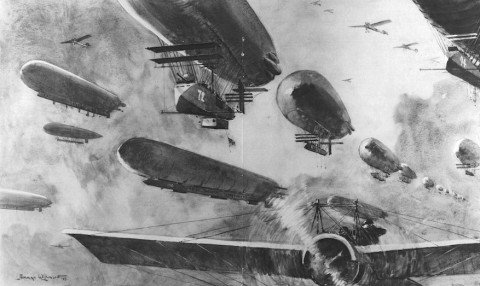

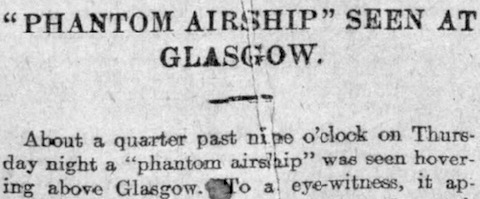

The Illustrated London News is not really a campaigning newspaper, but it has followed up last week’s striking graphical depictions of the airship menace with this fantastic double-page drawing by Norman Wilkinson, RI, of a German aerial fleet on its way to bomb Britain (pp. IV-V; above). The title asks

WILL IT EVER BE SO IN THE EASTERN SKY OVER ENGLAND? THE COMING OF THE BATTLE-DIRIGIBLES AND WAR-PLANES

The caption explains that the Aerial Navigation Act ‘forbidding the passage of unauthorised air-craft over certain areas’ was ‘deemed advisable in view of the numerous reports current of late of strange air-ships manoeuvring by night over this country’.

The fact gives particular interest to this drawing, which represents the eastern sky of England as we may one day see it if the fears of some are realised. It shows an army of invading air-craft. In the middle is the main battle-squadron of air-ships with appliances for bomb-dropping; in the foreground and in the background are high-speed aeroplanes acting as the fleet scouts. Unless met by a stronger opposing force, such an army of air-craft could clear the way for the water-borne fleet of its country and so facilitate the landing of large bodies of troops. It may be remarked that from a height of a mile on a clear day a vision of ninety miles can be obtained.

The text in fact nowhere identifies where these invaders have come from, but airship no. 72 is flying what looks very much like a German war ensign.

The mystery airships have hitherto largely been ignored by the weekly press, apart from the aeronautical trade journals and the ILN. But this week — Saturday being the day on which most weeklies are published — is different. The Spectator, the Economist, and the Saturday Review all discuss the matter today, as indeed do the ILN, as noted above, and Flight, which says that ‘It seems to be more or less accepted that a German airship visited our shores in October‘, hence the Aerial Navigation Act (p. 238). On the other hand,

Since the Sheerness affair, people have been sighting airships all over the country, and always by night. We, ourselves, do not take the matter at all seriously, and, not to put too fine a point upon it, we incline very much to the belief that these phantom airships are quite imaginary craft.

But the important point, says Flight, is that ‘if Germany wants to send airships to cruise over these islands there is no one to say her nay’, since Britain is so far behind in the air. ‘One of these days we may wake up.’ This is essentially the consensus among conservative publications now. The Spectator, for example, quite strongly condemns the scareships while simultaneously embracing the scare. Thus on the one hand (p. 343):

The only reason we mention the subject is to deplore the atmosphere of silly panic created by the rumours. To admit the need for protecting ourselves is one thing; to give way to a fit of nerves and use panic-stricken language is another. It really is despicable. Our countrymen are at their worst when they see an airship in every light or star, and a spy in every restaurant.

But on the other:

Our business is to build a fleet of dirigibles adequate for our protection as quickly as possible. Dirigibles can only be met by dirigibles. Aeroplanes are almost useless by night, and a dirigible is a very poor target for any gun yet invented that fires from the ground.

Saturday Review is also doubtful about the phantom airship scare (p. 254):

The untrained eye, like the untrained intelligence, is notoriously not a thing to trust in implicitly for nice observations. Moreover many people busy with other affairs will often, in a perfectly innocent way, confuse something they have seen in print with something they believe they have seen in fact. Thus, after reading a great deal about, say, a mysterious or menacing aeroplane, there are plenty of people who believe that at such and such an hour, on such and such a day, they heard its whir overhead.

