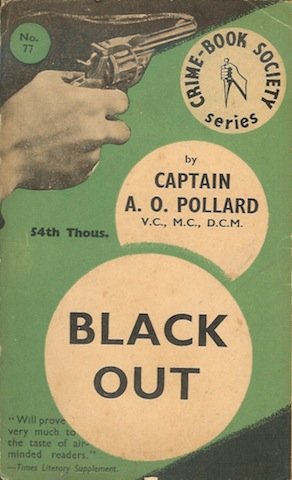

You shouldn't judge a book by its cover, but you can often pick up a few interesting things about it. Here we have number 77 in the Crime-Book Society series, Black Out by Captain A. O. Pollard. Fifty-four thousand copies have been sold (or at least printed), which makes it a fairly successful title. It's not clear from the photo, but I can tell you it's a paperback and therefore cheap, which helps. The author clearly has a distinguished military background: Victoria Crosses generally weren't handed out for no reason. And, most intriguingly, the Times Literary Supplement is quoted as saying that Black Out 'Will prove very much to the taste of air-minded readers'.

And so it did. This is so even though Pollard's main claim to fame was as a soldier, not an airman: he enlisted in 1914 as a private, ended up a captain, and in addition to the VC won the MC and bar and the DCM. The Oxford DNB compares his autobiography, Fire-eater: The Memoirs of a VC (1932), to Jünger's Storm of Steel for its evocation of the joy of combat. Starting in the 1930s he wrote dozens of crime and spy thrillers, some of which were reviewed in the TLS (though I can't actually find the one quoted on the cover of Black Out seen above).

After the failure of his first marriage in 1924, Pollard joined the RAF and became a pilot. He served for less than three years, but he seems to have made more use of his flying experience in his writing than his fighting experience. He reviewed aviation-themed books for the TLS. He wrote several non-fiction books on aviation (e.g. The Royal Air Force, 1934; Epic Deeds of the RAF, 1940; Bombers over the Reich, 1941). And it seems that many, perhaps most of his thrillers involved aviation in some way. Some of the titles suggest this: The Death Flight, The Phantom 'Plane, Murder in the Air, Air Reprisal (which I think is a knock-out blow novel). Available plot summaries of others confirm this: for example, The Murder Germ features 'an excellent fight in mid-air between the hero and a homicidal maniac' (TLS, 16 October 1937), while The Secret Formula has 'Aeroplane fights and crashes' (TLS, 29 April 1939). His protagonists were often RAF or ex-RAF types: Pirdale Island opens with a flying-officer being drummed out of the service, who then gets involved in a scheme to steal the plans of a new robot aeroplane; Pollard had at least two recurring heroes who were 'air detectives', Wing-Commander Stanley Leach and, post-war, David Wilshaw. (Biggles would be an obvious comparison, but Pollard was writing before W. E. Johns, so perhaps inspiration went the other way.)

Pollard's Black Out follows this airminded formula. (Spoilers follow, if anyone really cares!) The backdrop is a little unusual, however. As the title suggests, it involves air-raid precautions, which were an increasingly prominent part of life by the time the book came out in 1938. (Which was even more the case for ARP Spy, published in 1940.) It starts during an ARP exercise, with a flight of RAF bombers flying in restricted airspace above a blacked-out area. One of the pilots, Flying-Officer Barney Leighton, thinks that mucking about in fog and complete darkness is a mug's game, and decides to 'accidentally' lose touch with his formation so that he can return to the aerodrome and a nice hot mug of cocoa. But he collides with another, unseen aeroplane and is forced to crash land in the grounds of a country mansion. He and his rear-gunner parachute to safety, but the latter is murdered while stumbling around in the dark. Leighton finds the body and the murder weapon, which unfortunately opens himself up to blackmail by the real murderers who he encounters soon after. He realises he's up against it, and he is partly to blame, but he wants to put things right. Who are these men? Why did they kill his gunner? And whose aeroplane did he bump into?

