My second (and last) day in York. Luckily, since I’d seen the two major attractions (for me) on my first day there, I was free to wander around with only a vague plan in mind. And there was a lot to see. One of the great things about York, I found, was the way in which nearly all periods of history are represented by some substantial survival or site, all within easy walking distance. It’s like a slice through Britain’s/England’s/Northumbria’s etc past. So, to illustrate this, I’ll write this post chronologically by site (rather than chronologically by time of day visted!) With the exception of the above: that’s Clifford’s Tower, which should come in the middle somewhere, but it’s too pretty a picture not to put up front.

I did say ‘nearly all’ — there doesn’t appear to be much from the prehistoric period. So I’ll start with the Romans, who called the city Eboracum. It was the centre of Roman administration for the north of Britain, and the site of a legionary fortress. This is the Multangular Tower, at the south-west corner of the fortress. The lower courses of stone (about 6 foot high) is Roman, I think, the rest being medieval. It’s from either the early 3rd or the early 4th century, depending upon which piece of the internet you believe. Both dates seem plausible, due to Eboracum’s strong imperial connections. Two emperors died here: Septimius Severus in 211, and Constantius Chlorus in 306 (the local legionaries were the first to acclaim his son Constantine as emperor).

The other side of the tower — the ground is a bit lower here so more Roman stonework is visible. I’m not sure what the story with the coffins is! Not shown: all the grey squirrels that were running around.

Also Roman: a column which was unearthed in 1969 from beneath York Minster, besides which it now stands. In fact, the Minster sits above the site of the legionary headquarters. This column was part of that building, which was obviously pretty grand, and there are further remnants in the cathedral’s undercroft.

I don’t have any photos to represent the next phase of York’s existence, as Anglo-Saxon Eoforwic, capital of the kingdom of Northumbria (I seem to have missed the Anglian Tower, which may date to this time). In the 8th century, Eoforwic produced the great scholar Alcuin, advisor to Charlemagne, a sign that it wasn’t doing too badly without the Romans.

I don’t have any photos for the next phase, either, but that’s only because no photography is permitted inside the JORVIK Viking Centre! From the late 9th century, York was the capital of a small Danish kingdom, part of the Danelaw. Its new rulers called it Jórvík. Whatever the name, the city flourished, and by the turn of the millennium was second in size only to London. Coming forward nearly another millennium, archaeologists digging on the site of a planned shopping centre found a huge number of remarkably well-preserved artefacts from the Viking period — parts of timber buildings, clothing, shoes, as well as the more usual bits of pottery. Now, I would never use the word ‘tacky’ to describe the JORVIK Viking Centre itself, so get that right out of your mind when I tell you that the first part of the JORVIK experience is a simulated time capsule ride through reconstructed (sights, sounds, and smells) Viking streets, with animatronic mannequins talking about their daily lives (as Vikings, of course, not as mannequins). I’m sure kids love it, and I can’t say I didn’t enjoy it myself, but I found the somewhat more traditional museum beyond more interesting. Here there were some of the actual Viking objects dug up from this very site. There were also museum staff dressed in period gear interacting with the visitors, which I thought worked very well. All in all, I’d have preferred more of the museum-y bit than the theme park ride-y bit, but I can’t argue with success: it’s had 14 million visitors in two decades, and there are now a couple of subsidiary ‘attractions’, or whatever they are called.

York Minster, which I’ve already talked about. Early 13th century. The steeple in the foreground is York St Mary’s (an ex-church, also early 13th century), and the church in between is, I think, All Saints Pavement (late 15th century).

Clifford’s Tower, as seen at the top of the post, a nice example of a motte-and-bailey castle — here’s a close-up. It was built in the late 13th century. In 1190, York’s Jews huddled inside an earlier, wooden tower on this spot, besieged by the other townsfolk. The tower caught fire and most of the Jews died in the flames; those who did survive were murdered by the besiegers. In all, one hundred and fifty were killed. To add to the bloody history, the tower gets its name from Roger de Clifford, a rebellious baron who took part in the Battle of Boroughbridge in 1322. The victorious but unmerciful Edward II had him hanged him from the top of the tower.

It’s far more peaceful to visit today, I’m happy to say. And there are great views of York from the top (the photo of York Minster above is taken from the battlements). This is a view looking down inside the keep. It’s probably not very clear in these pictures, but the plan of the structure is an unusual quatrefoil shape, apparently unique in England.

Bootham Bar which, along with Mickelgate Bar, is one of the four entrances into the medieval city. It mainly dates to the 14th century, though some of it is as early as the 11th century, and is near the site of one of the main gates to the Roman fortress.