But thinks that some good may come of it:

Yet the scare will be of some service if it concentrates public opinion on the whole question of airships and aeroplanes. Whilst Germany has taken great pains over her airships, and France has done quite wonderful things with her large fleet of aeroplanes, England has officially done next to nothing.

By contrast, the Economist is not conservative but liberal, even radical, and is not at all moved by the demands that Britain simply must embark on a large airship construction programme ‘beyond an experimental expenditure’: ‘We do not regard airships with any great anxiety’ (p. 506). Indeed, it comes close to accusing conservative newspapers and armaments manufacturers of conspiring to deceive the public with an ‘airship hoax’:

it may be significant that the newspapers, just before the issue of the Army and Navy Estimates, should be calling attention to the fact that an airship is supposed to have been seen hovering over various towns in England […] It is just possible, we think, that the companies interested in airship construction may have arranged such a cruise for the purpose of working up a newspaper scare with a view to increasing our public expenditure upon airships.

Otherwise, ‘the hunter after truth will have to choose between Venus, fire-balloons, and whisky’.

Venus is said by the Western Times to have momentarily fooled the West Hartlepool Finance Committee, who ‘suspended their meeting to see a mysterious airship’, but ‘came to the conclusion that the object at which they were looking was the planet Venus’ (p. 4). But fire balloons seem to have become the theory du jour: as a correspondent to the Liverpool Echo suggests, it seems probably that ‘the ancient art of practical joking is being revived on a large scale’ (p. 6). The Western Times has a useful explanation of just what a fire balloon can do (p. 4):

Well-constructed fire-balloons, such as can be purchased for a few shillings from any of the firms dealing in pyrotechnical goods, are capable of travelling long distances in favourable wind; in fact, their range is practically only limited by the quantity of methylated spirit, the heat from which gives it the power of ascension, which they can carry.

Kites are another possibility: the Daily Mirror reports that the ‘Strange night lights seen in the sky over Liverpool are now stated to have been shown from a kite belonging to Mr. James Roberts, of West Derby, who is a well-known kite flyer’ (p. 4). But even here fire balloons seem to be at least part of the explanation: one was found yesterday In this case, the hoaxer may even have been caught in the act by ‘a lady, a teacher at the Wallasey School of Art’, though the evidence is only anecdotal (Liverpool Echo, p. 6):

One night in the middle of this week, while walking in New Brighton, she saw a young man lighting up a fire-balloon. The spectacle interested her, and so she stayed to watch him until he had finished the business.

He released the balloon, which soared away in the direction of New Brighton Tower; and as she walked away he remarked to her gleefully, ‘You’ll hear everybody saying to-morrow that they’ve seen an airship passing over Wallasey.’ And sure enough, when she entered the Art School the following morning, a strange light which had been observed in the skies the night before was the topic of general conversation.

A fire balloon was in fact found at nearby Seacombe, according the Manchester Guardian, and it is ‘believed to yield the solution of the “airship” mystery at New Brighton and Liverpool on Thursday night [27 February 1913], when several people declared they saw a swiftly moving bright light coming from the Irish Sea and passing over the batteries’ (p. 9).

Some ideas die hard: according to the Western Times, ‘It has been suggested that fire-balloons have been sent up by Germans living in various parts, with the view of hoaxing the English people’ (p. 4). Those making such suggestions probably wouldn’t accept at face value the word of ‘Dr. Erckener [sic], the manager of the Zeppelin Company‘, who has sent the following telegraph to the Daily Express‘s Berlin correspondent (p. 1):

I can assure you no Zeppelin airship ever went to England, not even anywhere near British shores.

We once intended sending the airship Schwaben to visit London in the summer of 1911. We communicated with the British Aero Club in order that the British public should be informed.

Before the Aero Club replied there came the Morocco trouble about Agadir, and the flight of the Schwaben was postponed.

Any sensible German airman would consider it most unwise to take an airship over to England, especially under present circumstances.

Still less would they accept the suspiciously similar statement from the German Admiralty, as relayed through the Berlin correspondent of the Daily News and Leader (and reported here in the Irish Times, p. 7):

The Admiralty today authorises me to say that not only has no German airship been over England, but also that no vessel has been near enough to make a casual visit even tempting. There are only four German vessels which could make the trip — ‘Lz I’ [?] (naval), the new military Zeppelin, the Hansa, and the Victoria [sic] Luise. These could not have made such a trip unobserved.

