What was the response to the Canterbury Baedeker raids? There was actually surprisingly little direct comment in the British press, but the major theme was to reaffirm that British raids on German cities were not reprisals but attacks on legitimate targets; whereas German raids on British cities were not even reprisals but merely spite. In a leading article, the Times, said of the RAF’s attack on Cologne that ‘the airmen who demolished military targets hard by were able, by German admission, to spare the cathedral’, whereas

The authors of the so-called ‘reprisal’ raid on Canterbury, having for its sole objective the destruction of historic buildings of great beauty, stand self-condemned.1

Similarly, in the opinion of the Western Daily Press:

While it is easy to perceive a poetic justice in what Germany is now going through, it is not for the purpose of exacting vengeance that the mammoth raids of the R.A.F. are being conducted. Unlike the Germans, who make targets of our cathedrals, we are not interested in destroying the antiquities of the Reich. But we are interested in the centres of German war production, and it against these that the heaviest onslaughts will be directed.2

For the Gloucester Journal, while Bomber Command’s attacks are indeed the ‘fulfilment of the open warning, long since given, that every ton of bombs dropped on Britain shall be returned in ten-fold measure to the Hun’, they ‘are much more than mere reprisals […] They are part, an integral and essential part, of the vital battle of supplies, by which the ultimate issue of the war will be decided’.3 The Bishop of London, Geoffrey Fisher, speaking before the London Diocesan Conference, thought the RAF’s raids justified:

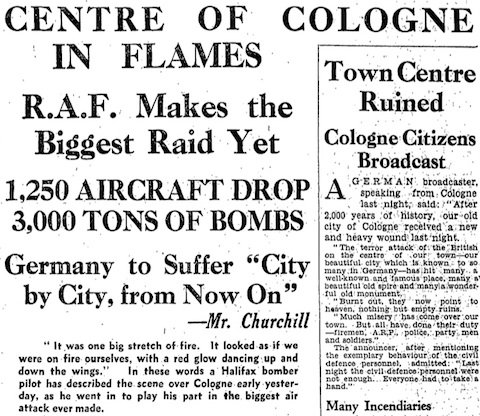

Canterbury and Cologne had each in its own country a very special place in religious life and sentiment. Canterbury had no military significance; Cologne, as a centre of war industries, had, and its destruction on a large scale was legitimate and a legitimate cause for satisfaction.

At least William Temple, the Archbishop of Canterbury, while also not doubting that the RAF’s attacks were legitimate — here speaking specifically of Lübeck and Rostock — added that ‘proper satisfaction must always be accompanied by distress of soul at the misery and suffering inflicted thereby upon thousands of homes’.4

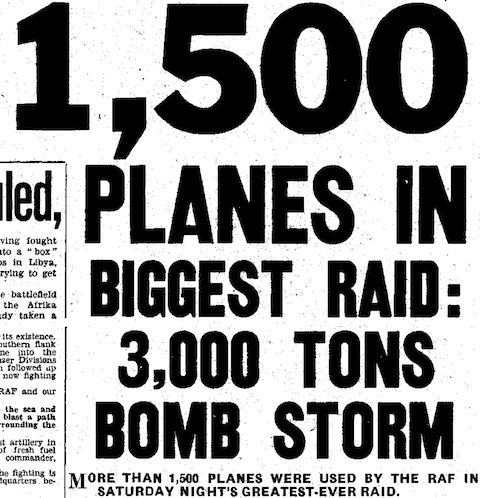

There were competing and even contradictory narratives, however: confidence vs complacency. A number of papers contrasted the scale of the British and German air offensives, to the latter’s disfavour. For the Daily Express, ‘A raid with 50 planes was the German reply to the 1,000 planes sent over the Rhine‘. It pointed out that Canterbury was close to the coast, by implication a less dangerous target for raiders, and this, ‘even more than its Baedeker stars, is the charm of Canterbury for the Luftwaffe raiders’.5 A few days later, Basil Cardew did some number-crunching and found that the Luftwaffe, heavily committed to the Russian front, ‘has not more than 300 bombers spread out from the northern tip of Norway to the Atlantic coast of France’:

