After Glasgow, York. This was a place we had both previously visited and loved, but not for well over a decade and not together. So we were curious to see if we would enjoy it as much now. Folly? Yes, but that’s not important right now.

It did in fact take us a little while to find our way back into loving York again, as it all felt a bit more keen to extract the tourist pound than we’d remembered. (It probably didn’t help that we arrived on a bank holiday, along with about a million day-trippers.) But ultimately it was impossible to resist so much history piled on history. Here’s the 13th-15th century York Minster looming over (I guess) 18th/19th/early 20th century residential buildings, as seen from the 13th-14th century city walls.

This was originally in the Minster, now in the Yorkshire Museum. It was part of a 14th century shrine around the tomb of St William, which was destroyed during the English Reformation and buried nearby. The museum suggests it could be meant to be a pilgrim who had suffered a stroke.

The fabulous 8th century York Helmet, one of the most spectacular surviving examples of Anglo-Saxon craft, found in 1982 during excavations for a new shopping centre. It’s engraved with the name Oshere, possibly a member of the Northumbrian royal family. (I know what you’re thinking, but no, no relation to Oshere of Hwicce!)

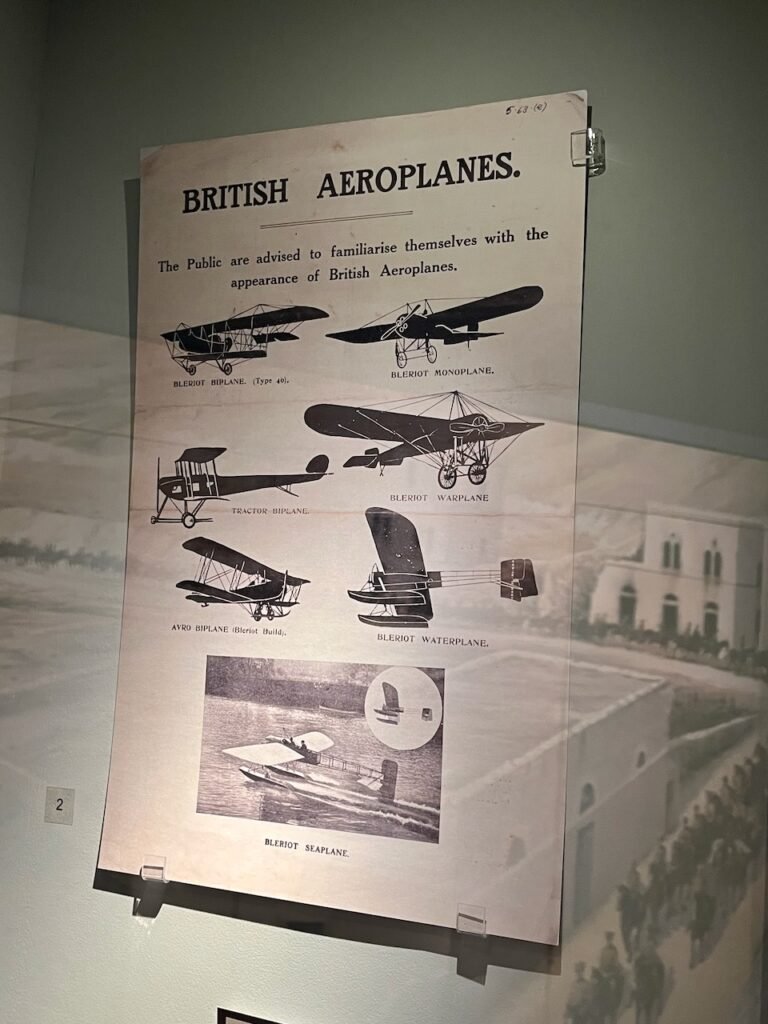

This was a fascinating find in York Castle Museum: an early British aircraft recognition poster, one which I’d never seen before. (As opposed to this one, which is everywhere.) Unfortunately it has little identifying internal contextual information, the placard is singularly unhelpful (‘Poster “British Aeroplanes”, around 1914-18’) and I can’t find a record for the poster in the Yorkshire Archives, even given the reference number ‘5.63.(e)’. But it is clearly very early, as those are all prewar types (the Blériot XL flew in 1913, for example). It must be from 1914, well before any actual air raids on Britain, and I’m certain it was made during/because of the Zeppelin base scare between August and October, to help nervous citizens correctly identify what they might be seeing in the skies. But I’d love to know when, where, who and why more precisely!

