The Luftwaffe launched mass daylight raids against London and Bristol yesterday, ‘the most widespread of the war’ according to the Daily Mail (1), and with the largest losses since 15 September, too. German losses are reported to be 130 aircraft and about 300 aircrew, while the British lost 34 fighters and 19 pilots. Many people watched the battles from the ground, and ‘cheered as raider after raider fell’.

Bomber Command’s raids seem to be meeting with success, depending on what is meant by success (cf. Illingworth’s cartoon above, from page 2.) The ‘Daily Mail Radio Station’ (i.e. the Mail‘s monitoring of enemy radio stations) says that, according to Italian broadcasts (1),

casualties in Berlin caused by recent R.A.F. raids are the heaviest since the air war began. A total of 1,753 have been killed and 2,049 wounded.

The Mail also has a photo of a British ‘secret weapon’, the ‘”flame leaf” […] which has caused so much terror in Germany’:

It takes the form of an incendiary pill treated with specially prepared cotton wool […] which burns under the influence of oxygen or the sun’s rays.

Supposedly, because of the ‘flame leaves’ being dropped by the RAF ‘Berliners are now required to buy their own gas masks at once’.

So the RAF seems to be getting rather good at this aerial warfare business. And it seems it may soon have the advantage of numbers. Harold Cardozo has met in Lisbon with ‘A famous neutral air expert’ who is apparently familiar with the Luftwaffe and the German aviation industry (6). He says that Germany’s numerical superiority over Britain, while real, ‘is strikingly less than I thought’ and anyway is partly due to dive-bombers which are useless now that there is no land war. Moreover, the Luftwaffe is ‘at present practically incapable of expansion’ whereas the RAF will start to expand ‘on an immense numerical scale as from November next’. The expert (an American?) is also scornful of Germany’s training system and lack of aircrew reserves.

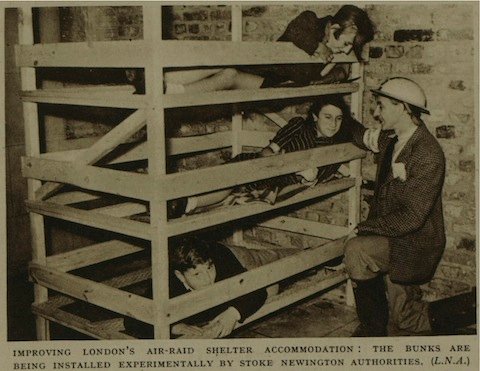

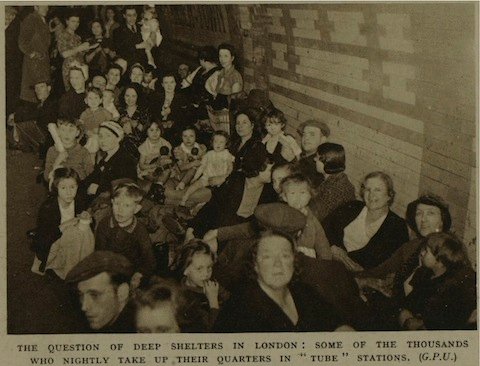

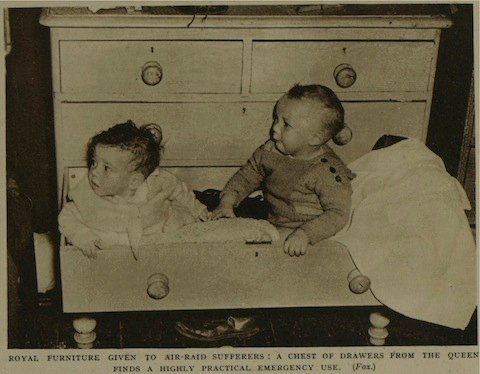

There is also some (potential) good news on the home front. Two ‘air raid dictators’ (the Mail‘s term) or ‘Special Commissioners’ (the government’s) have been appointed for the London area. Henry Willink, KC, MP, is to be responsible for ‘the care and rehousing of the homeless’, while Sir Warren Fisher, former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, is charged with ‘speed[ing] up the clearance of debris, the work of salvage, repair of roads, and the restoration of damaged public services’. Local authorities have also been given powers to requisition basements as ‘day-and-night shelters’. Will these announcements satisfy those who have been calling for ‘dictators’ to cut through red tape and quickly bring relief to the beleaguered people of the East End? Their timing has certainly taken some of the force out of the New Statesman and Nation‘s leading article today, which alleges that those steps which have been taken to date (such as opening Tube stations to shelterers) have been forced upon ‘reluctant Ministers by the overpowering and immediate needs of East London’ (297). It calls for ‘a Welfare Bard which can over-ride the competing and overlapping authorities’. Still, the New Statesman has had a good run on this issue — Ritchie Calder was one of the first to publicise the bureaucratic muddle surrounding post-raid welfare, in last week’s issue, and there is much support for his criticisms in today’s letter columns.