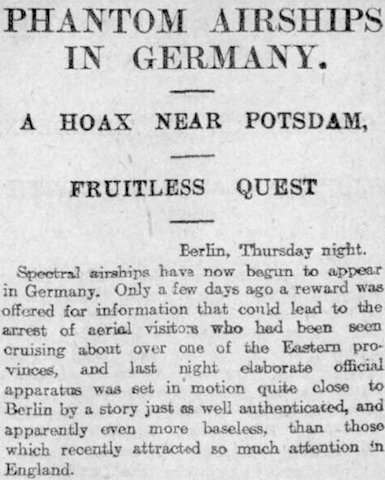

And they definitely wouldn’t like Kölnische Zeitung calling ‘the airship scare “The New English Sickness,” for which the country’s own common sense is the only physician’ (Manchester Courier, p. 8). The Kölnische Zeitung, incidentally, thinks like the Economist, finding ‘the most likely explanation of the matter in the desire of the Conservative Press to work up popular sentiment in favour of great demands for armaments, which presumably would be among the first undertakings of a Conservative Cabinet in the case of change of Government’.

Mystery airships are still being seen in many parts of the country: as the Manchester Guardian says, ‘“EVERYBODY’S DOING IT”‘ (p. 9). In setting out the week’s record of reports, it says that ‘no conclusion can be drawn except that nearly a score of airships are flying over England by night or that not one is doing so, for there is no reason why the evidence for some appearance should be accepted and that for others rejected’. Most of the entries on the list have of course been reported previously, but a few are new. The one from Kirkcaldy, Fife, on Thursday night [27 February 1913] and yesterday morning’ is covered by the Dundee Courier (p. 5). It was only seen by ‘those whose occupation kept them out of doors in the “wee sma’ oors”‘, for example ‘One of the residenters in what is probably the highest parts of the west end, who attends to the feeding of animals [who] shortly after two o’clock in the morning was struck by the unusually bright light overhead’:

It was a starry night, but this light was considerably larger than any of the stars, and the impression that the gentleman formed was that it appeared to be moving very slowly, first towards the sea coast and then in the direction of the Forth Bridge.

‘Did it strike you as being any kind of aircraft?’ was the query put.

‘Well, now that you put the question, it did resemble pictures I have seen showing the possibilities of these machines in use during the darkness.

‘I am certain,’ he added, ‘that it was not a star, for the light, though very high in the heavens, appeared to be focussed upon something, and reminded me of the searchlight of a battleship.

‘But after I got my duties over I returned to bed and thought nothing more about it.’

A policeman also saw the light which ‘seemed to be revolving on a pretty wide area’, then ‘suddenly faded’ around 3am, at which point ‘it was travelling in south-easterly direction’. That same night, something was also seen at Pitlochry in Perthshire:

On Thursday night [27 February 1913] the attention of a Pitlochry residenter was directed to an unusually bright light in the west, described as being ‘like the moon with a haze over it.’

The object looked too large for the star Venus, and appeared to have a shadowy substance behind it.

At the moment the phenomenon was not associated with the rumour of airships being observed at various points of the country, but the matter is at least of interest as being suggestive of a possible northward flight of a mysterious aircraft, as after a short interval it was found that the light had disappeared.

The airship seen at Ardwick in Manchester is reported by one of the witnesses, W. H. Webber, in a letter to the Manchester Guardian (p. 6):

While walking along Devonshire Street, Ardwick, last night (Thursday) [27 February 1913] I saw what I took to be an airship sailing in the sky. It carried two head lights and one tail light. The time was 9 10 p.m. There were scores of people looking at the object. After supper at home, about eleven o’clock, I went out into the street and found a considerable number of people engaged in watching the movements of a flying machine of some sort in the sky, directly over the houses. This letter can be verified by scores of people who were in Devonshire Road, Ardwick, on Thursday night last, or by a good number of people who live in the vicinity of Ashton New Road. I do not, of course, say that this was an airship of any kind, but I did see the lights. The ship finally sailed away due west.

