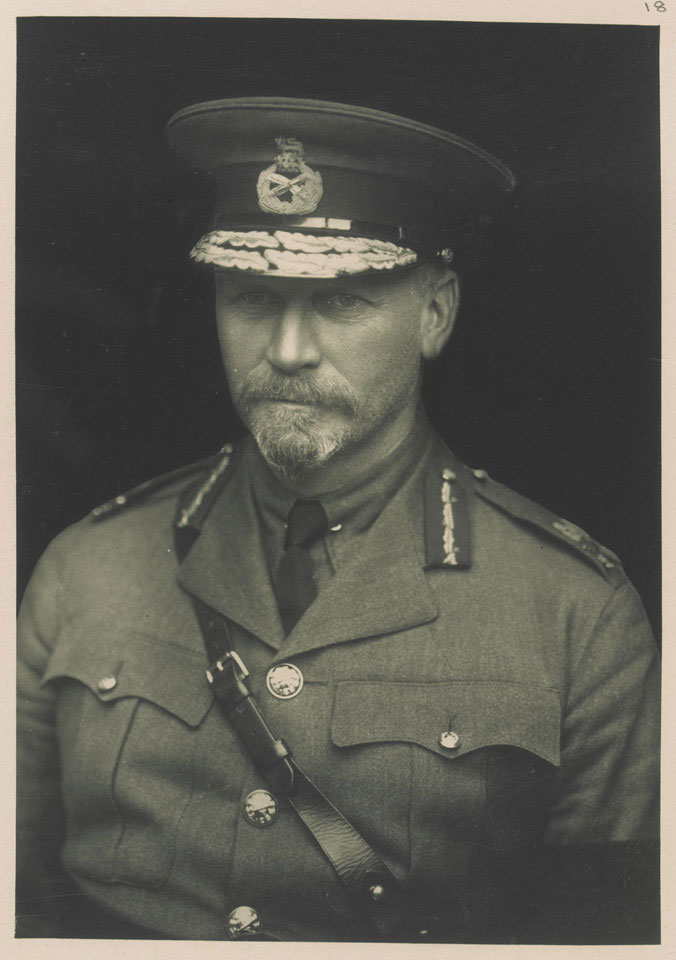

Like many people – out of the sort of people who know these sorts of things, that is – I knew of Jan Smuts’ key role in the origins of both the RAF and the Air Ministry. It was the so-called ‘Smuts report‘ to the War Cabinet, in August 1917, which set the whole process rolling and, after some twists and turns along the way, led to the formation of the Air Ministry in January 1918 and then the formation of the RAF the following April.1

This has always seemed slightly weird, because not only was Smuts an outsider, as the South African defence minister, but also a former enemy of the British Empire: he’d been a Boer commando officer during the South African War. But he was an astute, original thinker, and, just as importantly as far as Lloyd George was concerned, a clean pair of hands, who had not been sullied by involvement with the Western Front strategy. Thus, with the Gothas raiding London in June and July 1917, the press and parliament in uproar, and a political and military solution urgently required, Lloyd George turned to Smuts for help, appointing him to a committee consisting of the both of them.2

Now, I also knew that the Smuts report wasn’t the only, or even the first, report to come out of this committee. It was preceded in July by a more pressing inquiry into London’s defences. This report was also quite consequential, if not quite as consequential, since it led directly to the formation in August of London Air Defence Area (LADA), which integrated fighters, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and observation posts into the one command, a successful arrangement which was reproduced in the interwar period and eventually evolved into Fighter Command. So that’s two really important appearances by Smuts in the origins of British airpower. Not bad for somebody who’d only been in the country for less than six months.

What I didn’t know until combing through the War Cabinet records for 1917, however, was just how much Smuts was called upon as an aviation troubleshooter. Almost every other meeting, it seemed, he was being appointed to chair yet another committee or solve another pressing problem relating to air raids or air policy or air production.

Here’s a list of his aviation-related committees, with his role and date of authorisation:

- 11 July 1917: member, Air Organisation and Home Defence against Air Raids Committee3

- 24 August 1917: chair, Air Organisation Committee

- 23 September 1917: chair, Aerial Operations Committee (War Priorities Committee from 8 October 1917)

- 1 October 1917: chair, Air Raids Committee

- 15 October 1917: chair, Air Policy Committee

Just what all distinguished all these very similar-sounding committees from each other is not entirely clear now, and probably wasn’t either then. But a few things can be said, even without drilling into their papers. The Air Organisation Committee was devoted to laying the groundwork for the unification of the RFC and RNAS into the RAF, including preparing the legislation required for setting up a whole new service. The Aerial Operations Committee was tasked with adjudicating the air production needs between the Army and the Navy (later expanding into all munitions). The Air Raids Committee was initially set up to look into anti-aircraft guns and ammunition for London, but almost instantly was given the question of bombing Germany. And the Air Policy Committee’s remit was to advise the War Cabinet on all air policy questions.

Nor was this all, because Smuts was also detailed by the War Cabinet for several other one-off reports or investigations on air matters:

- 14 August 1917: investigate carrying out reprisal raids in conjunction with the French

- 5 September 1917: investigate previous two nights’ raids, along with the questions of air raid shelters and reprisal raids

- 30 November 1917: sent to Coventry to speak to striking aircraft factory workers

- 6 December 1917: prepare public statement on previous night’s raid

Even well into 1918, Smuts ‘continued to deal with air matters’ on behalf of the War Cabinet, according to Peter Dye.4 This is starting to sound obsessive!5 Surely the whole point of having an air minister at all was to ‘deal with air matters’?

Part of the issue here was probably that the actual air minister, since November 1917, was Lord Rothermere, whose time in the post was marked by chaos, conflict and confusion (and that’s just inside the Air Ministry). So it might well have been useful to be able to get a second opinion on what was still a very new political and military arena. But then again, why not just go ahead and make Smuts the actual air minister in the first place, or even the second?6 As far as I know, he wasn’t considered for the role. Perhaps there was some constitutional issue or perhaps he was just too valuable as a political pinch-hitter (he was also vice-chair of the high-level War Policy Committee, for example).

Still, I reckon Smuts’ deep involvement in so many aspects of air policy in this crucial year is enough to warrant considering him the first, or rather the zeroth, air minister.

Image source: National Army Museum.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

- The best account of this is in Christopher Luck, ‘The Smuts Report: interpreting and misinterpreting the promise of air power’, in Changing War: The British Army, the Hundred Days Campaign and The Birth of the Royal Air Force, 1918, ed. Gary Sheffield and Peter Gray (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 149–170. [↩]

- Lloyd George was nominally the chair of the committee, but did not actually take part in its work, hence Smuts gets the credit. [↩]

- Or Committee on Air Organisation and Home Defence against Air Raids Committee, Prime Minister’s Committee on Air Organisation and Home Defence against Air Raids Committee, etc. [↩]

- Peter Dye, The Birth of British Airpower: Hugh Trenchard, World War I, and the Royal Air Force (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2024), 153. [↩]

- I did consider calling this post ‘Smuts, Smuts, Smuts, that’s all they think about‘. [↩]

- Though Rothermere’s replacement, Sir William Weir, turned out okay. [↩]