[Cross-posted at Society for Military History Blog.]

Today is Anzac Day, the anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli of Australian (and New Zealand, though my remarks here mostly pertain to my own country) troops on 25 April 1915. In the last two decades Anzac day has increasingly been seen as marking the coming of age of the nation, and its annual commemoration has become the most sacred event on the national calendar. And as a military historian I think this is a problem.

The original diggers are gone now, and the numbers of the veterans of later wars are diminishing rapidly too, but dawn services at local war memorials and overseas battlefields seem to only become more popular. Broadcast, print and social media are filled with ritual invocations to never forget. New forms of commemoration appear. Stories of courage and sacrifice are told and retold. This is not in itself a problem. I’m not against Anzac Day, as such, and there’s nothing wrong with remembering. It’s what we’re not remembering, or never knew in the first place, that is worrying. We should be looking to understand, not merely remember.

For all the remembering of Gallipoli that goes on, there’s precious little understanding of the campaign. The British took more casualties than the Australians, yet in our version of the story the British are to blame for sitting around drinking tea while their generals sent our boys over the top in senseless attacks: it was one of our own commanders who did that. We weren’t fighting Turkey but the Ottoman Empire, and Johnny Turk probably wasn’t Turkish at all. The role later played by the Ottoman commander at Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in founding the modern Turkish state is sometimes noted, but not the role played by the Allied attack on the Dardanelles in precipitating, or at least justifying, the Ottoman government’s repression of the Armenian people. And why Australians were there at all? The main idea seems to be that they were defending Australia, or democracy, or maybe that they were fighting injustice. Either way, we should be grateful to them for the freedoms we hold today. No doubt these reasons explain why some of the Anzacs fought, but patriotism was surely more important, as was the desire for some adventure and travel as well as simply getting a job.

It is anyway difficult to understand how invading the Ottoman Empire could defend Australia, but in any event Australia didn’t join enter the war for that reason: it joined it because it was part of the British Empire. Australia itself was hardly united during the war: disillusionment increased as it wore on. Two incredibly bitter referenda in 1916 and 1917 on whether or not to introduce conscription were interspersed with equally bitter strikes and strike-breaking, including the so-called General Strike of 1917, followed by an outbreak of sightings of imaginary German aeroplanes at a moment when the war appeared to be lost. Our contribution to the war effort earned us international respect, which we used at Paris to prevent the inclusion of a racial equality clause in the Covenant of the League of Nations. This shouldn’t surprise: the right to keep Australia white was one reason for fighting in the Second World War. But it does.

There are plenty of other things we don’t remember or don’t know about our military history. That the British took this continent from its original inhabitants by force. That ‘Breaker’ Morant was a war criminal. That we didn’t break the German Army in 1918, or that Monash didn’t win the war. That the Japanese never planned to invade Australia. That we panicked when Darwin was bombed. That we weren’t outnumbered at Kokoda. That we bombed Dresden. Some of these things are admittedly uncomfortable to dwell upon, which is the other problem with the rise of commemoration. The endless, ritual invocation of the Anzac spirit (including such supposedly inherently ‘Australian’ characteristics as courage, humour and mateship) and the reverence for the fallen leads to an intolerance for any dissenting views and a consequent deadening effect on inquiry. Criticising ‘our boys’ in any way is fraught with peril, because in the popular imagination they were all heroes, or victims, or both: never villains, certainly. As a historian, I reject this. Soldiers are just people, with all the virtues and weaknesses that implies. Veneration helps us to understand them not at all. Conversely, by focusing so heavily on the masculine and military Anzacs as the founding story of our nation we neglect other, more inclusive and peaceful stories we could tell: for example, Australia as a pioneer social democracy, being among other things one of the first countries to give women the vote. Australia is hardly alone in constructing an exclusive national myth from the experience of war, but it is perhaps telling that Angus Calder drew on Anzac in his introduction to The Myth of the Blitz.

