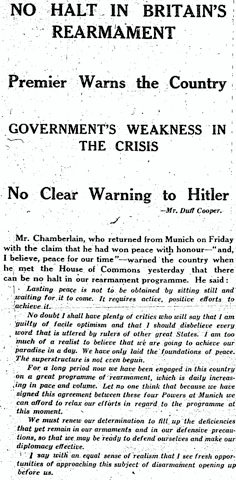

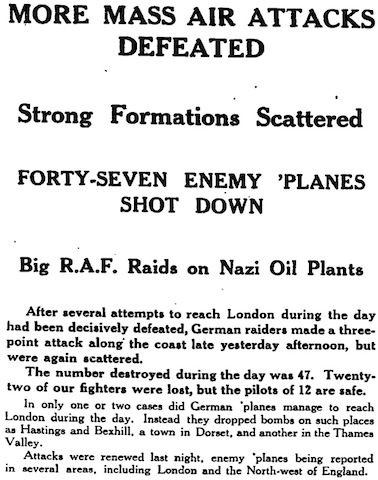

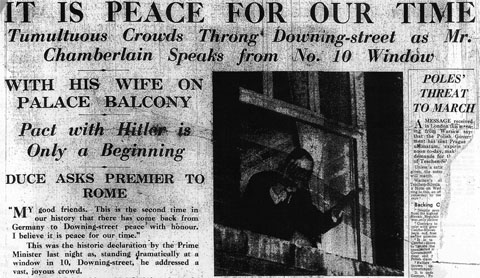

A few days ago, Chamberlain said Munich was ‘peace for our time’. Now he, in his speech in Parliament yesterday, he is saying that there can be no let-up in the pace of rearmament (Manchester Guardian, p. 11). In particular there is to be a ‘big increase’ in the RAF, especially for ‘the defence of London’ (Daily Mail, p. 11). Hoare, the Home Secretary, said in his speech that ‘on the whole the machinery of A.R.P. had worked well’, and it was mainly a matter of filling the gaps revealed by the crisis (Manchester Guardian, p. 6). Labour MPs were vocal in response to Chamberlain’s speech: the Daily Mail‘s parliamentary correspondent says (p. 10) they ‘wrecked his great hour’ and turned the occasion into ‘a shabby party fight’, and the leading article (p. 10) contrasts ‘The Government’s calm statement of the facts’ with ‘the frothy diatribes of the Socialists’. Duff Cooper’s resignation speech accused the Cabinet of being too timid to give a strong warning to Hitler, who he believed was more open to ‘the language of the mailed fist’ rather than Chamberlain’s approach of ‘sweet reasonableness’ (Daily Mail, p. 5).

Yet Labour did not get the numbers for a censure motion. They themselves are divided between pacifist and anti-fascists, as well as those who don’t want to give Chamberlain an excuse to call an election which he would presumably win, given the country’s mood (Manchester Guardian, p. 11). Anyway, there are only about 20 potential rebels on the government side of the House, the Churchillians and Harold Nicolson (National Labour), not enough to make any dent in Chamberlain’s majority. He has decided against going to the country for now; instead there will be a parliamentary vote tomorrow on Munich (Daily Mail, p. 11).

Reservists continue to be released back into civilian life — all naval reservists will be allowed to go back home, unless they are already at sea, although they’ll remain on the books for the time being (Daily Mail, p. 4). The Army will allow men who enlisted last week the option of being discharged, with a week’s pay and a gratuity. The few schoolchildren evacuated from London during the crisis are also returning home. A columnist in the Manchester Guardian (p. 8) writes of ‘The first waking moments that break a nightmare’:

Was it only a matter of hours ago that we saw a store counter labelled “A.R.P. Department” besieged by men and women? Had we actually seen young women there handling and comparing various gas masks as normally as they would examine new hats?

The Daily Mail has been out on the streets asking punters what they think of the idea of a bank holiday in honour of Chamberlain and peace, perhaps to be called Peace Day (p. 3). Unsurprisingly, everyone’s in favour of the idea! Irene Porter, a typist from Upton Park, would call it Chamberlain Day ‘as a mark of honour to the great man who prevented war’. But she’d rather it was between Christmas and Easter, rather than on 30 September when the Munich agreement was signed, ‘so that we could get a taste of spring’.

The letters columns are filled with reactions to Munich. Just to sample a few of the correspondents with the Manchester Guardian (p. 20): Gilbert Murray thinks the agreement unjust, comparing it with Versailles. But he hopes that the worldwide revulsion against war which motivated it can be used to secure a lasting peace. According to Francis Hirst, the former editor of the Economist, most Liberal voters would be grateful to Chamberlain for preventing ‘another ghastly Armageddon which would have brought ruin and desolation on countless homes’. But Tavistock implies that only a Conservative prime minister could have negotiated with Hitler; the Liberal and Labour leaders would have ‘involved millions of innocent people in destruction’ in misguided pursuit of collective security or simply because they hated him.

A cheerful ad from The Times (p. 19):

And an ominous story from the Manchester Guardian (p. 6)?

POLAND’S FEAR OF GERMANY

“Now More Than Ever Sheer Brute Force Will Dominate” — General’s Speech

NO RELYING ON OUTSIDE HELP

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

But is it too late to buy Hawker-Siddeley shares?

Nah. I’d definitely be going with Vickers-Supermarine.

In coming months production problems with the Spitfire would become so dire that the Air Ministry was seriously thinking about abandoning the project for home defence, and fobbing-off what was seen in some quarters as a lemon to overseas customers, so that at least some costs could be recouped.

Buy high, sell low. No, wait.