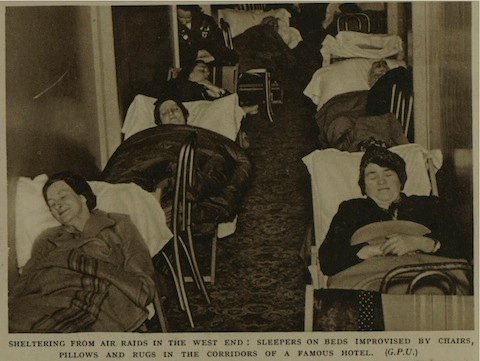

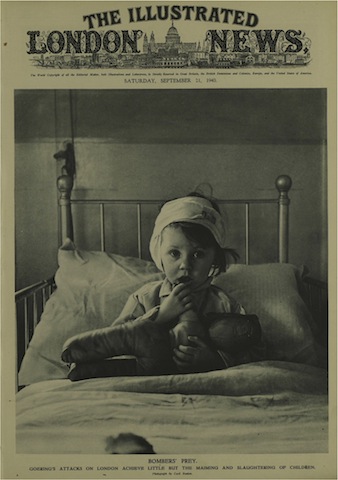

Let’s take a look at life in the shelters. Tom Harrisson, one of the founders of Mass-Observation, has an interesting article in the New Statesman today on how people are adjusting to life under the bombs. He includes a long description, from (presumably) one of his observers, ‘an East End working girl’, of ‘one of the few deep shelters in the East End’ (probably the Tilbury). I’m going to quote it in full (300-1). Compare it with illustrations of ‘Blitzkrieg problems in London’, as printed in today’s Illustrated London News (403).

The structure is colossal, mainly of platforms and arches. The brick is so old, the place so filthy and decrepit, that it would be difficult for the best of artists to convey its ugliness on paper. First impression is of a dense block of people, nothing else. By 7.30 p.m. each evening, every available bit of floor space is taken up. Deck-chairs, blankets, stools, seats, pillows — people lying on everything, everywhere.

When you get over the shock of seeing so many sprawling people, you are overcome with the smell of humanity and dirt. Dirt abounds everywhere. The floors are never swept and are filthy. People are sleeping on piles of rubbish. The passages are loaded with dirt. There is no escaping it. The arches are dank and grim — they are lighted well, until black-out time, and then all the lights on one side are put out, because the black-out arrangements are inadequate.

There they sit in darkness, head of one against feet of the next. There is no room to move, hardly any room to stretch…

The sirens went at about 8 p.m. Lots of people were asleep, but in general it was too early for this.

But already, at 8, people were beginning to cough, and this coughing spread, and lasted throughout the evening. I developed a cough and sore throat, in the early stages of the evening.

Everyone there was working class. The shelter is near the dock area, and near the coloured quarters. Mostly Cockneys, but also many Jews and Indians. On the whole, the Jews lay on the right-hand side, the Cockneys in the middle, and the Indians on the left. Race feeling was very marked — not so much between Cockney and Jews, as between White and Black. In fact, the presence of considerable coloured elements was responsible for drawing Cockney and Jew together, in unity against the Indian. There were a lot of cases of mixed marriages — in fact, it was more usual to see a mixed one, than to see husband and wife coloured. Some of the coloured people were Indian, some Negro, a few Chinese. Some of the Indians, those not occupied with girls, played cards.

Harrisson adds (301):

The only first-aid facilities were provided by a group of men who clubbed together voluntarily; sanitation, some pails behind screens; lighting, medieval. All night long wardens patrol and act as dormitory police. Here, surely, is a new low for urban civilisation? Yet there is really nothing else that people in that area can do. It is not the civilisation they have made, it is the one that has been prepared for them these many years past.

Oh, and the Manchester Guardian finally has a another letter regarding reprisals today. It’s from Ex-Lieut., Machine-gun Corps of Brighton who says ‘Surely we have fought this war long enough in kid gloves’ (4). He thinks the German people need to be taught that ‘these methods of warfare do not in the long run pay’ and so wants a German city to be ‘systematically and ruthlessly bombed’. But since he would have Britain give warnings first, this ‘drastic’ action would only place him somewhere towards the moderate end of the Mail‘s pro-reprisal correspondents.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Very interesting passage on racial segregation in the shelter. Do you know if anybody has done any research into Britain’s ‘non-white’ civilian communities in WWII?

If they haven’t it’s probably about time.

Becky Taylor, currently at Brikbeck, has done research into attitudes towards Gypsies (Roma) in the UK during WW2.

Pingback: Airminded · Sunday, 29 September 1940

Sonya O. Rose, Which People’s War? National Identity and Citizenship in Wartime Britain, 1939-1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), has a lot to say on the subject, particularly in chapter 7.

Pingback: Airminded · Post-blogging 1940: preliminary thoughts and conclusions