This is moving into the realm of politics. The conservative prime minister John Howard did much to promote Gallipoli and to embed it in Australian culture, partly as a response to what he saw as ‘black armband history’ (particularly the increasing awareness of historical and indeed ongoing injustices to Aboriginal Australians). A federal election later this year is likely to bring in a new, conservative government, and we are promised that restoring the Anzacs to their rightful place in the school curriculum will be a priority, as though we somehow don’t talk about them nearly enough. It looks like the second history war is about to begin.

Further reading: Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, What’s Wrong with Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History (Sydney: NewSouth, 2010); Craig Stockings, ed., Zombie Myths of Australian Military History (Sydney: NewSouth, 2010) and Anzac’s Dirty Dozen: 12 Myths of Australian Military History (Sydney: NewSouth, 2012).

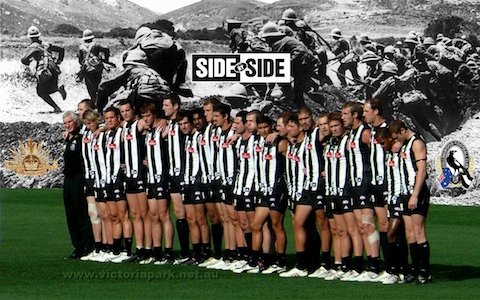

Image source: Victoria Park. This was used to promote the 2010 Anzac Day clash between the Collingwood and Essendon Australian Rules Football clubs; this year witnessed the extension of this ‘tradition’ (est. 1995) across the Tasman, with Sydney and St Kilda playing a game in Wellington. Ironically, while the background image was taken at Gallipoli, it is not of Australian troops at all: it shows men of the Royal Naval Division practising going over the top.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

I have some doubts about the “Australian-ness” of the Anzac troops.

In 1912 my grandfather and his brother arrived in Australia from England. In 1915 they both enlisted and were sent to the Western front as members of the AIF. My grandfather was severely wounded at Pozieres, his wounds contributing to his death many years later. My great uncle was killed at Passchendaele.

If they ever pondered their nationality (which I think is unlikely), I doubt that either of them considered themselves as Australian or fighting for Australia. More likely they were defending the Empire and their homeland where their mother and brothers still lived. Like the iconic Anzac, John Simpson Kirkpatrick, they were miners from north-eastern England.

I would suggest that in celebrating the “Anzac” spirit we are actually celebrating the strengths of the British working class.

Excellent post, Brett, catching a lot of my reservations about the current style of growing commemoration. The current commemorations of ANZAC have very little to do with history, and much to do with what Snopes calls a ‘glurge’ – though with live participation.

Bean (and to a lesser extent, K Murdoch) would probably be amazed at how his mythologising to increase the status of Australian manhood had grown. But of course it’s a very flexible myth and commemoration (like a flag over the shoulders of a thug on a closer beach or a sportsperson) despite the pretty conservative standard narrative.

And at “…never villains, certainly…” I think you missed: http://airminded.org/2010/06/30/mates/ here, rather than earlier in the post.

As to the Australian-ness of the ANZACs, it depends on who’s looking and what they want to see. Australia’s current prime minister was born in Wales, one of our best recent defence chiefs was born in Scotland, and they are both Australian citizens. It’s still an immigrant’s nation, and a lot more complex and diverse then, as now, than most myth-peddlers wish.

Thanks for encapsulating many of my reservations about ANZAC day and the way we commemorate it.

Ken:

Interesting comment. There’s something in what you say. The British influence was everywhere in Australian society. Many Australians had been born in Britain, and even those who had not and had never been there though of it as ‘home’. I’ve noticed that during the war, many Australians described themselves as ‘Britisher’ rather than ‘Australian’, though this may also have been in implicit opposition to ‘German’. Certainly the majority would have seen any contradictions between being simultaneously Australian and British (if colonial). But there were exceptions: notably the large proportion of the population which was of Irish Catholic descent (and this became a problem after Easter 1916). And I think Australians did already feel they had a distinctive identity by 1914, and also the war strengthened the sense that they were different from the ‘old country’. By 1939 this had sharpened again, though great loyalty was still felt to Britain, and continued to be for some decades. So — it’s complicated. One book I might have cited in the post has much to say on this question: E. M. Andrews, The Anzac Illusion: Anglo-Australian Relations during World War I (Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1993). Also, Philip Payton, Regional Australia and the Great War: ‘The Boys from Old Kio’ (University of Exeter Press, 2012), in part provides a useful case study of one particular British immigrant community (i.e. the Cornish) had adapted to Australian conditions and responded to the war.

