Some photos I took while in Perth for the AAEH. I didn’t have a lot of time for sightseeing in Perth itself; apart from a bit of a wander through the CBD and a look at the Museum of Western Australia (disappointing after seeing the Fremantle branches), my main outing was to Kings Park. This is a huge park, apparently the largest inner city park in the world and the oldest in Australia, and combines a botanical garden, natural bush, and a war memorial precinct (the bit I was mainly interested to see).

I found Perth to be quite an attractive city (with a sensible and functioning public transport system!). A lot of that has to do with the Swan River, which runs through the middle (and has dolphins and black swans), but the built environment plays its part too. (The University of Western Australia, where the conference was mostly held, is all limestone and Romanesque, very pretty.) Hopefully the ongoing mining boom won’t spoil things.

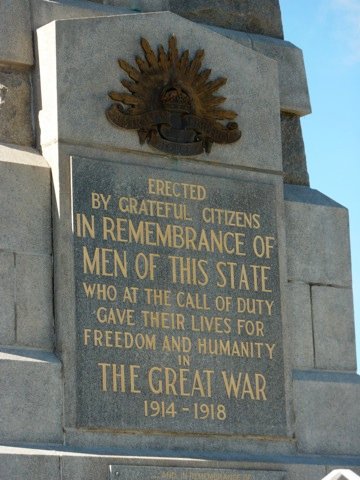

Western Australia’s State War Memorial sits on the edge of Mount Eliza, overlooking both the city and the river. The site was chosen in part because it was reminiscent of the bluffs at Anzac Cove.

Like the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne, the War Memorial was built to commemorate the First World War. But unlike the Shrine, its inscription dedicates it to those ‘who at the call of duty gave their lives’, not those who served:

ERECTED

BY GRATEFUL CITIZENS

IN REMEMBRANCE OF

MEN OF THIS STATE

WHO AT THE CALL OF DUTY

GAVE THEIR LIVES FOR

FREEDOM AND HUMANITY

IN

THE GREAT WAR

1914-1918

That’s unusual for Australian war memorials from this period, I think, thanks to the all-volunteer nature of the AIF. I wonder if this difference had something to do with Western Australia’s enthusiasm for conscription: it was one of only two states to vote yes in both plebiscites, each time by easily the biggest margins (70% and 64%). But given that conscription did not come into effect, it’s hard to see why Western Australians would have decided to slight their volunteers.

But perhaps the reason was financial: underneath the Cenotaph is a crypt with the names of the war dead engraved upon the wall. Listing all who served would have increased the cost considerably.

After doing some research — i.e., reading the relevant section of Ken Inglis’s Sacred Places — it seems the answer might that both conscription and finance were at work, but not in a straightforward way. The Cenotaph, which was completed in 1929, was funded entirely by public subscription, with no contribution from the state government. The Labor premier of the day, Phillip Collier, had been an anti-conscriptionist during the war, and would not now contribute funds to the memorial unless it was something which was of practical benefit to the community (e.g. a hospital). Then again, the preceding conservative coalition government under James Mitchell (who seems not to be strongly associated with either side in the conscription debate) had also refused to contribute funds to the memorial. Since the public was in fact not generous in its financial support, this led the memorial committee to adopt a design on a more modest scale than in some of the other states. But whether this had any effect on the stated purpose of the memorial, Inglis doesn’t say, and I’m only guessing that it did.

The Flame of Remembrance, looking away from the Cenotaph.

There are a number of other war memorials in Kings Park.

This one is is also from the First World War. It was dedicated in 1921 to the ‘glorious dead’ officers and men of the 10th Light Horse:

THE

GLORIOUS

DEAD

10TH LIGHT HORSE

REGIMENT

Another memorial of the First World War, but an unusual one: the Jewish War Memorial for WA’s Jewish war dead. It was dedicated in 1920 by General Sir John Monash. He was the obvious choice: not only was he Australia’s most outstanding military leader of the war; he was also Jewish.

I won’t attempt to transcribe this! But the English panel says:

TO THE MEMORY OF THE

SOLDIERS OF THE JEWISH FAITH

BELONGING TO THIS STATE WHO

WERE KILLED IN ACTION OR

WHO DIED OF WOUNDS ON THE

BATTLEFIELDS OF GALLIPOLI, FRANCE,

BELGIUM AND PALESTINE IN THE

GREAT WAR

1914-1918

ERECTED BY THE MEMBERS OF

THE PERTH HEBREW CONGREGATION

One of the more unusual war memorials I’ve come across — though it’s not really a memorial, but a donation box for ‘contributions towards upkeep sailors and soldiers avenues in this park’. It looks something like a rocket, and indeed it was originally a projectile:

SHELLS FROM

HMS QUEEN ELIZABETH

PRESENT AUGUST 1920

TO

KING’S PARK, PERTH, WA

BY

EARL BEATTY

ADMIRAL OF THE BRITISH GRAND FLEET, 1916-1919

So the big shell on top would be a 15-inch shell, the bottom ones 6-inch shells, and the ones in the middle 3-inch shells. (Presumably no longer live!) Queen Elizabeth was commissioned in January 1915; one of her first missions was to cover the Australians and New Zealanders landing at Anzac Cove. Shells like these would have been flying over their heads.

A couple of more recent memorials now. This one commemorates the Western Australians who were killed or injured in the Bali bombings in 2002. (Compare with the Bali memorial in London.)

It probably doesn’t look like much but I did find it quite effective, as it is quite an intimate and contemplative place here looking over the Swan. According to the architects of the memorial, it has an astronomical alignment which is best appreciated at dawn on 12 October — the anniversary of the bombings.

Unfortunately, I didn’t think that this memorial worked as well. It’s for the 2/16th Battalion, which was raised in Perth in 1940, fought in Syria against the Vichy French the following year, and then spent the rest of the war fighting the Japanese in New Guinea and Borneo, including a spell in the most desperate part of the Kokoda campaign. (At the end of its service in New Guinea, 2/16th had only 53 effectives, out of something like seven or eight hundred men at nominal strength.) The memorial does not seem to do justice to this impressive record.

Back to the old stuff, then. Though that’s a disrespectful way to introduce a memorial to Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom, Empress of India, and Ruler of Quite a Few Other Places.

By the time this statue was erected, in 1902 (a year after her death), there can’t have been many cities of any size in the Empire without a Victoria and her imperious gaze.

And lastly, Kings Park’s first war memorial, from Australia’s first war — the Boer War. The foundation stone was laid in 1901, when the war was still going, by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York who had been to Melbourne to open Australia’s first parliament. The plaque lists all those men from the West Australian contingent who died in service in South Africa; another plaque adds the names of those who survived the Boer War but not the First World War. There are no explanations or justifications given for these deaths, no mourning either; they are just facts. But the rest of the memorial is quite triumphalist: most obviously, the gun in front is a Krupp captured at Bothaville.

The other sides of the monument are covered with friezes depicting scenes from the war, which is not something you see with memorials to later wars; it reminds me of the Aurelian Column in Rome. Here is a 4.7-inch gun of the Naval Brigade in action at Ladysmith.

The caption for this one reads:

DISPERSING TRAIN WRECKERS

MOUNTED AUSTRALIANS DISPERSING BOERS

WHO HAVE WRECKED A TRAIN NEAR BLOEMFONTEIN

You can see one of the Boers cowering in the lower left; on the right it looks like another has been flung to the ground, possibly dead.

But best of all is the statue on top, showing a brave and noble digger (complete with slouch hat) standing guard over a presumably wounded tommy, just as Australia itself was helping defend Britain’s interests. In many ways the Anzac myth started in South Africa, not Gallipoli.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.