In my previous post, I threatened more statistics about Australian mystery aircraft scares of the First World War, and here they are. What I’ve been doing is collating all the sightings recorded in two NAA files, MP1049/1, 1918/066 and MP367/1, 512/3/1319. The former is the Navy Office’s file pertaining to ‘Reports of suspicious aeroplanes, lights etc’, more than a thousand pages in all, though the majority of it is composed of reports obtained by military intelligence and local police. The Navy was presumably interested because, assuming the reports were genuine, the most likely explanation was that the aircraft were flying from a German raider operating in Australian waters. The file also contains some operational orders and reports relating to the search for the presumed raider, regular reports and analyses of the sightings to date, and related correspondence. The other file contains ‘Reports from 2nd M D during War Period on lights, aeroplanes, signals etc.’ 2nd Military District covered NSW; presumably there were similar files from the other districts but if so I haven’t found them yet (3rd MD would be the one to get, as that was Victoria where the majority of sightings took place). Some of the material in it is duplicated in the Navy’s file, but there’s much which isn’t, including a number of pre-1918 reports.

After going through these two files, I now have a master catalogue of 256 distinct sightings, which is nearly a hundred more than are listed in the Navy’s own master index. But the data is quite dirty, I’ve tried to cull duplicate reports, but there are probably still a few in there. The dates are sometimes vague, sometimes only at the ‘about six weeks ago’ level of accuracy. Sometimes a sighting is recorded only in the index (with a very brief description) and can’t be found anywhere else in the file. What constitutes a ‘sighting’ also varies. Sometimes a number of sightings are counted as one, sometimes not: multiple reports from one location usually are, but one at the same time from an adjacent town generally are not; reports over a few days are often considered to be single sightings, but not always. I’ve generally tried to follow the treatment at the time, especially in the indexes and summary reports. But not all cases are listed in those, so I’ve had to use my own judgement. And sometimes, to be honest, I found some handwritten reports almost impossible to decipher and haven’t tried to extract every last sighting from them, just the main details. For the moment that doesn’t matter, I just need to be able to characterise the mystery aeroplane scare in overall terms. A few missing sightings or wrong dates here or there won’t make much difference.

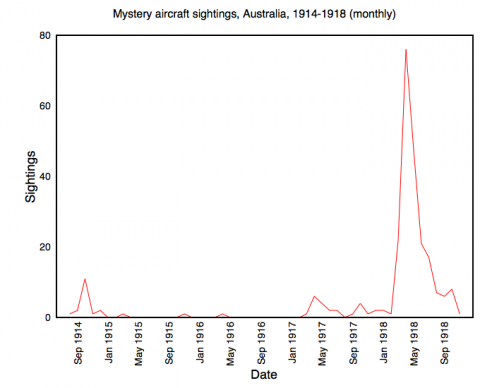

And it’s already proven very educational. I’ve plotted the sightings by month above. It’s clear that, apart from the main scare in 1918 (212 sightings in total — again, don’t take the numbers too literally), there were two or three much smaller outbreaks: one in October 1914 (perhaps corresponding to the departure of the first AIF troopships), one in April-May 1917, and maybe another in October 1917. But it also shows that my earlier understanding of the course of the 1918 scare itself was wrong. Based on reports published in newspapers, I thought it started in March and ended in mid-April. In fact, it was only getting started: the majority of sightings took place after the press stopped reporting the scare. The peak month was April, with 76 sightings; in May this dropped to 48, and in June and July returned to the same level as March, the first month of the scare, at about 20 sightings. The number of reports fell to below 10 for each of the remaining full months of the war, but this was still equal to or higher than any previous month before March 1918 bar October 1914. This means that my suggestion that ‘press reports of mystery aeroplanes themselves helped to propagate the wave of sightings’ will need to be modified: at most they can only have helped kick off the scare. Why did the press not report any sightings after mid-April? Censorship may be part of the answer; I’ve found one case from July where the Sydney censor’s office notified the Navy Office that it had ‘permanently held’ one mystery aeroplane report submitted by the local stringer at Gilgandra to two Sydney dailies. There are other notices from censors but I’ll have to check to see if the reports they passed on made it into the papers or not.

