what did happen was a not-insubstantial mobilisation of what few military and naval forces Australia had left for home defence. Coastal defence batteries which had been stood down were ‘remobilised and the forts again manned for a month’ in April 1918.7 German men interned at Trial Bay on the NSW coast were moved inland to Holsworthy at about this time too, because of the possibility of a rescue by a German raider.8

Obviously the greatest burden of defence against raiders would fall on the Navy. The official history of the Navy in the war has this to say:

In 1918 the news of the Wolf’s doings of the year before, the possibility that Germany might get a successor to her through the blockade, and the widespread rumours concerning enemy aeroplanes — too numerous to be neglected, however unlikely — made it advisable to establish a more thorough system of patrols. The lack of warships was made up for, as far as possible, by commissioning a number of small craft, which could at any rate give warning of an enemy’s approach, and by resuscitating the older warships, however inefficient.9

In the areas near where the mystery aeroplanes were spotted, the patrol vessels were Coogee (a converted ferry), Countess of Hopetoun and Protector (the latter two survivors from colonial days), with others covering the coast right round from Western Australia to the Torres Strait.

And what of the Australian Flying Corps? As noted in my previous post, it had just one bomber available in Australia, an F.E.2b. And according to James Kightly, it was based at Alberton in Victoria from 20 April, and later moved to Yarram. From these bases it conducted reconnaissance sweeps off the Gippsland coast looking for German commerce raiders until at least May. An unarmed Maurice Farman Shorthorn assisted Protector in her patrols from Bega, on the south-eastern coast of NSW. James also notes that ‘In March-April 1918, there were numerous “sightings” of lights in the sky and on the grounds and mysterious aeroplanes — leading to the conclusion that up to four raiders could be operating off the coast of Australia’ — so in fact he beat me to these mystery aircraft!10

And that’s pretty much where the story ends, at far as I can tell. There were very few more mystery aeroplane reports. On 29 April, an aeroplane flying over Sydney ’caused many of the people who saw it to become unnecessarily alarmed’: it was in fact a new military aeroplane being test-flown by Lieutenant Stutt.11 And nearly a month later, the Grey River Argus in New Zealand claimed that ‘A report was circulated in town last evening that an aeroplane had been seen over the sea near the hospital last evening’ (yes, that’s two ‘last evening’s, so either 28 or 29 May).12 No suggestion that it was mysterious in any way, but then why report it?

That seems an unsatisfactory place to leave it. Perhaps I’ll leave the last word to our Kiwi friend, who (in a different version of the article quoted above) places the raider scare in the context of the failure of the government to win public approval for conscription, the continuing German offensive in France and Australia’s defencelessness. Scares have their uses, after all…

But military circles are likely to be disappointed. They did not expect compulsion for service abroad, but they did think that men would be compelled to provide a couple of divisions at least for home defence. The anti-compulsionists won all along the line at the recruiting conference last week, and now only volunteers are called for, to build up a small home army. Certain possibilities make that home army quite a necessity but apparently it is to be built up with all the muddling and expense that marked the creation of the armies now abroad.13

PS Okay, here’s a different last word, a memory of a 1909 scareship sighting in Western Australia: Sunday Times (Perth), 28 April 1918, 6!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Advertiser (Adelaide), 23 April 1918, 7; reprinted in Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), 23 April 1918, 2. A different version, originating in the Age (Melbourne) adds the sentence ‘The uneasiness of the Defence authorities has been intensified by certain evidence which has come before them since Saturday morning’ [20 April]: Sunday Times (Perth), 28 April 1918, 13. [↩]

- Sunday Times (Perth), 28 April 1918, 13. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Argus (Melbourne), 24 April 1918, 9. [↩] [↩]

- Evening News (Wellington), 1 May 1918, 11; reprinted in Poverty Bay Herald, 4 May 1918, 7. [↩]

- Also printed in Sydney Morning Herald, 24 April 1918, 11. [↩]

- Evening News (Wellington), 1 May 1918, 11. [↩]

- Ernest Scott, Australia During the War (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1941), 7th edition, 198. Scott doesn’t mention the mystery aeroplanes, saying that the remobilisation was due to ‘the realisation that the German raider Wolf, as well as the Seeadler, had in the previous year been operating in neighbouring waters’, but that realisation in and off itself would not appear to justify a belief in a current threat. [↩]

- Ibid., 122-3. [↩]

- Arthur W. Jose, The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1941), 9th edition, 373. [↩]

- James Kightly, ‘Australia’s first domestic battleplane’, Flightpath, 20:4 (2009), 54. See also this 1938 article posted at Wings Over New Zealand, which refers to sightings of the Wolf‘s seaplane, but either those took place in 1917 or they weren’t actually of the Wölfchen. [↩]

- Sydney Morning Herald, 30 April 1918, 7. [↩]

- Grey River Argus, 30 May 1918, 2. [↩]

- Poverty Bay Herald, 4 May 1918, 7. [↩]

Those phantom raiders are elusive, aren’t they?

I’d just like to add, after Brett’s very kind citing of an article I wrote a couple of years ago, that a great deal of original research in that article had been done some time previously by several other people. I was just requested to reproduce in summary the fascinating but generally forgotten story of the FEE. As per the end of my article:

The article is based, with thanks and acknowledgement, on research and photographs provided by Jack Gillies, taken by his father ‘Digger’ Gillies, and via Maurice Austin, including text and notes from ‘Man and Aerial Machines No.23’, July-August 1991, and original research by Trevor Boughton and John Hopton.

The research credit in this case is entirely theirs!

Ah, but as far as scholarship is concerned, if I can’t cite it it may as well not exist :) That said I should look up Man and Aerial Machines…

There is a document in the National Archives of Australia B197, 2021/1/126 (item barcode 417906) titled “Possible enemy Raider [Air Reconnaissance]” dated 1918 from the Secret and Confidential correspondence files.

Not yet digitised for online viewing. I wonder if it has anything to do with these newspaper reports.

Thanks, Bob! I’ve had a look in RecordSearch myself now and found nearly 20 other files which look promising. And as luck would have it, most of them are in Melbourne, so I’ll definitely have a look at them.

Pingback: Airminded · Dreaming war, seeing aeroplanes — II

Pingback: Airminded · Smithy and the mystery aeroplane

Pingback: Airminded · Fear, uncertainty, doubt — IV

Pingback: Tuesday, 23 April 1918 – Airminded