As it is, they have only a force sufficient to put over 50 planes a night, and then not more than twice a week.6

A correspondent for the Times, who attempted to analyse the effect British bombing on civilian morale in Germany (short answer: it’s significant but don’t assume that a few more heavy attacks will cause a knock-out blow), noted the way the Baedeker raids were being exaggerated in Nazi propaganda:

Meanwhile the fiction that Germany was ‘returning blow for blow’ was maintained by representing the ‘reprisal raids’ on Canterbury and Ipswich as major operations. The attack on Canterbury and its ‘Bolshevist archbishop’ was announced on the front page of every German newspaper under banner headlines, while a war reporter describing the attack on Ipswich gave an impression of swarms of raiding aircraft and of a town ‘reduced to smouldering ruins.’

There seems to be no awareness that British propaganda might also be misleading, though in fairness it would be hard to top Goebbels’ brazenness in claiming that ‘Not more than seventy’ bombers took part in the thousand bomber raid, of which half were shot down!7

In a speech to civil defence workers in Staffordshire, Herbert Morrison, the Minister of Home Security, also pointed to the ‘increasingly shameless and naked exaggeration of the significance of the Baedeker raids’, with Canterbury, for example, being described as ‘a great centre of transport and industry’:

The whole scale and significance of the raids is magnified 50 times over. Some raids consisting of nothing more than a moderate number of incendiary bombs have been described as though they were large-scale attacks.

But he also warned that:

Since it is obviously considered by the Nazis to be a matter of great importance that they should satisfy the German people that our raids on German cities are being repaid in full and more than in full, the time may come and before very long when they must try to give a more solid basis to their assertions.8

There seems to have been a concerted attempt to make sure that people didn’t become complacent about civil defence. Morrison gave several speeches on the same theme around this time, and Ellen Wilkinson, his parliamentary secretary at Home Defence, told the National Fire Guard Conference at Torquay that ‘we had now reached the end of the comparative lull in German air raids’:

‘We have got to face the facts,’ she continued, ‘and I believe that if a referendum of people in this country were taken it would show bluntly and squarely that we are ready to face it, because we know that such a mass of strength as was shown over Cologne does bring the end of the war appreciably nearer. But we shall not avoid a good deal of trouble, and we must leave this conference steeling ourselves to to face what is coming, and get our people ready and bring our organization to the highest state of efficiency.’

She also suggested that ‘The lessons of the Baedeker raids were that we must revise our strategy and our conception of the vulnerable areas’. This seems to mean compulsory training for fire guards; but Wilkinson also floated the idea of making fire-watching compulsory for women: ‘there were some of the more moneyed classes who had failed to register, and suggested that inspectors “should question some of the ladies you see having ‘elevenses’ in elegant cafés every morning.”‘9 She wasn’t known as ‘Red Ellen’ just for the colour of her hair.

One last reaction, albeit indirect, to the Baedeker raids came in a book review (signed ‘I. C. N.’) of Gerald Cobb’s The Old Churches of London which was published in the Western Morning News:

The author hopes that someone will write a history of City churches in general — not only of London, but Norwich, York, Canterbury, Exeter, &c., for ‘in all these places the numbers are greatly reduced from what they were.’ Recent raids on Cathedral cities certainly emphasize the point.10

So historians had a part to play amid the destruction of culture.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- The Times, 3 June 1942, 5. [↩]

- Western Daily Press (Bristol), 3 June 1942, 3. [↩]

- Gloucester Journal, 6 June 1942, 6. [↩]

- The Times, 9 June 1942, 2. [↩]

- Daily Express, 2 June 1942, 2. [↩]

- Ibid., 4 June 1942, 2. [↩]

- The Times, 11 June 1942, 5.. [↩]

- Yorkshire Post (Leeds), 8 June 1942, 4. [↩]

- Western Morning News, 2 June 1942, 2. [↩]

- Ibid., 19 June 1942, 2. [↩]