This plot is the same as above, except that the sightings are also plotted by whether they were interpreted as aircraft or signals (e.g. mysterious lights flashing in the hills, or from a ship out to sea, presumably to or from German spies or vessels; sometimes they were supposed to be electrical flashes from wireless stations). It shows that I’m cheating a bit: some of what I’m calling mystery aircraft were not thought of as aircraft at all, or even as airborne in any way. But only a bit: the mystery aeroplanes almost always outnumbered the mystery signals, usually very greatly when there was a scare on (with the exception of the October 1917 scare, which is revealed to be all signals, no aircraft); and when there was a mystery aeroplane scare on there was a rise in mystery signal reports too. So this suggests they are related phenomena, which makes sense — an odd light which is on the ground or on the sea is obviously more likely to be interpreted as something which isn’t an aeroplane. The clincher is the fact that the military and naval authorities at the time put them together under the one heading: they were part and parcel of the same (potential) German threat. This perhaps complicates the role of airmindedness in the scare; but on the other hand it makes it easier to relate mystery aircraft scares to other types of scares, such as the Edwardian spy mania in Britain.

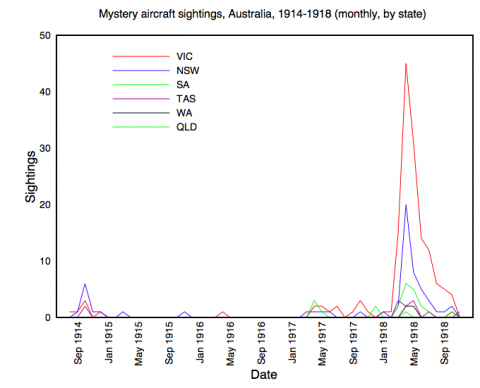

Here’s an initial answer to the question ‘where?’ I’ve broken down the sightings by state (and so excluded two sightings in the Navy’s files not from Australia: one in New Zealand and one in Papua, effectively an Australian colony). Victoria was clearly mystery aeroplane central in 1918, with 133 sights out of the 212 recorded that year. It was probably the primary source of sightings in 1917 too, but only as a first among equals. NSW was the only other state to even come close, and even then it had less than half the number of mystery aeroplane reports that Victoria had in April 1918. South Australia and Tasmania had significant numbers of mystery aircraft reports across the war; Western Australia and Queensland very little.

Victoria’s dominance is a fact which requires some explanation, and I don’t know that I’ve got a convincing one yet. It’s not simply due to population. NSW had the greatest population of any state in 1918, 1.9 million; Victoria was second with 1.4 million — and third was Queensland with 700,000, and it had only two mystery aeroplane sightings for the whole war. Perhaps it had something to do with population density, which was about 2.5 times higher in Victoria than NSW. That is, maybe something odd in the sky had more chance of being seen over Victoria than it did over NSW. But that only works if there were multiple sightings at the same time, which was not the norm (though a couple of the hotspots where that did happen, Ouyen and Gippsland, are in Victoria). Or perhaps rumours spread more easily in more densely-populated Victoria, especially after newspapers stopped printing news of mystery aeroplanes. (Most sightings were from rural districts, but I think this was even more true of Victoria than NSW.) Perhaps Victorians felt more under threat? The temporary capital of Australia, with Parliament and the Department of Defence, was Melbourne, so it could be seen as more likely to be attacked. But that doesn’t explain sightings in far-flung corners of the state and I don’t think people really think like that anyway (the place where you live is obviously the centre of the universe). It’s true that the German raider Wolf had mostly preyed in the seas south of Australia, so maybe the next one would too; but the next one could strike anywhere, and besides, the Wolf‘s seaplane had (supposedly) flown over Sydney, not Melbourne. I’m not convinced, anyway. Perhaps looking at the data more closely will throw something up. Maybe it was the weather.

