One of the fun things about historical research is finding something when you’re not looking for it. Alan Murdie, in his regular ‘Ghostwatch’ column in a recent Fortean Times, wrote the following:

At Folkstone [sic], in 1917, candles in an air-raid shelter were mysteriously extinguished amid other poltergeist events. Natural gas from strata was blamed.1

My eyes lit up at the mention, not of a poltergeist, but of an air raid shelter, for these were quite rare in the First World War. As it doesn’t have much to do directly with the air war, I won’t go into the polt itself, though it does sound a nasty one; but here’s a press summary:

All Folkestone is talking about ‘Spooks’ and a mysterious affair at Cheriton.

Mr Jacques, owner of an ancient but renovated house known as Enbrook Manor, decided to have a wine cellar made in his garden, which would serve also as a shelter during air raids. He employed a local working builder, Mr Rolfe, who soon found himself the victim of annoying interference and a few hard blow from pieces of rock in the cutting.

At first he took little notice of his candle being blown out time after time by a thin blast of white sand. Nor did the fact that streams of sand were blown down his back cause him more trouble than the fashioning of a canvas helmet and neck cover. But when his candle began to move in the air without apparent human agency, and pieces of rock 25lb. or so in weight, and a sledge hammer weighing as much, and a pickaxe with awkward points, he began to wonder.2

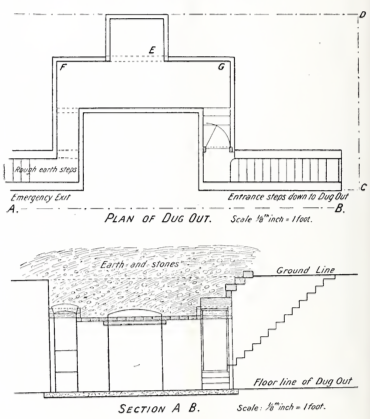

As a nine day wonder, the Folkestone (or Cheriton) spook proved successful enough to draw the attention of physicist W. F. Barrett and physician Arthur Conan Doyle, both experienced psychical researchers who were each soon to ascend to greater heights of credulity (in relation to Glastonbury and Cottingley, respectively). From his investigations at Folkestone, Barrett, along with local electrical engineer Thomas Hesketh, wrote an article for the Journal of the Society of Psychical Research, which along with much evidence and analysis of the poltergeist itself, contains the above schematic of the wine cellar-cum-air raid shelter (or ‘dug out’) itself.3 Win!

Now, being interested primarily in the paranormal aspects of the case, none of the articles say much about how the dug-out was meant to function as an air raid shelter. But a few features are apparent. First, it’s quite simple: just one narrow room, with a recess to one side (presumably for stores or perhaps a toilet). Probably enough just for the family and servants, depending on whether there were chairs or beds. Second, there’s an emergency exit, in case the main stairway is blocked by rubble. Good idea. Third, the entrances are both angled which is a sensible way of guarding against splinters or other flying debris. Fourth, the roof is covered with ‘earth and stones’, with a ceiling of an unknown material which doesn’t seem to be shored up in any way. Other than that it’s mostly a fairly sensible dual-purpose shelter.

Nor is much information given about H.P. Jacques or why he decided to build the dug-out. From the press it’s clear he was a JP and a councillor, so clearly a man of some local importance. Enbrook Manor is now a Grade II listed building, ‘Outwardly C19 concealing a C14 core’.4 The most important fact is the location. Cheriton is a suburb of Folkestone, on the southeast coast of Kent. Not only was this corner of the country in near-constant danger of raids from German aerodromes in Belgium (as was nearby Ramsgate, with which I am more familiar), on 25 May 1917 it suffered one of the most terrible raids of the war when it was struck in broad daylight by the first Gotha raid. Ten bombers dropped 159 bombs and killed 95 people, most of them shoppers on busy Tontine Street, 25 of them children. Another 192 people were injured.

In his official capacity as chair of a meeting of the Cheriton Urban District Council (then separate from Folkestone council) soon after the raid, Jacques ‘said he believed he would be interpreting other members [sic] feelings as well as his own in refering [sic] to the recent air raid and the loss of life, injuries, and destruction it had caused.

There was one aspect of the raid that appealed to them all, and that was the apparent non-preparedness to meet it. Without passing any reflections on any individual it was difficult, with the facts before them, to find where any preparations had been made to ward off such a calamity, and all he could say – and he felt it represented their views – was that it was disappointing in the extreme. However, the Folkestone authorities, together with the Mayor, were taking action on the right lines, and their ejorts [sic! efforts] would be crowned with success.5

Unfortunately I didn’t get to look at Folkestone’s archives in my research trip last year, but according to a postwar history there was indeed considerable civil defence activity after the raid:

The provision of dug-outs or shelters was another subject which engaged the attention of the Council, and eventually refuges were specially constructed at the top of Marshall Street, the rear of Mead Road, the sandpit north of Radnor Park, the basement of unfinished houses in Cheriton Road, Morehall, Mr. Scrivener’s coal stores (under Radnor Bridge Arch), Darlington Arch, the old lime kiln at Killick’s Corner, and a dug-out in the chalk hill on the north side of Dover Hill at Killick’s Corner. The basement of the Town Hall, the Technical School, Sidney Street Schools, the Grammar School in Cheriton Road, the store under Mr. Reason’s house, there being a concrete floor, and the new garage on The Bayle (used at that time as a military guard room), it having a concrete roof, were also open to the public after an alarm had been received. The Martello Tunnel, near the Junction Station, was also used as a shelter, the Railway Company running a train into it for the accommodation of those wishing to take cover there. At the time there were no trains running to or from Dover, owing to the line having been wrecked by the landslip at the end of 1915. The shelter under the Leas Parade (near the lift) was also available as a refuge.6

As was so often the way of things, these measures designed to assuage anxiety created further anxiety themselves:

Later in the year the very existence of these so-called shelters caused the authorities a good deal of anxiety. When the air raids were ‘in full blast’ the basement and Police Court at the Town Hall, for instance, were full night after night. Many people would wait near the Town Hall for the first note of the siren. But even those who were not experts in such matters thought that the Town Hall (like most other buildings used as shelters) was not bomb-proof, and that a direct hit on the building would result in a catastrophe involving terrible loss of life. Ultimately a military expert was consulted, and his opinion was a sweeping condemnation of the shelters. His view was that there was only one which was bomb-proof, viz., the dug-out in the chalk hill at Killick’s Corner.7

Fortunately, Folkestone never received another raid on the scale of 25 May 1917.

Obviously there was a lot going on here, and if I were a different kind of a historian I might be tempted to suggest that the Folkestone poltergeist was some kind of subconscious projection of the fear of air raids. But clearly I’m not that kind of historian, so I’m afraid the causes of the Cheriton affair must remain an open question.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- Alan Murdie, ‘Put that light out!’, Fortean Times, June 2025, 18. [↩]

- Daily Chronicle, 3 December 1917, 6. [↩]

- W.F. Barrett and Thos. Hesketh, ‘The Folkestone poltergeist’, Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, April-May 1918: 155–182. [↩]

- Actually it says ‘CI9’ and ‘CI4’ but that makes no sense. [↩]

- Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate, and Cheriton Herald, 9 June 1917, 3. [↩]

- J.C. Carlile, ed., Folkestone during the War: A Record of the Town’s Life and Work (Folkestone: F.J. Parsons, Ltd., 1919), 123. [↩]

- Ibid., 123-124. [↩]