JDK:

I hadn’t really come across ‘glurge’ before, but I like it! Yes, that’s exactly how so many of these tropes are spread, and social media is a great enabler. You’re right that, like all good myths, Anzac is a flexible myth; in recent years it has grown to include women (i.e. nurses), and there’s now an effort to bring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in too. I guess that’s partly what gives it power, that it changes with the times; it’s also what gives me some hope that it can be changed…

At ‘villains’, I actually was going to put in a link to something about Peter Stanley’s book Bad Characters: Sex, Crime, Mutiny, Murder and the Australian Imperial Force (Millers Point and London: Pier 9, 2010) which has that same photograph on the cover, but couldn’t find anything good and ran out of time. So I see the connection. But that post really was more about critiquing the elevation of ‘mateship’ in Australian discourse than showing that there was riffraff in the AIF; anyway given the current tendency to see the diggers as victims as much as heroes, deserters might not even be seen as villains. So it’s better where it is. (Though now that I think about it, there’s no law against linking to the same post twice!)

Heath:

Thanks — I think I’m only saying what a lot of people are thinking! And have said before, see the further reading. But it needs a lot of saying. So to speak.

The mythos often overtakes the reality and eventually becomes the reality. It happens even with history; a claim by one historian is repeated without checking and referenced by others assuming the status of a ‘fact’. Emotional appeals to history do not themselves make good history but prove more satisfying. Eventually a whitewash of the complexity of reality occurs. One wonders if this is what is happening here?

There’s a bit of that, certainly. Popular histories (which these days seem to be mainly written by journalists) uncritically recycle old stories or add new angles (my ‘favourite’ is a book called Monash: The Outsider Who Won a War). Then there’s C. E. W. Bean, who was a war correspondent and then wrote 6 volumes of the Official History. As JDK indicated, he played an important role in tying the Anzacs to idealised visions of bronzed Aussie bushmen towering over their stunted British cousins (I’m paraphrasing!) The fact that Bean is still regularly cited and quoted even in popular accounts of the Anzacs, whereas the British official historians are largely forgotten except by academic historians, suggests something of his influence.

But nationalism is perhaps just as, perhaps more, important. Or maybe just politics. I don’t remember Anzac Day ever being that important when I was at school; it seems like it was in the late 1990s and 2000s, under the Howard government, that it began its resurgence, alongside a brittle nationalism (e.g. every school now has to fly the Australian flag, thanks to Howard). On the other hand, it’s also been argued that it was previous Labor governments (Hawke was the first PM to make the pilgrimage to Gallipoli for Anzac Day, in 1990) which began to see its uses, especially in the lead-up to the Bicentenary of white settlement in 1988, because it wasn’t as problematic as the ‘other’ national day, Australia Day, which celebrates the anniversary of that white settlement and so is not highly thought of by indigenous Australians who often call it Invasion Day. (Keating, the Labor PM between Hawke and Howard, tried to promote Kokoda instead of Gallipoli, as that suited his push for a republic; that didn’t happen, though it has grown in popularity too.) This suited Howard perfectly, who consistently derided what he termed ‘black-armband history’, sought to limit previous land rights legislation and dismissed calls for even symbolic gestures of reconciliation. But he also clearly had a genuine attachment to the Anzac legend (witness his idea of enshrining ‘mateship’ in the Constitution’s preamble). Anzac, Gallipoli, etc, were part of his vision of and for Australia, and will always be identified with him. Having said that, it wouldn’t have taken hold if he wasn’t speaking to and for a large section, perhaps the majority, of the Australian people. So it’s not just him, either.

Anyway, What’s Wrong With Anzac? is good on these issues, though by its nature it’s something of a polemic.

