NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066, page 871 is a copy of an anonymous letter sent to the Minister of Defence in Melbourne in reference to reports ‘in the press on Saturday that two aeroplanes were seen flying over Nyang’ — likely either the Argus or the Age. Probably the latter, since it added a report from the Central Flying School at Laverton (well, Point Cook) saying it wasn’t one of theirs, and the letter writer says ‘This may only have been a trial flight by our own men, and again it may not’.

But the aeroplanes are not the real point here; they’re not even mentioned again. Instead the writer informs the Minister of ‘the fact that a late Officer in the German Army, by the name of Schefferdecker (Farmer) lives either at Cow Plains or Murrayville — a few stations further on’ from Nyang. He had only arrived in Australia a few months before the war. The writer wants the Minister to see ‘that the matter is thoroughly investigated’ — though what, exactly, Schefferdecker is supposed to have done is never specified. Still, something must be done about it:

I have given you the information which I know to be a fact, and it remains with you to see that the enemy officer is interned and not allowed to enjoy the same privileges as the parents of the boys from that district who are now at the front fighting; doubtless many more would enlist if it were not for the fact that so many Germans are permitted to profit by the freedom we are fighting for.

This seems to be the heart of the matter: this Schefferdecker may not have actually done anything wrong, but he is a German and the fact that he remains free is an affront, and it’s no wonder that new recruits for the AIF are drying up. This month in fact saw the lowest recruitment figures for the war to date — only 1500 across the entire country — so perhaps the writer was getting at some confluence of fears to do with the war draining manpower away and leaving the nation defenceless. Or else they had very cannily happened on a theme which was already creating much official alarm and despondency down in Melbourne, especially after the failure of the bitterly divisive second conscription plebiscite in December 1917.

Either way, it’s doubtful whether the Minister ever read the letter; but the Director of Military Intelligence, Major Piesse, did, and he passed it on to his naval counterpart, Lieutenant Commander Latham, together with a cover letter, NAA: MP1049/1, 1918/066, page 870. There Piesse states that the Military Commandant, Victoria, has been directed to investigate whether Schefferdecker can have had any connection with the mystery aeroplanes, and to keep the Navy informed.

Piesse also notes that this is not the first time Schefferdecker has come to the attention of military intelligence. According to an August 1915 police report, the German — whose name is (correctly) given as Paul Schifferdecker, not Schefferdecker — was naturalised in early 1912 (meaning, contrary to the anonymous letter writer’s claim, that he must have been arrived in Australia no later than early 1911) in order to become a shire councillor. But rumour had it that Schifferdecker was ‘guilty of making use of disloyal utterances’ and ‘the distributing agent of any news that is spread among the Germans’. Before the war he regularly received money from his father in Germany, ‘but the general impression here is that he is a paid agent by the German government’. And he was indeed a former officer in the German army, a lieutenant (and given that Germany had conscription, it could have been added that this means little in itself). The police had visited Schifferdecker’s farm and found no wireless apparatus, nor any weapons or pigeons.

However, Piesse added that more recently Schefferdecker/Schifferdecker had aroused suspicions over his correspondence, and just a few months ago been prosecuted under regulation 19B of the War Precautions Act. This does sound suspicious, but this regulation related to mail offences, and it might only mean he had done something like trying to send a letter back home to Germany (which was allowed only if sent via the censor). Latham has commented on the bottom of Piesse’s letter that ‘I do not see that we can do more than suggest obtaining an updated police report’.

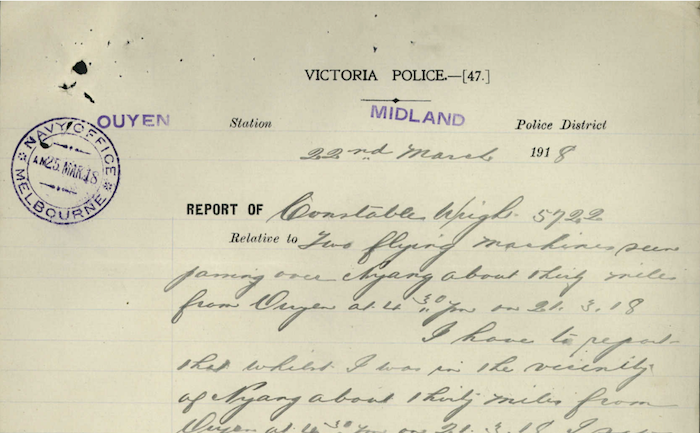

In my article I use this anonymous letter as an example of the way that the aeroplane scare was linked to suspicion of subversion by disloyal German immigrants, already well-entrenched by this point in the war. I might also have commented that the fact that it was sent only a couple of days after the Nyang sighting was made public shows how this link — not present in Constable Wright’s own report, nor in the press accounts — was made very early on in the panic. But I didn’t.

That’s the end of Nyang Week, but the post-blogging will continue!

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

Pingback: Wednesday, 3 April 1918 – Airminded