‘In the future, every historian will be relevant for 15 minutes’, as somebody once said. Here’s my 15 minutes, an interview with journalist Connor Echols for Responsible Statecraft on the parallels between the 1913 phantom airship panic and the 2023 spy balloon panic. As I’ve been busy with other things and have had to watch take after hot take flash by (most interestingly from my point of view was Jeff Sparrow in the Guardian invoking another interest of mine, balloon riots), I appreciated the opportunity to think about what I do think (if that makes sense!)

And what are the parallels? As they say, read the whole thing. But if I may be permitted to quote myself:

There are some big differences. The balloons shot down by the US military in 2023 are in fact real, unlike the phantom airships. At least one of them was acknowledged by the Chinese government, though claimed to be civilian and harmless; in 1913 the German government, credibly, denied all knowledge of the phantom airships. Finally, the phantom airships were a mass phenomenon, seen and reported by ordinary people; the spy balloons are tracked on radar and seen only by military pilots. As far as I know, there hasn’t been a spate of people reporting phantom balloons this time around.

Airships, especially Zeppelins, were highly advanced technology in 1913 – so advanced that Britain, the closest thing to a superpower that then existed, could not build a credible airship fleet of its own. In 2023, as many commentators have noted, balloons are hardly cutting edge; in fact, they are the oldest form of human flight, 240 years old this year. And for surveillance they seem completely outclassed by satellites. There are some advantages balloons possess in terms of loiter ability, and they are more steerable than they used to be, especially at stratospheric heights. But I don’t think it can be argued that anxiety about balloon espionage has been building over the last few years. If anything, I would have expected a drone panic instead.

But there are some common features. There is the panic over a foreign threat being whipped up by the press. This taps into existing anxieties of unforeseen dangers which can upset the status quo, perhaps particularly worrying for a dominant power like Britain before the First World War or the United States today. In domestic political terms, these panics are useful for those who want to argue for defensive and offensive action, but also, and maybe mostly, who want to attack the government of the day.

Stepping back a little, it seems like the particular form of the panic doesn’t matter too much, whether it’s airships or balloons. It’s the sky itself which is the threat vector. It’s above us at all times. We can’t escape it, we can’t keep it away. And that’s usually not a problem. But it’s always there as a potential way for enemies to reach us, and when we are anxious about outsiders the sky can become a screen to project those anxieties onto.

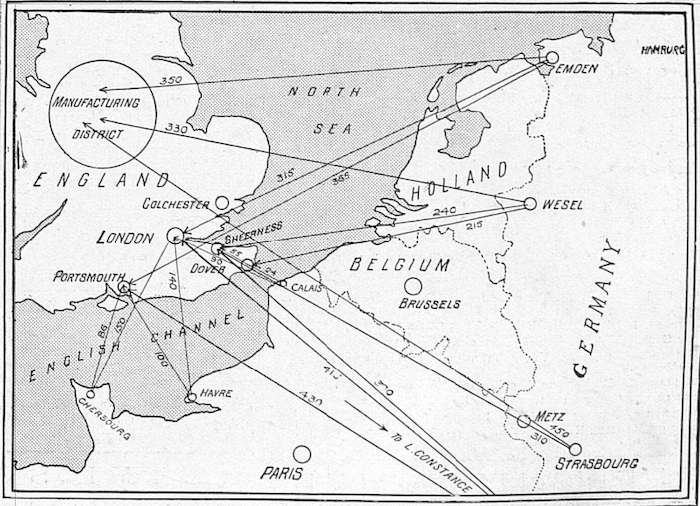

Images source: Sphere, 1 March 1913, 223.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.