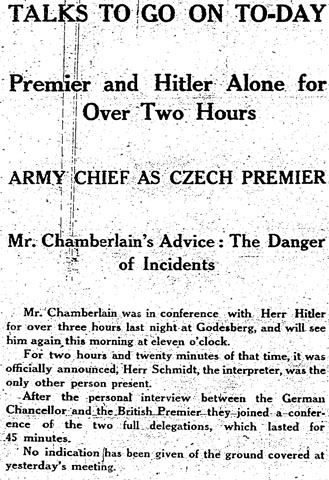

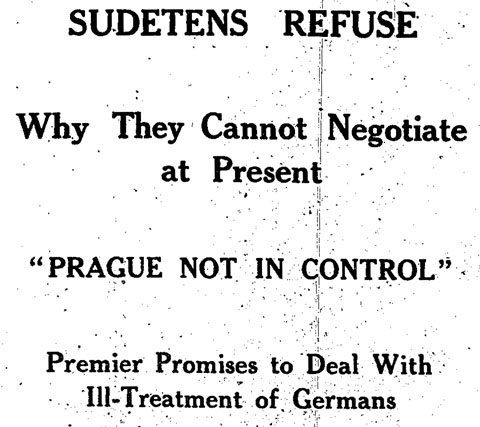

As these headlines from The Times (p. 12) report, it’s ‘a crucial day’, because Henlein is meeting with Hitler at Berchtesgaden to discuss the Czechoslovakian autonomy proposals; and everyone assumes that Hitler will have final say over whether the Sudetens will accept or reject them, as noted in the Manchester Guardian yesterday. Otherwise, there’s not much to report. As The Times says of the Runciman mission’s activities yesterday, ‘It was a time to wait and a time to keep silence — until the German answer should be known.’

This being a Friday, there’s a new issue of the weekly Spectator out. (Actually, I’m not sure that it was actually on the streets on Friday, but that’s what’s written on the masthead.) Its first leading article is devoted (p. 356) to the Sudeten crisis, and the first paragraph is not very reassuring:

THE FATE OF EUROPE

THERE can be no sane person in these islands who does not realise that within a space to be measured rather by weeks than by months — perhaps rather by days than by weeks — Great Britain may find herself at war. Alarming though that statement is it is not alarmist. It is implicit in every syllable of the references to the present international situation in Sir John Simon’s speech on Saturday. That speech reaffirmed, on the basis of deep deliberation between the Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary and the Chancellor of the Exchequer, what the Prime Minister had said, after deep deliberation by the Cabinet, five months before, and the Cabinet added its confirmation this week. If Germany resorts to force against Czechoslovakia, if France and Russia honour their obligations and go to Czechoslovakia’s aid, if in consequence France and Germany are at war, the arguments in favour of our joining France in arms may well seem irresistible. Nothing less than the fate of Europe is at stake.

But the dailies today seem more interested in the report of the British commission investigating the bombing of Alicante and Barcelona and elsewhere in Spain, which was foreshadowed on Wednesday. The conclusion was, as a leader in the Manchester Guardian put it (p. 8): ‘in general the rebel [Nationalist] Air Force is entirely indifferent to the fate of the civilian population, and in certain circumstances the civilian population is actually the object of the attack’. The report into these outrages are not linked by these papers to the Sudeten crisis in any way; it’s just stuff that was happening at the same time, and I mention it because (a) readers may have linked the two in their own minds, particularly since there’s also talk of war between Germany and Britain is and (b) it’s the sort of thing that interests me anyway. But sometimes similar bits of news were associated with the crisis, such as the following brief article, which was appended (p. 12) to a column from The Times‘s Berlin correspondent on the Berchtesgaden meeting and press attitudes to Czechoslovakia in Germany:

BERLIN A.R.P.

To-night and to-morrow night the authorities are testing the anti-aircraft defences of the Reich capital. Guns were mounted this morning on the roofs of public buildings, including the Reichstag, and manned by their crews. It is supposed that mock air raids will be staged during the night, but there is no black-out nor have residents been instructed to get into the cellars when the sirens sound.

There’s not even a horizontal divider between the two stories, so they are probably actually one article.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Actually, I’m not sure that it was actually on the streets on Friday, but that’s what’s written on the masthead.

The date of the New Yorker in my mailbox never seems to have any connection to the actual date I get it. I wonder if the web will make it easier or harder for future historians to work out what people knew on any particular day.

Actually I think I could have squeezed another actually into that sentence!

Yes, I was thinking of the Economist when I wrote that. The print edition has Saturday’s date on it, which, as it happens, is when it becomes available in Australia (if your newsagent is on the ball, at least). But it’s on the streets in London on Thursday or Friday (can’t remember which). Online it’s available on Thursday. Presumably the Saturday is an historical relic?

The news content of this issue of the Spectator seems to correlate best with what was being said on the dailies on 1 September, i.e. the Thursday. That doesn’t help pin down when it was actually read by the public very much, though.

Pingback: Airminded · Monday, 5 September 1938