Pingback: ANZACs | life and fate

I have recently studied Gallipoli for my Honours. I took a different view on pilgrimages, not modern ones, but those made by relatives, mates and comrades in arms. There are so many theories about the what and why of Gallipoli, the men who went, why they did and what happened to those who came home. I do not believe that Anzac Day is irrelevant at all. What I find disturbing is that Gallipoli became a ‘had to’ event on backpacker lists of things to ‘do’. Yet so many of those did not understand Gallipoli was a defeat and not a victory!!! Which comes back to me about how and what is taught in Australian schools about history. However, having researched so much about Gallipoli, the campaign, the deaths and the aftermath so many of those men and families, I believe deserve the honour we continue to give them. The rate of suicide and incarceration in mental hospitals was horrific.

There was also so much censorship over news reports over Gallipoli that most families believed their sons had died ‘ a noble and brave death’ which in fact probably meant he had been blown into oblivion. Most families would never see where their sons graves, and spent most or the rest of their lives ‘imagining’ their graves, the cost and time spent traveling to Gallipoli meant only the wealthy of Australia could make the journey.

Thanks for your comment, Christine. One quibble: I’m not saying that Gallipoli is irrelevant, more that it’s too relevant — that is to say, because we collectively have made it so central to our national self-image to the exclusion of other things. It certainly should be part of our story, just a less prominent part. But I agree with what you say about the lack of understanding on the part of those taking part in these commemorations (generally speaking, of course, it’s not true for everyone). That’s the danger with rituals — over time they tend to be performed for their own sake, and the original reasons are forgotten. We do them because we always do them, and because everyone else does. Maybe the National Curriculum will help where the next generation is concerned, though that’s probably optimistic!

Christine said: “…Yet so many of those did not understand Gallipoli was a defeat and not a victory!”

That also contains another very interesting point. The fact that, however you cut it, the Gallipoli campaign was an ultimate defeat for the Allied powers*, and that fact eventually will come up in analysis, however superficial initial encounters are, means that there isn’t the opportunity for the unthinking triumphal jingoism that can occour where a victory is the myth.

I didn’t think there was any new aspect of the Gallipoli story I could find to be A Good Thing, but that actually is.

(*A contrast is the struggle with the concept of defeat by the US in Vietnam, down to today, or Germany’s ‘Stab in the Back’ palliative myth of the 20s and 30s. I don’t believe (beyond raw ignorance) there’s any such struggle or attempt to gloss the ultimate result of Gallipoli in Australia in these ways.)

I agree, up to a point. The problem is that we don’t ‘own’ our involvement at Gallipoli — it wasn’t our decision to fight there, but Britain’s. So we get to blame them for the defeat and the whole issue becomes depoliticised in that sense. The same studied ignorance surrounds our participation in other wars and battles. Ultimately, what happens is that we then focus not on why we fought but on the mateship and the heroism and the martial prowess, and these qualities are then available to be redeployed in another war. Which inevitably they will be, because how else can we affirm that we still have the Anzac spirit?

Funny where things pop up. I’ve seen that photo in a pizza shop framed amongst other Collingwood stuff. The photo is mine (the players, not the soldiers). They are indeed British soldiers and their addition was intentional and a clumsy attempt at a subtle caricature of pretty much everything Brett has written above. I whole heartedly agree with what you’ve said Brett and would add the disturbing modern phenomena which is the over zealous nature of the ‘marketing’ of ANZAC Day and in particular how sport (big business dressed as sport) has taken to the occassion like a duck to water.

Great read and some great comments too. Thank you.

(BTW. My Grandfather was WWI vet. Stretcher bearer on the Somme. Discharged wounded and become a leader with the conscientious objectors movement. I have inherited his politics and views on most things.)

Thanks for your comment, Shane, and interesting to know the provenance of the photo. I agree with you about the over-the-top (so to speak) use of Anzac Day by big sport — I don’t even follow AFL and it’s very obvious to me purely on that marketing level. It does seem to be a relatively recent phenomenon, too, which says something about the way these two great modern secular religions are feeding off each other. Interesting, but not necessarily good.

Pingback: The one day of the century | Airminded

Pingback: A day to remember – Airminded