It happens that the mansion belongs to Mrs Browne-Jervoise, a wealthy widow who is well known for her involvement in a pacifist group called the League of International Harmony. And she has some talent as an orator; she is first seen haranguing a League meeting:

"I tell you my friends, that the Government is deliberately preparing for war. All this talk of rearmament, of laying in stocks of food and munitions, of training the people in Air Raid Precautions -- what else can it mean but war? Why otherwise would they spend hundreds of millions of pounds -- money wrung from you and your comrades by unjust measures and crushing taxation -- if it is not to engage in another Armageddon?

"And don't forget for one moment -- let it be written in words of fire so that all shall learn, mark, read and inwardly digest -- most of the Cabinet hold enormous stocks in munitions concerns, and though you and your wives and children may be mutilated, massacred and tortured in tens of thousands of casualties, the capitalist overlords who strut in Whitehall will emerge from the ashes of civilization glutted with riches."1

Browne-Jervoise clearly has communist sympathies, despite her wealth. And despite her late husband having been an air vice-marshal, she hates the RAF, as is shown by her remarks when she hears Leighton's flight droning overhead:

"The playthings of the warlords!" she cried. "Unless they are destroyed root and crop the day is not far distant when they will be raining death on innocent babes and sucklings."2

Fiery stuff. But we are not meant to sympathise with Browne-Jervoise's sentiments or the League. Her own (half-)brother-in-law, a disabled veteran soldier named Stephen Wrightson, is immediately seen to be poking fun at her lack of education to her own daughter, Phyllis (naturally the novel's love interest), who is embarrassed thereby. And the omniscient narrator tells us that the League was

Formed originally so that a few extremists with pacifist tendencies might air their views to sympathetic listeners, it had now become a vast semi-political faction which interfered in every project inaugurated for National Defence and openly denounced the members of the Government as traitors to the best interests of the people.3

Later, Air Vice-Marshal Sir Humphrey Witherspon, Director-General of Personnel at the Air Ministry, says of the League:

like most peace organizations it is thoroughly militant and aggressive. You know the sort of thing -- disarm to the last gun and then issue an ultimatum to the most heavily armed nation in the world.

"At present the principal bugbear of the League of International Harmony is the Air Raid Precautions scheme. There's a woman named Mrs. Browne-Jervois, their president, who's going up and down the country raging like a wild -- er -- bull, and calling on all and sundry to swear to die in their homes like rates before they will accept a few simple regulations devised solely for their safety.4

Obviously Sir Humphrey (and presumably Pollard himself) didn't have much time for pacifists. But whether he fairly described the aims of pacifist organisations or not, his perceptions probably seemed plausible enough to some of the people who read it. And some pacifist groups did oppose ARP as preparations for (and so increasing the likelihood of) war, such as the Peace Pledge Union.

But it's not just an anti-pacifist rant; Sir Humphrey suspects that the League has been working to subvert ARP by less-than-legal means. First was a small-scale strike in a government munitions factory when someone from the Home Office came to lecture them on ARP, followed by possible arson in a Birmingham gas mask store. And this seems to be confirmed when a number of arson attacks are carried out in the town of Lyttleton during a trial black-out, at the same time as Mrs Browne-Jervois is presiding over a public League meeting being held there. Every fire brigade within thirty miles is called in to fight the fires, and at least a million pounds' worth of damage is done. Police arrested a number of men wearing 'air-raid protection-outfits' and two bodies full of bullet holes.5 The prisoners, at least some of whom were known communists, admitted to having been paid in order to sabotage ARP for revolutionary purposes. Sir Humphrey is perplexed as to the purpose: the best explanation seems to be that they hoped to discourage other boroughs from participating in ARP, lest the same thing should happen to them.

But in fact the Third International was not behind it all. Nor -- despite a red herring involving Italian immigrants, charmingly referred to more than once as 'dagoes' and 'icecreamios', the latter insult a new one on me -- was it a foreign power. It turns out that Wrightson, Browne-Jervois' half-brother-in-law, was the one using the League as cover for the nefarious arson attacks. But why? This was perhaps the most interesting part of the book. As I noted above, Wrightson was a disabled veteran of the Great War, having joined up in 1914 and had his leg amputated after Passchendaele, and this is key to his motivations. Because of his service and his suffering, and the loss of his hopes for the future, his mind has been twisted.

