[Cross-posted at Society for Military History Blog.]

New York waited for an air raid in June 1918. For thirteen nights from 4 June, much of the city was blacked out to avoid giving German pilots any assistance in locating targets to bomb. The New York Times reported the following day that:

Electric signs and all lights, except street lamps and lights in dwellings, were out in this city last night in compliance with orders issued by Police Commissioner Enright at the suggestion of the War Department, as a precaution against a possible attack by aircraft from a German submarine. A system for signalling by sirens in case the approach of aircraft should be detected was devised by the police and signal officers yesterday to warn persons to get under cover.1

While coastal and anti-aircraft batteries readied their guns, aviators went up to check the effectiveness of the blackout, resulting in its extension. After the third night, it was reported that

The lower part of the city was in almost complete darkness, the number of street lights being reduced and those that burned being dimmer. Every downtown skyscraper was almost entirely dark, the shades in the rooms which were lighted being drawn.2

City officials met to discuss other civil defence measures, including air raid sirens and shelters. A particular concern was the evacuation of skyscrapers during business hours:

It was pointed out that in case of such a raid in the daytime the danger of loss of life from panic in swarming down the stairs and into elevators would be greater than the danger of bomb explosions.3

It was decided that the best thing to do would be to designate certain floors as evacuation points. These plans were probably not put into effect, however, as the last night of blackout was 16 June; on 17 June all police precincts were ordered to ‘Resume normal lighting throughout the city until further orders’.4 There was evidently some embarrassment now, as the War Department and the New York Police Department each claimed that the blackout was the other’s idea. In any event, the exercise doesn’t seem to have been repeated.

It’s hard enough to conceive of an aerial attack on New York in the Second World War, let alone the First when aircraft were far more primitive. But for a time, the idea was taken seriously. The context was the campaign of the German U-boat cruiser U-151, one of the largest and longest-ranged submarines of the war, off the eastern American seaboard in May and June of 1918. On 25 May it sank three ships off Virginia, and then on 2 June it had a spectacular run of luck, sinking half a dozen ships off New Jersey. The war coming so close to American shores was understandably concerning, but coupling the submarine menace to the aerial one was something else again.

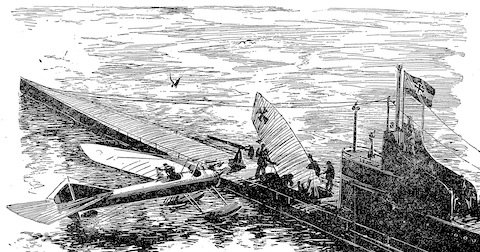

I’m not sure where the idea came from. A book written after the war implies that a a newspaper article by Admiral Peary on ‘the possibility of seaplanes being launched from an enemy submarine to bomb the large cities’, apparently in a Washington, D.C., newspaper, was responsible, supported by a statement made by the president of the Aero Club of America, Alan R. Hawley.5 I haven’t been able to locate these, but I did find an article in the Washington Post on 2 June by Charles W. Duke entitled ‘Will the U-boats come to America this summer?’ The fact that a German submarine was already operating in US waters was not made public until the following day, so this article — and the accompanying illustrations, which I’ve reproduced here — may actually be the origin of the scare. Duke begins:

NOTHING would so please the fatuous sense of humor and so assuage their truculent egotism as to be able to send some of von Tirpitz’s heralded new supersubmarines across the Atlantic to bomb American coast cities with gas shells and lyddite grenades that might be launched a hundred or more miles off New York, Boston or Charleston from the decks of the U-boats, or possibly fabricated hydroairplanes assembled on the surface of the sea alongside the transatlantic ‘unterseebooten.’6

Duke doesn’t offer any specific evidence that Germany has the capability or the intention to do this. Instead he notes its announcement that it now possessed a fleet of ‘supersubmarines’ similar to the Deutschland which broke the Allied blockade by sailing into Baltimore harbour when the United States was still neutral. He also invokes the pillaging of Belgium, the Gotha raids on London and the recent use of the Paris Gun to argue that:

the German has excelled in the most fiendish form of frightfulness — calculated, in the German mind, to break down the morale of the opposition. Thick-headed Prussianism has thought to break the heart of the enemy by the institution of a reign of terror against women, children and noncombatants.7

He is quite sure that, for example, ‘the explosion of gas shells among several of the sanatoriums for children that dot the Jersey coast from Atlantic City to Cape May’ would fail to achieve this objective just as other forms of German ‘frightfulness’ have failed elsewhere.7 But all the same he seems to actually wish for it:

Nothing would so galvanize the fighting American sprit as the spectacle of a U-boat turret looming up out of the mists of the Atlantic. The rays of its searchlights would shoo the few remaining pacifists out of their dark corners and straighten out the kinks of those minority mollycoddles from Missouri who have yet to be actually shown that there is a war.