For a change in scenery (and century), we took a bus out to Castle Howard, which is not actually a castle but a very stately home. Practically a palace, in fact. It took the entire 18th century to build, plus another decade or so beyond that.

The building at the top of the post is the Temple of the Four Winds, 1724–26, is one of a number of follies scattered throughout the vast grounds. (Actually, as it’s described as a ‘garden house’ it might be too useful to be a folly proper, but it was folly enough for me.) Which are lovely, but as it was a wet and quite blustery day we didn’t get to enjoy them as much as we would have liked.

But there was plenty to look at inside. Here’s one of many classical statues scattered about the place – a 2nd century Antoninus Pius, I think. Alright for some! This is not exactly an original observation, but walking through Castle Howard really brought home the immense amount of capital tied up in building and then running and maintaining places like this – which, of course, had to be extracted from other places, very much not like this. It’s no wonder nearly every heritage site we went to was trying to engage in a discussion about slavery, race, and colonialism. (I mean, not Castle Howard, obviously.)

And onto Liverpool. Neither of us had been here before, so it was all new. Again, when we’d got our heads around the place, we really enjoyed it. Thanks to the grand architecture, especially along the Mersey – above is the Royal Liver Building (1911), complete with mythical liver birds – it felt like a big city in a way that Glasgow didn’t, even though it’s actually a bit smaller in population terms (860,000 vs 960,000).

On local boy Alan Allport’s recommendation, we visited the Western Approaches Museum (handily located across the road from our hotel), which is basically the command bunker from where the North Atlantic convoys were run during the Second World War, which sits under a massive neo-classical office building. This was really fascinating. Above is the operations board where the status of the various convoys and known U-boats was shown, all managed by a small army of Wrens. (The Museum fittingly has an excellent exhibit on the WRNS.)

I love this kind of re-created heritage space, where it almost feels like the historical actors have just stepped out for a few minutes and might return at any moment. (The Cabinet War Rooms is another great example of this, or was 17 years ago anyway.) Above is the office of Admiral Max Horton, Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches, 1942–45.

