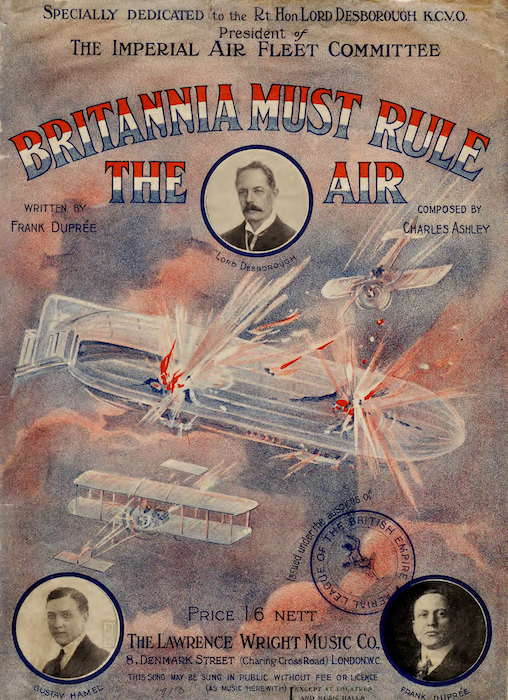

This stirring scene is the cover for the sheet music for a song published in 1913, Britannia Must Rule the Air, written by Frank Duprée and composed by Charles Ashley. It shows a reasonable (if stubby) approximation of a Zeppelin in the process of being destroyed by gunfire from two aeroplanes, a Farman-type biplane and a monoplane.

The lyrics are a little more subtle:

When wooden walls and straining sails bore Britain’s flag afar,

The Nation prospered well in peace and feared no foe in war,

For Britain’s might was ev’rywhere and ruled the endless waves,

Proclaiming to the world at large ‘we never shall be slaves.’And when the ironclad replaced the ships that caught the breeze

Britannia still retained her throne up on the charted seas,

For frowning fleets and giant guns outnumbered two to one

The navies of all other lands beneath the sov’reign sun.And now that ev’ry cloud conceals a lurking bird of prey,

Which threatens our supremacy in peace and war today,

Britainnia must be equal to the peril and prepare

To hold our Empire sacred from these dreadnaughts of the air.CHORUS

Britannia must rule the air

As still she rules the sea,

To guard this realm beyond compare

And keep her people free.

Britannia, Britannia must like the eagle be;

Britannia, Britannia must rule both air and sea!

Britannia, Britannia must rule both air and sea.1

The message is clear enough: just as Britain’s naval superiority has kept it safe from the Napoleonic Wars through the ironclad era to now, so must it have a superiory aerial superiority to safeguard its freedom in the new century. This was exactly the comparison and the message of the Navy League in response to German aerial superiority, as supposedly revealed by the phantom airships supposedly seen flying all over Britain.2

As well as being a (insert opinion here) lyricist, Duprée was a journalist for the Evening Standard, and in April he had flown as a passenger on the first return flight across the Channel; his pilot was one of the best-known British pilots of the day, Gustav Hamel, whose image is pasted on the cover alongside Duprée’s. The purpose of their flight was, like ‘Britain Must Rule the Air’, to highlight Britain’s aerial vulnerability.

As well as being a lyricist and a journalist, Duprée was also a playwright, because in June his play War in the Air premiered at the London Palladium (which I’ve discussed before). The purpose of his play was, once more, to highlight Britain’s aerial vulnerability.

This all seems to have been part of a coordinated propaganda campaign. War in the Air was sponsored by the Aerial League of the British Empire, which of course alongside the Navy League and the Conservative press had been part of the agitation for a million pounds to be spent on military aviation. ‘Britannia Must Rule the Air’, too, was ‘Issued under the auspices of’ the Aerial League (the above logo, which I haven’t seen before, is enlarged from the cover). I don’t know when exactly the sheet music was published, but in July the Portsmouth Evening News ran an article under the headline ‘Britannia Must Rule the Air’:

With this its motto, the Aerial league of the British Empire is out to conquer public opinion and make our country safe against the new menace. Under inspiring auspices, it began its campaign in the towns of South coast on Friday night [18 July 1913] with a striking lecture and meeting on the South Parade Pier.3

And, as well as being a lyricist, a journalist and a playwright, it turns out that Duprée was a public speaker:

Explaining a number of moving pictures and slides relating to aircraft which were thrown on a screen, [Duprée] declared that the next war we should have to face would be a war in the air, with sneaking vultures pouring down a rain of fire upon helpless creatures who would not have ghost of chance unless they were able to meet airships with airships. A monoplane costing at the outside £1,200 could carry 10lb shells of high explosive force, which would incalculable damage. Germany had 700 such aeroplanes, all equipped for war, and with pilot and trained passenger for each: whereas we possessed only 14 that could safely relied upon for defensive purposes. Moreover, Germany 34 possessed Zeppelins, and each of them could carry a magazine for great shells, the explosion of two of which, owing to the direct damage done and the terrible force of the concussion, would suffice to wreck half London. In the matter of dirigibles, possessed just three ‘babies.’ Germany had her plan ready, so that when war was declared every airship would go to a designated spot, and all would act together. England was face to face with the greatest crisis in her history. We must have the supremacy of the air as well as of the sea, and the people must demonstrate their will now, or it might be too late.4

The auspices may have been inspiring, but the song and the slogan sank without a trace; I cannot find the phrase ‘Britannia must rule the air’ in the British Newspaper Archive after this. It must have had a somewhat broader impact, though, for, somewhat incredibly, there’s a British Pathé newsreel of what may be something to do with the Portsmouth meeting, though it does look rather staged. I can’t recommend watching it, unless you want to waste two full minutes of your life watching inaudible men sitting around a table, but the ‘Britannia must rule the air’ motto can be seen on the wall behind them:

The Aerial League executive committee minutes don’t shed much light on what went wrong, except that a meeting several days later confirmed the actions of the chairman, General H. T. Arbuthnot, ‘in cancelling the agreement between the Aerial League and Messrs Scott & Dupree’.5 The Aerial League did attempt to continue its south coast tour, in unison with the Women’s Patriotic Aerial League, but without, apparently, much more success.6

Although this isn’t mentioned at all in the press reports, there was also evidently some connection with the Imperial Air Fleet Committee, as the song is specially dedicated to its president, ‘the Rt Hon Lord Desborough KCVO’ (father of Julian Grenfell, incidentally), who can be seen in the chair at the beginning and the end of the newsreel. At exactly this time, the Imperial Air Fleet Committee was raising funds for aircraft to donate to the Dominions. The first was actually the Blériot flown by Hamel and Duprée across the Channel, which was named Britannia and handed over to New Zealand in September 1913.7 So if Britannia did not yet rule the air, at least Britannia’s children were making some progress.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Frank Duprée and Charles Ashley, Britannia Must Rule the Air (London: Laurence Wright Music Co., 1913). [↩]

- Brett Holman, ‘The phantom airship panic of 1913: imagining aerial warfare in Britain before the Great War’, Journal of British Studies 55, no. 1 (2016): 99–119 (free). [↩]

- Evening News (Portsmouth), 19 July 1913, 6. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Aerial League of the British Empire executive committee minutes, 23 July 1913. I’m not sure who Scott was. The same minutes also record a vote of thanks in relation to the Portsmouth meeting to Hercules Scott, a recently-elected member of the executive, though not Duprée; I don’t think this would be the same person. [↩]

- E.g. Bournemouth Graphic, 15 August 1913, 14. [↩]

- Michael Paris, Winged Warfare: The Literature and Theory of Aerial Warfare in Britain, 1859–1917 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992), 98. [↩]