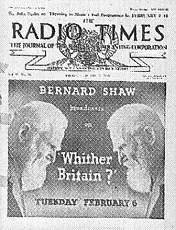

Part of a BBC broadcast by George Bernard Shaw, entitled ‘Whither Britain?’, 6 February 1934:

Are we to be exterminated by fleets of bombing aeroplanes which will smash our water mains, cut our electric cables, turn our gas supplies into flame-throwers, and bathe us and our babies in liquid-mustard gas from which no masks can save us? Well, if we are it will serve us right, for it will be our own doing. But let us keep our heads. It may not work out in that way. What will London do when it finds itself approached by a crowd of aeroplanes capable of destroying it in half-an-hour? London will surrender. White flags and wireless messages ‘Don’t drop your bombs; we give in’ will fill the air. But our own squadrons will have already started to make the enemies’ capitals surrender. From Paris to Moscow, from Stockholm to Rome, the white flags will go up in every city.1

Shaw accepts a key tenet of the knock-out blow here: that it is awesomely destructive. So much so that the immediate impulse would be to surrender. But he also accepts another tenet: that it is extremely fast. He uses this to paint an absurd picture of the capitals of Europe therefore surrendering simultaneously. In effect, the knock-out blow is so powerful that it is pointless to attempt it. Flight (the more moderate of the two British aviation weeklies) quoted Shaw because he illustrated its editorial position, that the bombing of civilians as such would not happen, just as dum-dum bullets were not used in the late war, and prisoners were not tortured to death: ‘absolutely unrestrained warfare is unthinkable. A line must be drawn somewhere’.2 It was therefore sensible to ban bombing of civilians (as opposed to legitimate military targets), but not to ban bombers altogether, as some were trying to get the Disarmament Conference at Geneva to do. Even worse would be to ban fighters, because they were a sure defence against airliners converted into bombers.

I didn’t know that GBS had spoken on the wireless about the threat of bombing. It was only in looking through another, printed, source that I came across this excerpt. As it happens, Shaw’s broadcast (part of a series of twelve; another speaker was H. G. Wells) has been preserved3 and can be purchased, or even listened to for free (if you are in the British Library).

But more generally, I wonder what the best way to find information about the contents of early radio broadcasts is? Infax is great, but very incomplete for my period, has only very basic search capabilities, and limited information as to content. Ditto for the British Library Sound Archive. I think the best sources are likely to be the Radio Times and The Listener. The former isn’t available here (before 1959, anyway); I’ve never seen a copy and I don’t even know how detailed its information would be. But I see that the State Library carries The Listener — apparently more highbrow and so probably a better bet anyway — from September 1937 onwards, so that’s something.

Image source: TV & Radio Bits.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

If you were being charitable, you could say this prefigures mutually-assured destruction. If you were being less charitable, you could say this is just one of many examples of GBS being more intelligent than he was smart.

The BBC’s own database is pretty comprehensive – it certainly goes back to 1940 – but that’s for internal use only, as far as I know. You might also try the BBC written archive at Reading when you come over to Blighty. They bring you tea and everything, and there’s a nice ‘Y Service’ feel to the place, since it’s next to the BBC Monitoring Unit.

Yeah, I’d try out the WAC – their holdings can be variable, but they are extremely helpful (helped me find the two times Haig spoke on the wireless, even if there’s no recording of him doing so). And if you ask really nicely, and what they’ve got isn’t big, they might even copy it for you and send it to you, although this does mean you miss out on the tea and biscuits.

I’ve also enjoyed the tea and biccies at the BBCs WAC. But do they still have the same absurdly inflexible opening hours that they used to? I seem to recall them being open for about 10 minutes a week while I was there (OK, perhaps a slight exaggeration. But not much.)

Thanks for the tips — I hadn’t thought of actually going to the BBC! But would it be a useful exercise to turn up without having specific programmes or at least personalities in mind? My thinking was that sifting through programme schedules (which I’m sure the BBC would have, but would be more accessible in the Radio Times/The Listener would let me identify potentially interesting broadcasts, and maybe have previews or reviews of some them. If I needed more information, the BBC would be the next stop.

Of course, it’s not like I actually need MORE information … I’m drowning in photocopies and pdfs as it is. But I would like it …

I deal with some of the same sources you’re using here. With a little skillful typing, and the insertion of a few “plus” signs, it’s actually possible to hack a search URL into the Sound Archive: “Whither Britain?“

Thanks for the tip!