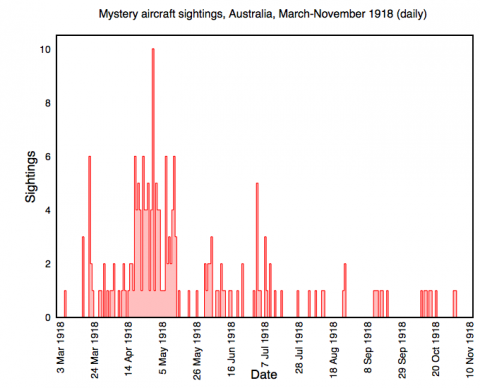

Finally, this is a plot of just the sightings from March 1918 onwards, i.e. just the 1918 scare itself, but here the number of reports are daily instead of monthly. This makes it clear that the peak period of the scare was the month from mid-April to mid-May. More precisely, the scare started around 17 March, kicked into higher gear around 18 April, peaked on 29 April, and halted around 13 May (with a couple of resurgences from 31 May and 2 July lasting a week or two). What else was going on around then? I’ve already suggested that two press stories helped start the scare: the claim that the Wolf‘s seaplane had flown over Sydney the previous year (published 16 March), and news of the successful start of the German spring offensive (published 25 March, though press reports were anticipating it before then). But if my argument that the mystery aircraft sightings were caused, at least in a general way, by anxiety about the war being lost and/or Australia itself being directly threatened, then the big jump from 18 April suggests that there had been further bad news around that time.

And there was: reports of Haig’s famous ‘backs to the wall’ order of the day were first published in the Australian press on 13 April. It’s tempting to follow that logic and try to assign the peaks and troughs in the scare with the fortunes of the German offensive, but it doesn’t quite work. The scare did peter out when the offensive did, by the end of July, and maybe the falling away after the end of April was because the Germans had stopped attacking for the moment. But then why did mystery aeroplanes reappear in the first week of July? That was a lull on the Western Front. There might have been some other reason for anxiety that week; I haven’t looked yet. But the problem with this — and it’s a more general problem with relating specific incidents like mystery aeroplane sightings with broader trends like the course of the war — is that I’m really just guessing here. What evidence do I have that people who saw mystery aeroplanes were particularly worried about the way the war was going? There’s some evidence, but it’s scanty; it’s not something that police constables tended to jot down. This is one reason why I’m attempting, in a small way, a comparative study similar scares in other places and other times: the fear of war, of attack, of spying is common to many of them, and teasing out the similarities as well as the differences between these defence scares will, I hope, strengthen my argument. Or I could just end up arguing in circles.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Might be worth correlating the position of Venus or Jupiter against “lights in the sky” reports?

Indeed! Thanks for prompting me to check. Jupiter was visible low in the northwest until about 7-7.30pm. Venus was a morning object at this time, but interestingly it was near maximum elongation (21 April), meaning it was nearly as bright as it gets (which is to say very bright, apparent magnitude -4) and moreover, visible for hours before sunrise, rising at about 3.30am to the east and fading from view a bit after 6.30am, northeast but very high above the horizon by then (41 degrees from Melbourne). So it’s a double whammy of a very bright Venus in the mornings (and the effect can be startling) and a very noticeable Jupiter low on the horizon at dusk. Perfect conditions for an airship scare, I’d say. I haven’t checked to see whether individual sightings match these but certainly there were quite a few pre-dawn ones which were very bright, which could fit Venus. But astronomy can’t account for everything — there were a quite a high number of daytime sightings too; and very few investigators back them seem to have picked up on Venus/Jupiter as explanations (stars in general sometimes, and birds were sometimes offered). Something to keep an eye on and maybe come back to.

Again, though, this is something I don’t want to get too caught up in. It’s nice to be able to say ‘yeah, they were mostly looking at Venus’, especially since people will ask! But for my purposes I don’t really care what they were really looking at, I’m more interested in why they misidentified what they were seeing. Why did they jump to the conclusion that, of all things, that light wasn’t a planet maybe but a German seaplane? Or a Zeppelin even, which at least three people did? So fortunately for me I don’t need to debunk the sightings in detail in that way.

Pingback: Airminded · Where again?

Pingback: The air raid that didn’t | Airminded

Pingback: Tuesday, 23 April 1918 – Airminded