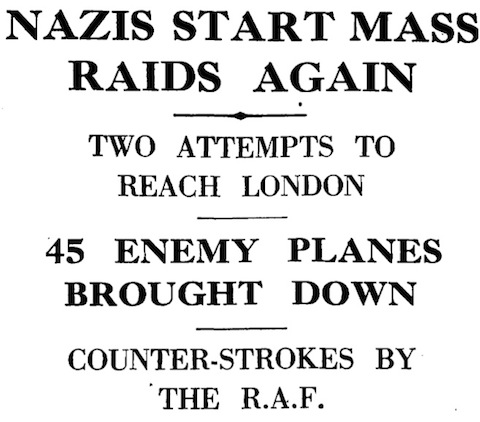

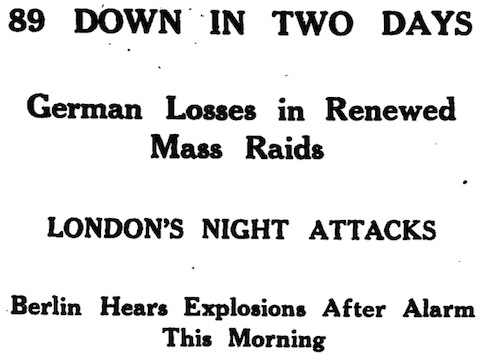

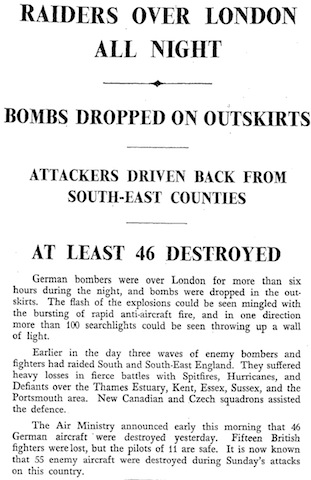

The daylight air battles over the south of England intensified yesterday, as these headlines from the Manchester Guardian (5) show. The RAF shot down 24 enemy aircraft while losing 12 of its own (4 of the pilots are safe). Churchill visited the south-east coast and saw some of the action. He was driven out from Dover to inspect the site of one crashed fighter:

An officer saluted as the Premier drove up. “Is it one of theirs or one of ours?” asked Mr Churchill, indicating the still-burning wreckage. “One of theirs, sir,” replied the officer. “Good,” exclaimed Mr. Churchill. “That’s another one off the list.”

Away from the headlines, The Times and the Manchester Guardian both report on two London events, one a Rotary luncheon and the other, I would guess, a background briefing by officials of the Air Ministry or perhaps the Ministry of Economic Warfare.

The luncheon speech was given by Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, an RFC veteran who had been in charge of Britain’s air defences in the 1920s and again in the 1930s, and who had joined up again upon the outbreak of war after a spell as Governor of Kenya. Yesterday he spoke on ‘factors in air superiority’, a very timely topic indeed. I’ll quote from the account in The Times (2) as it is fuller. Some of those factors are intangible: Brooke-Popham believed that Britain’s airmen were ‘fighting for the same things as Chaucer’s “veray parfit gentil knight” loved’ and it was this which enabled them to fight ‘against odds of four or five to one under all conditions’.

He would venture to prophesy that when historians had had time to catch up with events and write a history of the present war they would find that not least of the causes of Hitler’s defeat was our airman’s faith in the cause for which he fought.

Then there were technical factors, numbers (‘We had got to give numbers to the Germans for the present’), strategy and so on; Brooke-Popham had spent much of the last eleven months in Canada and South Africa working on the Empire Air Training Scheme and was of the opinion that ‘We were definitely ahead of the Germans in our training system’.

Brooke-Popham warned against the danger of ‘pressing for local defence by aeroplanes’: just because a particular city or town couldn’t see the RAF overhead doesn’t mean it isn’t being defended.

Aeroplanes proceeding to attack Oxford might be brought down in Sussex by a squadron stationed in Kent, and probably the best defence for Derby would be a bomber squadron in Norfolk which attacked aircraft factories at Dessau. They could not treat aeroplanes like toy butterflies which they whirled round their heads with a string.

Indeed, he fully supported Lord Trenchard’s views on ‘fighters and bombers’, as recently stated in a letter to The Times.

The fighter was strategically defensive, and to win a war they had got to be offensive. That was the job of the bomber. They had got to keep on hitting, and that made him wish sometimes that people would remember who was carrying out the offensive. They had got all sorts of Spitfire and Hurricane funds; why not have a Hampden or Stirling fund?

The chairman took the hint and duly opened a fund for the purchase of a bomber.

Brooke-Popham’s emphasis on the importance of the bomber is reaffirmed in the other story common to both papers today, the one quoting anonymous ‘Experts on Germany’s economic system’, as the Manchester Guardian described them (6). (I’ll quote the Guardian this time because it’s shorter and punchier!) Said system has been ‘seriously affected’ by RAF bombing.

The moral of the workers too is suffering from repeated raids, and — consolation of thousands who have spent disturbed nights in London — industrial workers in the Ruhr have been going to bed at 6 p.m. to get some sleep.

Some details are given of damage to Germany’s transport networks — railways as well as ports and canals — and to aircraft and synthetic oil production. This leads to what is, perhaps, the most heartening point:

The production of oil in Europe, excluding Russia, in 1940 is estimated to be 11,280,000 tons, and as Germany and the territories she now occupies consumed 20,000,000 in a peace-time year, 1938, its difficulty now that supplies from abroad have been cut off can be assessed.

So, all over by Christmas then?

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback: Airminded · Friday, 30 August 1940

Pingback: Airminded · Thursday, 14 November 1940