Let the super U-boats drop their bombs on Bunker Hill monument, Grant’s Tomb, the Liberty Bell or the White House. Each new symbol of ‘kultur’ is but a fountain of oil poured on the flame of American patriotism.7

On 21 July, another U-boat, U-156, surfaced off Orleans, Massachusetts, and shelled the town, albeit quite ineffectually, so Duke wasn’t completely off base.

What interests me most about all of this is that something very similar but also quite different was happening at almost this exact same moment, on the other side of the world, in Australia. I won’t go into details because I’ve discussed this episode at length before, but the threat there was from seaplanes flying from a German surface raider, which supposedly had already happened once in 1917. Here there was also the hope that the feeling of vulnerability created by the possibility of a German air attack on Australian cities would rally support for the war effort. While coastal defences were activated and scratch aerial reconnaissance patrols organised, Australian cities weren’t blacked out like New York. That may suggest that Australians were less worried about an attack than Americans. On the other hand, Australians, in their hundreds, all across the country, actually thought they saw German aeroplanes flying overhead between March and May 1918. This might seem remarkable, but this sort of thing was actually a surprisingly common reaction to the threat posed by the new technology of flight when primed by the press (including, in the United States, in 1896, 1897, 1909 and 1910, and earlier in the war).8 So what intrigues me is why New Yorkers didn’t, as far as I can tell, also see mystery aeroplanes when they were effectively being told to expect them?

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- New York Times, 5 June 1918, 1. See also Paul G. Halpern, A Naval History of World War I (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 431. [↩]

- New York Times, 7 June 1918, 2. [↩]

- Ibid., 15 June 1918, 6. [↩]

- Ibid., 18 June 1918, 24. [↩]

- William Bell Clark, When the U-boats Came to America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1929), 78-9. [↩]

- Washington Post, 2 June 1918, SM2. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩] [↩] [↩]

- See, for example, Stephen Whalen and Robert E. Bartholomew, ‘The great New England airship hoax of 1909’, New England Quarterly (September 2002), 466-76. [↩]

Because more New Yorkers knew what aeroplanes actually looked like, so were less susceptible to seeing them when they weren’t there?

Yes, that definitely could be part of the answer. It’s clear that mystery aircraft scares were more common when the relevant technology was new and hence unfamiliar (airships from the late 1890s to the early 1910s, aeroplanes from late 1900s to late 1910s, rockets in the late 1940s). And there would certainly have been far more aircraft in the New York area than in the whole of Australia, in 1918 and the preceding years. Still, there still would have been many people (in absolute terms, many times more than in Australia) who weren’t familiar. Also, there were a lot of aircraft flying about looking for submarines and looking at the blackout, and in the Australian case the aircraft out searching for the Germans were sometimes identified themselves as German ones, which does not seem to have happened in the US case — there was one report of a USN (?) seaplane landing off the Jersey shore with engine trouble, I think, and the curious beachgoers apparently had no thought that it might be German. (The difference here might be that the Australian air search was not publicised while the American one was.) And add to that the civil defence campaign and the novel experience of seeing the night sky without the interference of the city lights and I’d still expect people to imagine aeroplanes.

But, it might be that astronomical angle that helps explains ‘why not’ too. In the Australian case (which began in March and more or less ended about the start of May, so a month previous to the New York blackout), Venus in the mornings and Jupiter in the evenings were clearly the cause of many of the sightings. In New York by the start of June, Jupiter is already below the horizon in the early evenings; Saturn is up but it’s high and not that bright (magnitude 0.6). Venus is around as a morning object and quite bright but it has to compete with the Moon in the first week or so of June (though it was waning; new moon on 8 June). So perhaps the astronomical conditions weren’t so favourable this time around either.

Could just be one of those things, too!

Pingback: Bomben auf Amerika? | Airminded