York’s city walls, which I’ve already talked about, and which are mostly 14th century. I loved these; I think Melbourne should get some. Can you believe that in the 19th century, York’s businessmen wanted to pull them down, because they hampered the transport of goods in and out of the city? Well, I suppose it’s understandable — but I’m glad they were unsuccessful.

The Merchant Adventurers’ Hall, built in the mid-14th century. Not only that, but it has been run by the same guild for all that time.

As the name suggests, they were traders, with northern Europe and the Baltic mainly. They have a fun little trading game set up underneath a staircase, which you can play online. I just made a profit of £367 in 6 months from an outlay of only £50 — clearly I’ve missed my calling!

They also had, for a long time, oversight over other merchants in York — regulating weights and measures, for example. Above is the Great Hall, where many of their transactions would have been carried out.

One of the 16th century governors of the Merchant Adventurers, I think — can’t make out his name.

The Undercroft, which served as a hospital. The guild actually began as a charitable organisation. Beyond is the Chapel, which is still used for religious services.

A heraldic device of the Company of Merchant Adventurers from the mid-18th century. Today, they are still involved in charitable and business activities, and in recent times have revived their old tradition of putting on mystery plays.

The centre of York is filled with all these wonderful little medieval streets. This is the best known, Shambles — originally where all the butchers were. Bits of offals and fat and so on were just thrown into the gutter in the middle of the street, a practice that seems to have been discontinued at some point in the last five hundred years.

At points the buildings in Shambles lean over to almost kiss each other.

The Coffee Yard, one of York’s narrow snickelways, which connect the bigger streets (Shambles has five snickelways coming off it). Many are medieval, though this one is 18th century as far as I can tell. It’s the longest one in York (67 metres), but it’s also one of the most boringly named, when set against Mad Alice Lane, Hornpot Lane Nether or Three Cranes Lane.

This photo, and in fact all of the rest of the photos in this post, were taken at York Castle Museum. The name is a bit misleading, since York Castle itself is long gone, except for Clifford’s Tower, which is nearby but not actually part of the museum. In the 18th century, several prisons and an assizes court were built on the site, and the prisons later became the museum. Here’s a graffito scratched by one of the prisoners in 1831.

I thought the Museum was excellent. Its focus is on the history of everyday life, which it portrays by recreating rooms and even entire streets from different periods, with shops, vehicles, light and sound effects (eg rain, day/night) and actors playing shopkeepers or policemen. To this extent it’s not dissimilar to YORVIK, except there are fewer mannequins here. (All to the good as far as I’m concerned.) The explanations given of the various displays were quite sophisticated: for example, the argument was presented that new domestic cleaning technologies (vacuum cleaners, electric washing machines, and so on) didn’t free up housewives’ time, as advertised, but merely set new standards of cleanliness — the net result being they were just as run off their feet as before. I’m sure this was food for thought for those who bothered to read the labels! (Not many, unfortunately.) Another thing I liked was the way the bicentenary of the abolition of slavery was marked. Instead of having a separate exhibition, what the curators did instead was to single out an object in each of their period rooms (e.g Georgian, Tudor) and explain its relation to the Atlantic triangular trade. Maybe this was just because they didn’t have the money or the space for a full-size exhibition, but it struck me as a clever way of showing how slavery wormed its way into daily life, even when there were no slaves around. Well done that museum.

I must complain about one thing, though. There was a display boasting about York’s great chocolate-making tradition, and in particular how it is (was) the home of Terry’s. But not once did I see a single chocolate orange in any shop in York. And I looked, believe me. They’re much easier to find in random 7-Elevens here in Melbourne. Shame, York, Shame!

Above is a candle maker on the Victorian street. I have no idea how accurate it is, but it looks grimy enough.

A wall covered with posters for plays, also from the Victorian street.

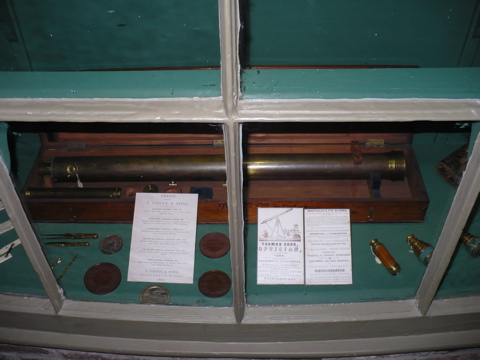

Another Victorian scene, a faux shop window for T. Cooke & Sons, opticians. This was a real firm, who exported telescopes all around the world. Back when I was in astrophysics, there was a beautiful old Cooke refractor on top of the physics building. I think it came to the department from the Melbourne Observatory during the Second World War. They were surprised, five decades later, to find out that we had it, as they’d lost track of where it had gone!