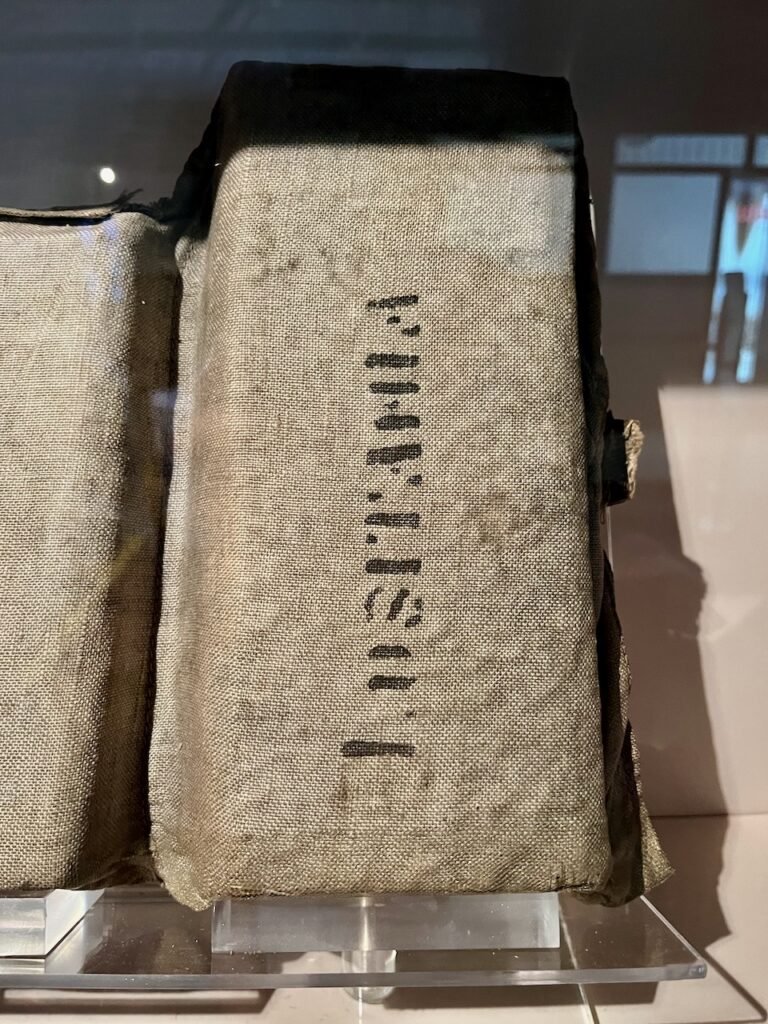

Same weapon, different war: one of the Lusitania‘s life jackets, found by an Irish fisherman. This is part of the excellent Lusitania exhibition in the Merseyside Maritime Museum, which also has an also excellent Titanic exhibition. (The 1910s was not a good decade for liners homeported in Liverpool.)

Back in the Western Approaches Museum, there were a few “gran and grandad’s war” (or rather great-gran and great-grandad, now)-type displays, obviously aimed at school groups: very hands-on exhibits on the Blitz, rationing and so on.

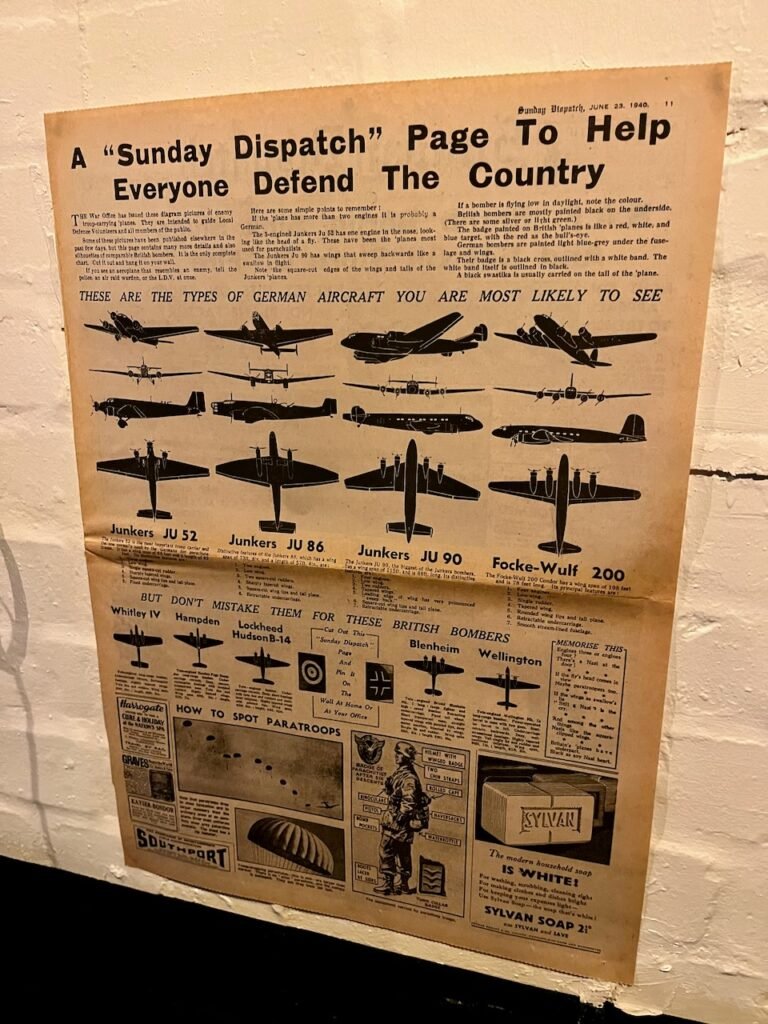

This display caught my eye (and compare it to the 1914 aircraft identification poster above): a page from the Sunday Dispatch, 23 June 1940, intended ‘to help everyone defend the country’ by showing ‘the types of German aircraft you are most likely to see’. Note that not only did virtually none of these ever appear in British skies, they’re all troop transports, not bombers – for this was the day of the parashot!

To prove that Liverpool isn’t all death and destruction, here’s the interior of Liverpool Cathedral, a typically massive and yet wonderfully light design by Giles Gilbert Scott, who of course is also responsible for Battersea Power Station (and the red phone box, among other things).

Humblebrag: we managed to avoid the Beatles almost entirely! (Apart from a cute Fab Four-themed café we went to a couple of times.)

Next stops: Conwy and Bath.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.