Yeah, but doesn’t that have more to do with production problems at Castle Bromwich? Vickers-built Spitfires have already been delivered to the service, after all.

Now, on the one hand, Nuffield’s organisation gets a great deal of criticism, just like all the other automotive consortiums that tried to build military aeroplanes during the period. On the other, Postain made the development costs of the Spitfire legendary mainly in the interest of overstating the costs of developing new types as opposed to modifying old ones.

All this said, once the first extruded aluminum spar became available (on the Westland Lysander?) the bizarre telescoping structure of the Spitfire’s wing was instantly industrially obsolete. In a perfect world, the Spitfire production run would have been run down in favour of new designs.

The question is, what exactly? The Whirlwind and Gloster F.9/37 are based on the Peregrine and Taurus respectively, both brand-new moderate displacement engine designs. Looking back on what their respective developers did with older, heavier engines like the Merlin and Hercules, I have to like the long term prospects of these newer, sleeker engines. But is now the time to be betting all your marbles on new developments?

Plus, twin-engine fighters are a somewhat debatable asset.

Wow Erik. We are riding into the deep badlands of Nerdvada. But as I can’t get enough, could you explain the bit about ‘bizarre telescoping structure’?

I was aware of the problems with Castle Bromwich, and associated difficulties with construction of the elliptical wing, but knew nothing about the spar.

The Yanks had been producing aluminium mainspars for years, non?

“Plus, twin-engine fighters are a somewhat debatable asset.” Yes, witness the Beaufighter. Or unless you get completely lucky with something out of left-field like the Mosquito.

Nothing bizarre about nested tube spars; it’s a very elegant way of producing a cantilever with properties which vary along the span. It’s easy to modify if loads change, unlike an extruded section. Attachments are simple, as is stress calculation; not forgetting that in those days a calculator was a lady winding handles on a typewriter-sized box of gears. There are other structural virtues too, should I mention double cell torsion boxes? – perhaps not in detail.

The downside is that they are more expensive to produce in quantity than are extruded spars, but at this stage we’re only going to produce a few Spitfires and it’s hardly worth the time and expense of setting up extrusion dies, especially when skilled toolmakers could be employed doing something more useful.

Lastly, a mantra I always keep handy (can’t vouch for the truth, but the punch line is magnificent). A Great Western Railway Chief Mechanical Engineer was asked by his directors why one of his locomotives cost 50% more to build than one built by the XYZ Railway. “Because one of mine can pull three of their buggers, backwards.”

Ian sounds like he knows what he’s talking about. My caveat would be that goes for normal aeronautical practice . The Spitfire was orderer as a “normal” plane, and designed as such. Looking at the life of the Bulldog or Fury, one might expect a 300 unit order to Weybridge in 1935, completing in the summer of 1939, and succeeded by a next generation plane, perhaps in 1942 or so.

The problem is that the situation had changed so much by 1938/9. Orders for the Spit had bloomed to a minimum of 1500 a/c, and the technical possibilities had been transformed as aircraft factories laid in machine tools and, especially, heat treatment facilities.

Extrusion wasn’t just a low cost, mass production technique in 1939; I think because of the fabrication limits that had existed previously, it offered designers considerable freedom to create new shapes and structures, notably in the Avro Lancaster.

Comparing the Spitfire to the Whirlwind, one might well make the case for the first time that the latter was preferrable because it was cheaper to make by the thousand. (as well as being expected to be faster, a cannon fighter, and so on.)

Of course, you’d be wrong, and were I a contemporary decision maker, I would still be a little diffident about the idea of a twin-engined day interceptor, as well as about taking a step backwards in engine displacement with the Pegasus and Taurus.

Alternatively, maybe Cyril Newall was in Petter’s pocket. ‘E wouldn’t have been the only air officer taking a bit on the side. (Butch Harris, Hap Arnold, Will Freeman, I’m looking at you.)

“The Spitfire was orderer as a “normal” plane, and designed as such. ”

I’m not sure about that. When the Spitfire was being ordered, the long lead-time items of 1939’s RAF (airfields, training) were already in place. Freeman’s memoirs might perhaps settle this. I’ve the official history of Vickers knocking around somewhere, too, but not to hand.

Oh by the way: “Ian sounds like he knows what he’s talking about.”

I am such a prat, and I apologise. What I meant to say was more like, “Ian knows what he’s talking about, whereas I run my mouth off all the time.”

On chronology, I just picked up a new book on the Spitfire by Leo McKinstry, which seems a cut above the usual enthusiast stuff. It reminds me that the design of the Spitfire was drawn up during the spring of 1935, when the only RAF expansion scheme in effect was the “deficiency programme” of the 1934 estimates. While that had been enough to trigger a stock market aviation boom, it only added a few fighter squadrons to the metropolitan air force.

I go with the argument advanced by John James in _The Paladins_, which is that the Air Staff drew up their expansion plan in 1934-35, and pretty much stuck to it, sometimes changing the letters they were calling it.

Pingback: Airminded · Post-blogging the Sudeten crisis: thoughts and conclusions

James wrote an interesting book, but he was talking about force levels and infrastructure. The aircraft production rates required to maintain a given force level vary dramatically between peace and war. 300 Spitfires would have maintained Fighter Command quite satisfactorily in peace time, but if war did break out during the Spitfire’s operational years, there really would be a need for a Castle Bromwich to produce 60 planes a week.

Scott’s _Vickers, A History_says that Supermarine got their first order for Spitfire (310) Spitfires ‘late in 1936’. I still maintain that at this stage, the Air Ministry were planning to be ready for a war (as opposed to a big airforce) in 1939, and thus ought to have taken note of the ease of manufacture. Evidence for this includes the massive expansion of flying training which went through in 1936.