From the Edwardian street, two cars for hire.

I apologise for the poor quality of this one but as it’s airminded, I had to include it. It’s a toy Wright flyer, probably 1908 or so. It’s obviously not airworthy, so I suppose it was used just as seen here — suspend it from the ceiling, wind the key, and watch the propeller push it around in circles.

A Meccano aeroplane from 1934. It looks a lot like the paper aeroplane published in the Daily Mail that same year. I had a look to see if it was based on a real aeroplane, but couldn’t find anything. It would be an experimental RAF fighter, presumably, or just a research aircraft. Any ideas?

Outside the museum, a 25-pounder, my favourite artillery piece of the 20th century. (Don’t look at me like that.) There’s a good (even though it has mannequins) section on York and war inside — I’ll write a post on another item drawn from that in due course.

Now that we’ve reached the mid-20th century, I’ll stop. It’s almost not history after that, anyway. (Though it’s a pity I didn’t find out about the York Cold War Bunker until yesterday!) I must admit to not knowing much about York beforehand. I knew something of its history, of course, but not how much there is to see there today. And as it was, I (inevitably) missed out on a goodly number of other sights (the Richard III Museum is supposed to be good too). But I’d probably never have thought to go there if it wasn’t for Gavin’s and war+hog’s advice, so thanks guys!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback: Airminded · Black-Out

Brett,

I’ve been reading your site for some time now, with great interest. I’m not an academic, but definitely qualify as “airminded”. Your visit to York finally pushed me into commenting, as I grew up in York in the 50’s. Anyway, comments;- The meccano aircraft (don’t remember seeing it, but it’s a long time since I last visited the Castle Museum) looks like a cross between a DH 77 Interceptor and a DH 53 Humming Bird. The “Nuclear Bunker” is actually the former Royal Observer Corps 20 group headquarters. I was in the ROC, bur left to start an apprenticeship at De Havillands just as the new HQ became operational. Last time I was in York, some 3 years back, the old brick HQ near the Knavesmire, where we plotted real aircraft, was still there. Good luck with your endeavours!

Always nice to meet a lurker, Ian! Yes, you’re right — it is quite similar to the DH 77 and DH 53. They’re both from the 1920s — I think I was looking for something from 1934, something up-to-date, which might be why I didn’t consider them. But I guess those wing braces are a bit old-fashioned for 1934.

Interesting that you were in the ROC. What was it’s role to be in a nuclear war? Was it just recording and reporting the nukes going off? Or were you planning for a conventional attack?

When I joined the ROC (1958) it was still pretty much an RAF auxiliary, officers with handlebar moustaches and all. We spotted, reported and plotted aircraft in a very similar manner to our WW2 predecessors, though things had been simplified and speeded up, with special procedures for fast low flying aircraft (Rats). The nuclear reporting role was just being introduced, the observer posts were given “bunkers”, a small underground room with bunks and stores, airlock and reinforced tunnel to the surface, a nuclear burst recorder (a souped-up pinhole camera), a pressure recorder to measure the blast strength, a Geiger counter to measure the fallout, and individual dosimeters (we were rather cynical about these).

The operating theory was that there would be sufficient political warning for the observers to man their posts, they would wait for the noise to stop, surface, extract the recording paper from their recorders, read off the bearing and altitude of the burst and the peak overpressure. This would then be phoned in to Group HQ where we would plot the (hopefully several) bearings, and get the position of the detonation. Then, using the reported overpressures, plus sets of tables and nomograms we woud evaluate the bomb power and report back to…..anyone still alive. After that the posts would report radiation levels at regular intervals until…

Pingback: Airminded · Chesters

Thanks for that, Ian. I can’t imagine what it would have been like to sit there in a bunker recording the death of civilisation like that, but your description is very sobering.

Pingback: Airminded · When two tribes go to war

Brett, a very interesting site, we did not get to York when visiting the UK but it has given me some ideas for future visits. The Meccano aieroplane dates from the 1940s when they and the meccano constructor cars were made. In essence they are made up of a number of parts from which you can construct many different types of aircraft eg biplanes, single wing fighters, seaplanes etc. The aircraft pictured is most likely from a no1 aeroconstructor set. They have very good manuals to guide the keen meccano users to make an aircraft of their choice.

I make my own replicas of these aircraft out of tinplate and have some pictured on my flickr site.

Cheers Gary

Thanks for that information, Gary! So it doesn’t necessarily represent any particular aircraft type of the period.

Pingback: Airminded · From Cardiff to Conwy