"Out of the chaos through which I passed emerged a fixed resolve. I swore a mighty oath that if I ever got well again somehow I would avenge myself on the system of society that had allowed such suffering to humanity. He, he, he!''6

(Yes, it does actually say, 'He, he, he!' -- this is apparently frenzied laughter.) He used his half-brother's widow's money to recruit American gangsters, and with them began 'upsetting the Government's preparations for the next war'.7

By stopping war I shall save millions of men, women and children from suffering the agonies that I've suffered. Don't you understand? I owe it to humanity!"8

His interlocutor realises that Wrightson is insane, but tries one last time to get through to him.

Wrightson's face wrinkled in despair.

"There you go again -- atrocities. They're not atrocities. If only I can make the people realize what an air raid will be like, they will rise unanimously to prevent the country being plunged into war."

He sank into a chair and tears started in his eyes.

"It's so hard to make you understand; it's so hard to make anyone understand. I ..."

His voice died to a whisper and he buried his face in his hands.9

This portrayal might seem sympathetic, but it's at this moment of vulnerability that one of our RAF heroes launches himself at the damaged veteran and grapples him to the ground. More stuff happens, but rest assured that the madman gets what he deserves in the end, Leighton gets his name cleared and the girl, and (presumably) Britain's preparations for war continue unabated. Still, coming from the pen of such a highly decorated veteran Wrightson is a surprising and interesting villain. Combined with the unusual use of resistance to air-raid precautions as a plot device this makes Black Out an unexpectedly interesting read.

Oh, and it also has an amphibian flying-boat, an 'Aston Arrow' (something like a Defiant) and a two-man autogyro bomber. So it has all that going for it too.

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available at http://airminded.org/copyright/.

JDK

You swayed me into needing to read it with the last para...

As far as I recall, there's no mention of Pollard in John's biography; and there was a lot of aerial-thriller-writing in the inter war period, so while 'possible influence' we'd need some evidence to upgrade. We also know John's created Biggles specifically as a counterblast to the US pulp-magazine air heroes of the great war - oh, and to fill magazine space!

I have Pollard's The Boy's Romance of Aviation and it certainly has some romantic chunks. A '...shark-infested Timor Sea...' being one highlight.

Nicholas Waller

Mind you, not all 1930s-era communist-sympathising types from pacifist backgrounds automatically went on to hate the RAF. My father had been a CP member in 1938 and 1939 - I still have his party cards - and had even travelled to Moscow and Leningrad in August 1939 with £21 given to him on his 21st birthday; and his father, a serious Quaker, had been a conchie banged up in Wormwood Scrubs for part of WW1.

But in 1940 my father joined the army, then transferred to the RAF in 1941, became a flying instructor in Canada and a Coastal Command Liberator pilot at RAF Leuchars, became a respectable airline pilot and ended life in 2004 as a Lib Dem (unless that was just a cover and he waged a ceaseless struggle against our capitalist-imperialist overlords without my noticing...)

Brett Holman

Post authorJDK:

I'm thinking more of the 'Biggles, air detective' type stuff that Johns turned to after running out of war stories, rather than Biggles himself. The few references to Pollard I've seen categorise him as a crime writer, when it looks like he was a aviation writer too, so I can imagine any influence he had has been forgotten. But I'm no Johns scholar so I'm not putting any money on it!

Nicholas:

You said it yourself: he was a card-carrying communist who was in Moscow in 1939, then joined the British armed forces and became a respectable member of society. Obvious sleeper agent.

JDK

Ah, fair comment, Brett. I think postwar crime / spy stories are a separate genre to the inter-war efforts as they in turn are from the pre-Great War ones. But certainly a noteworthy correspondence even if a link is unproven.