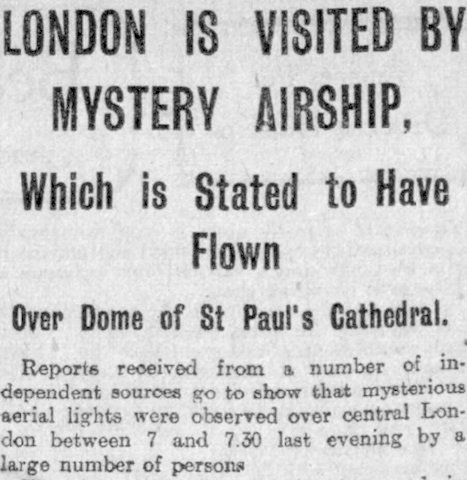

A couple of the airship reports in the Guardian‘s list are also new, but unfortunately few details are given. Both took place near Manchester on Wednesday, 26 February 1913; one was at Hyde (‘flashing lights and long, dark, moving object seen’), the other at Romiley (‘nine distinct flashes of vidid searchlight seen’). There are also some new reports not listed in the Guardian. The Irish Times reports that (p. 8)

A mysterious aeroplane was seen passing over Dublin on Thursday evening [27 February 1913]. It was observed with a large headlight from the Hermitage Golf Links at Lucan about 9 30 p.m. It was flying at a height of about 300 feet, and appeared to be making in the direction of the Curragh.

There are two reports in today’s Norfolk News, one new, one old. The new one took place four days ago:

Mr. Arthur Gouldby, of Kessingland, observed an airship pass over the village on Tuesday night [25 February 1913]. It was at about 9.15, and Mr. Gouldby called several other people to witness the occurrence. The airship came from a N.E. direction, i.e. from over the sea, and turned inland, disappearing in the direction of Beccles. The night was clear, and the outline of the aircraft was distinctly made out by the watchers.

And the old one four months ago:

Sir — The sceptic is welcome to his opinions as to the credibility or otherwise of statements in the public Press as to the presence of airships on the East Coast of late. For my part I am not inclined either to join him nor yet those who dub all jingoes who simply state what they have seen. I will relate my own experience. A few months ago, when there was not then the fuss made as is now of aircraft, I was standing on the Lighthouse Hills at Cromer. It was a fine Sunday in mid-October [13 or 20 October 1912]. The sky was overcast by greyish cloud. Looking seaward, in the direction of the Haisbro’ Sands, was seen a considerable distance out and at a very high altitude, what in shape had every appearance of a Zeppelin airship. How long the object had been there I cannot say, but it remained stationary, so far as the naked eye could tell, for some quarter of an hour. Then taking an easterly course it was lost to sight.

— OBSERVER

Having begun with an artistic response to the scareships, it seems to appropriate to end with some more. The first is a poem by Lucio, the Manchester Guardian‘s regular columnist (p. 7):

‘TWINKLE, TWINKLE’: NEW VERSION.

Twinkle, twinkle, little star,

How I wonder what you are;

Up above the world so high,

Like an airship in the sky?Less suspicious days than these

Gazed on you with greater ease;

But the more I watch you glow

All the more alarmed I grow.What should be your feeble light

Seems to me too clear and bright,

And — I surely cannot err —

Don’t I hear propellers whirr?Don’t I hear a chantey sung

In some strange, outlandish tongue?

Don’t I spot the mate and crew?

Goodness me, I’m sure I do!O what terrors lie in wait!

O our land’s defenceless state!

O — but I can plainly see

This is not the place for me.Better hie me home to bed,

Wrap the covers round my head,

And compose, in much distress,

Gruesome letters to the Press.

The other is a comic strip from the Yorkshire Gazette (p. 2):

They pretty much speak for themselves.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback: Monday, 3 March 1913

Pingback: Tuesday, 4 March 1913

The aerial fleet was seen as very similar to a navy fleet, with the large airships acting as battleships. Of course one links imagination to what he already know. Fashinating.

Yes, it was very common to compare Zeppelins especially with dreadnoughts, especially since they were about the same length. But very misleading, too, since a Zeppelin was far less powerful and far more vulnerable than a dreadnought. As you say, it was natural to think try to understand these new technologies in familiar terms — naval strategy was also an early influence and measuring seapower in terms of dreadnoughts carried over easily into counting airships (and, later, bombers).

Pingback: The Science Fiction of Drone Hype ← Joshua Foust

Pingback: Thursday, 6 March 1913